Services received for a potential population in need of palliative care

Understanding who currently receives and needs palliative care is crucial to service planning and design. Although there have been research studies estimating a population in need of palliative care, there is currently no nationally consistent dataset or methodology to establish either need or unmet need in Australia.

This section aims to address some of these data gaps by presenting a holistic picture of the care provided to a population in need. This is derived from studies identifying conditions that often generated a need for palliative care (see Populations and Appendix B for further details).

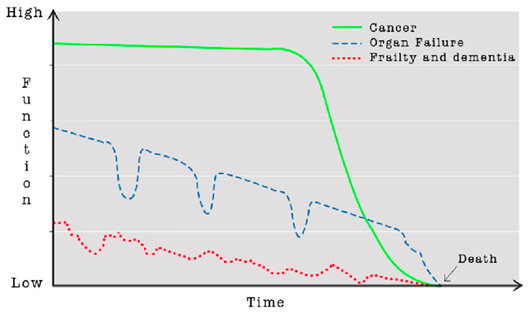

A key focus is examining service provision by the 3 broad end-of-life disease trajectories (Figure 4.1). These disease trajectories provide a conceptual overview of disease progression and specific clinical approaches at the end of life and are categorised into 3 groups – malignant neoplasms (cancer), organ failure (heart failure, COPD, liver failure), and frailty (dementia, Parkinson’s disease, senility; Seow et al 2017).

Figure 4.1: End-of-life trajectories

Source: Teggi, Diana. (2018). Unexpected death in ill old age: An analysis of disadvantaged dying in the English old population. Social Science & Medicine. 217. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.09.048.

A palliative approach to care can benefit anyone with a life-limiting illness and so is necessarily varied in where it is delivered and by whom. For example, it can be provided in the community by GPs and disease-specific specialists and in hospitals by almost any speciality team. It is often appropriate to introduce a palliative approach to care from the time it is recognised that a patient has a progressive, life-limiting condition (Palliative Care Therapeutic Guidelines).

Not all people with life-limiting conditions require specialist palliative care services, however, the care of patients with complex problems (as described in Chapter 3) may benefit from involvement of a specialist palliative care team, in collaboration with the patient’s usual healthcare providers (who already have an established relationship with the patient). In particular, integrating palliative care services with the primary specialist physician (e.g. cardiologist, nephrologist, respiratory physician), specialist palliative care team and GP, has shown to achieve better outcomes (Palliative Care Therapeutic Guidelines). Palliative care specialists have a key role to play in building the capacity of other providers to adopt a palliative approach to their patients’ care (DoHA 2018). This is particularly important given the traditional medical treatment model (curative and aggressive treatment initially and then palliative care at the end of life) is still largely used for people with life-limiting conditions (Rome 2011).

Identifying when palliative care has been provided and by whom remains a significant challenge and key data gap. Current available data is limited to services provided by palliative care specialists that are claimed under MBS item numbers or identified through hospital activity (see Receipt of care for further details). However, a large volume of care occurs outside of specialised palliative care settings, such as in primary care and residential aged care, which are not claimed specifically as a palliative-care related service and therefore not captured in existing data collections. Although there have been research studies estimating a population in need of palliative care, there is currently no nationally consistent collection of data or methodology to establish either need or unmet need for palliative care in Australia.

This chapter aims to address some of these data gaps by presenting a more holistic picture of the care provided to a population in need of palliative care. It focuses on the 109,059 people aged 40+ who died from 10 selected underlying causes of death in 2019–20, derived from studies that have identified conditions that most often generated a need for palliative care (see Study Populations and Appendix B for further details). It explores the types of specialist and other relevant services received (see Service Use) in the last year of life, who provided these services, when these services were initiated or ceased, and whether consultations with specialist palliative care physicians occurred alongside other disease-specific specialists for a population in need of palliative care.

Note, we do not know if the services provided by non-palliative care health professionals have adopted a palliative approach to care in consultations with patients or the reasons for the consultation, as this is not identified in existing administrative data. However, the information presented in this chapter is designed to provide an overview of care delivered across healthcare settings or by non-palliative care specialists, to complement the information provided in Chapter 3 on provision of specialist palliative care.

Note that the population in need of palliative care is derived from studies that have identified conditions that most often generated a need for palliative care. Therefore, it cannot be assumed that all people who died from these conditions required specialist palliative care or did not receive appropriate palliative care from other health professionals (outside of specialist palliative care). This should be considered when interpreting the results in this chapter.