Who uses violence?

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

Key findings

- Based on the 2021–22 PSS, women were more likely to have experienced physical and/or sexual violence since the age of 15 by a known person (35% or 3.5 million) than a stranger (11% or 1.1 million).

- Based on the 2021–22 PSS, men were more likely to experience violence from a stranger (30% or 2.9 million) than from a known person (25% or 2.4 million).

- Based on the 2021–22 PSS, 20% (2 million) of women have experienced sexual violence by a male they know since the age of 15, while 6.1% have experienced it from a male stranger.

- Around 1 in 4 (25%) offenders in 2022–23 were proceeded against by police for at least one family and domestic violence related offence.

While experiences of family and domestic violence, intimate partner violence and sexual violence are diverse, these are forms of violence that are more commonly experienced by some people – such as women and children – than others. These are also forms of violence more likely to be perpetrated by men than by women.

Much of the focus of national reporting has been on victim-survivors, building the evidence base about perpetrators and people who use violence can help ensure that policies and programs are better designed to prevent violence before it occurs, and stop it from reoccurring (see Policy and international context).

This page highlights what is known about those who use family, domestic and sexual violence (FDSV) and some of the challenges in identifying and reporting on this group.

What do we know?

Currently, national reporting focuses on the risk factors, experiences, responses, impacts and outcomes for people who have had violence used against them, either directly or indirectly. While there is a growing body of research that points to the typical risk factors for perpetration – the individual, interpersonal, community and societal factors that make perpetration more likely – data on the full extent of violence perpetration in Australia is limited (Flood and Dembele 2021; Costa et al. 2015; Jewkes, 2012; Tharp et al. 2012). For more information about risk factors, see Factors associated with FDSV.

In many instances, data about people who use violence are collected from victim-survivors. This occurs both in surveys (for example, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Personal Safety Survey (PSS)) and in service contexts (for example, in hospitals). Because the information is collected from the victim-survivor, there can be challenges in using these data to both build a profile of those who use FDSV and understand the patterns of perpetration.

How do we write about people who use violence?

Violence is a broad term, often used to encompass a wide range of behaviours and definitions that vary according to different legislation and practices (see What is FDSV?). Different terms – such as perpetrators or offenders – may be used to describe people who use FDSV, depending on the context in which the violence occurs or how the information is collected (Box 1).

People who use violence is an inclusive term, which encompasses all those who use violence against others. The term ‘people who use violence’ applies for all forms of family, domestic and sexual violence, and can be used to describe any person, regardless of their age, sex or other characteristics. ‘People who use violence’ is the preferred term for children and adolescents (aged 18 years and under) who use violence and people in some groups or communities, where other terms, such as ‘perpetrator’ may not always be appropriate.

Perpetrator is a term used to describe adults aged 18 years and over, who use violence. Perpetrators can use any form of violence, and this violence can occur within, or outside, a family and domestic context. Perpetrator is the most common term used by data sources throughout the AIHW FDSV reporting when referring to adults who use violence.

Offender is the term used when violence has been deemed to be a criminal offence. An offender is a person aged 10 years or over who is proceeded against and recorded by police for one or more criminal offences. A person who has been proceeded against by police for family and domestic violence related offences may be referred to as an ‘FDV offender’. People aged 10–17 may be referred to as ‘youth offenders’.

Defendant is a term used to describe someone who has been charged with a criminal offence. The term defendant is often used to describe a person within the criminal court systems.

In AIHW FDSV reporting, the term used to describe people who use violence will vary depending on the data source used. For more information about each specific data source, see Data sources and technical notes.

What data are available to report on people who use violence?

Data on people who use violence are often collected from those who have experienced violence, either through surveys, or as part of an interaction with a service provider. These data can be supplemented with police data, courts data, coronial data, or data from specialist perpetrator services, which work directly with those who use violence.

- ABS Criminal Courts

- ABS Personal Safety Survey

- ABS Recorded Crime – Victims

- ABS Recorded Crime – Offenders

- AIC Australian Sexual Offence Statistical (ASOS) collection

- AIC National Homicide Monitoring Program

- AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database

For more information about these data sources, please see Data sources and technical notes.

Ten to Men: The Australian Longitudinal Study on Male Health is Australia’s first national longitudinal study that focuses exclusively on male health and wellbeing. Further analysis of the Ten to Men study can provide insights into the health and wellbeing of men who have experienced and/or perpetrated intimate partner violence. For more information about the Ten to Men study, please see the Data sources and technical notes.

Reframing the narrative around violence perpetration

Most of the key statistics used to report on FDSV are derived from victim-survivor experiences. For example, the ABS PSS tells us the proportion of people in Australia who have experienced violence by a family member since the age of 15. With these data, we can say how many people have experienced violence by a certain type of person, however, we cannot generalise the findings to perpetrators more broadly. Data from the ABS PSS cannot show us how many people in Australia have used family, domestic or sexual violence. This means that the way we report on violence in Australia can sometimes be limited in how it portrays the people who use violence against others.

Shifting the focus onto perpetrators

'It is critical to realise from a policy and community attitude level that violence is a problem for victims, but it’s not a victim’s problem. We need to be talking about perpetration/perpetrators a lot more. They are still hidden in the narrative and understanding about where the responsibility lies to end all forms of family, domestic, and sexual violence.'

Lula

These challenges are ongoing, and data about people who use violence remains a key data gap (see Key information gaps and development activities). A growing body of research aims to address these information gaps. In 2022, a State of Knowledge Report on Violence Perpetration was published by the Queensland University of Technology. The report summarises key research on perpetration and identifies potential areas for data improvement (Flood et al. 2022).

For more information about how the AIHW uses data in FDSV reporting, see How are national data used to answer questions about FDSV?.

What do the data tell us?

The ABS PSS captures information about perpetrators from those who have experienced violence (Box 2).

The PSS defines a perpetrator as a person responsible for any acts of violence or abuse, as identified by the person who the acts were directed against. Relationship to perpetrator refers to the relationship of the perpetrator to the person at the time of the interview, as perceived by the person who the violence or abuse was directed against (ABS 2023).

-

29%

of people in 2021–22 had experienced violence from a known person, while 17% experienced violence from a stranger

Source: ABS Personal Safety Survey

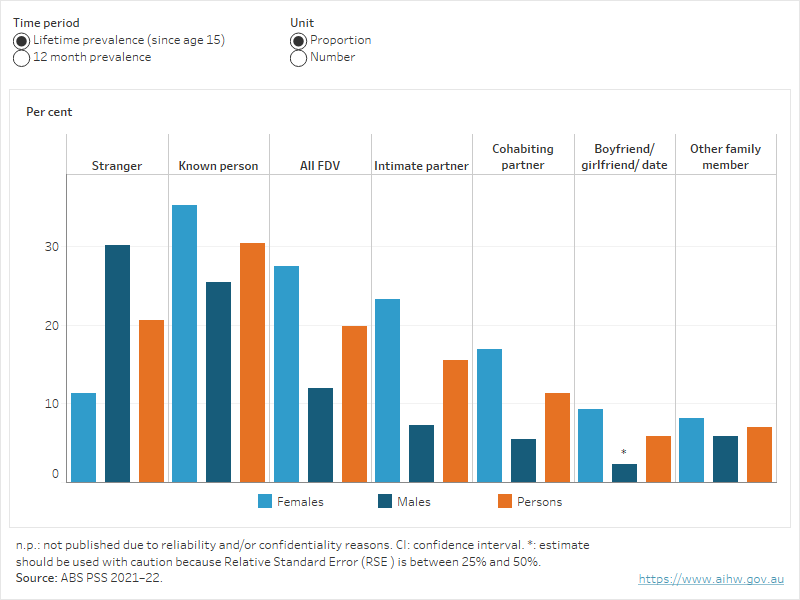

In the 2021–22 PSS, some information about perpetrators was collected about physical and/or sexual violence experienced by women and men since the age of 15. Based on the 2021–22 PSS:

- more people have experienced violence by a male perpetrator (38% or 7.5 million people aged 18 years and over) than by a female perpetrator (11% or 2.2 million)

- women were more likely to have experienced physical and/or sexual violence since the age of 15 by a known person (35% or 3.5 million) than a stranger (11% or 1.1 million)

- men were more likely to experience violence from a stranger (30% or 2.9 million) than from a known person (25% or 2.4 million) (Figure 1; ABS 2023).

Figure 1: Prevalence of violence, by relationship with perpetrator and sex of victim, 2021–22

The interactive visualisation shows the number and proportion of people who have experienced violence, by the relationship to perpetrator. The perpetrator categories are: stranger, known person, all FDV, intimate partner, cohabiting partner, boyfriend, girlfriend or date, and other family member.

For women, FDV was more common than violence from any other known person – more women had experienced violence from an intimate partner or family member (27% or 2.7 million women) than other known persons (17% or 1.7 million). Among men, a greater proportion had experienced violence since the age of 15 by other known persons (19% or 1.8 million) than by intimate partners or family members (12% or 1.1 million). Other known persons includes a wide range of people such as friends and acquaintances, employers, medical practitioners, or people who have not been specified (ABS 2023).

For more information about the violence experienced in family and intimate relationships, see Family and domestic violence and Intimate partner violence.

Sexual violence against women is often perpetrated by someone they know

-

20% of women in 2021–22 had experienced sexual violence by a male they know since the age of 15, while 6.1% had experienced it from a male stranger

Source: ABS Personal Safety Survey

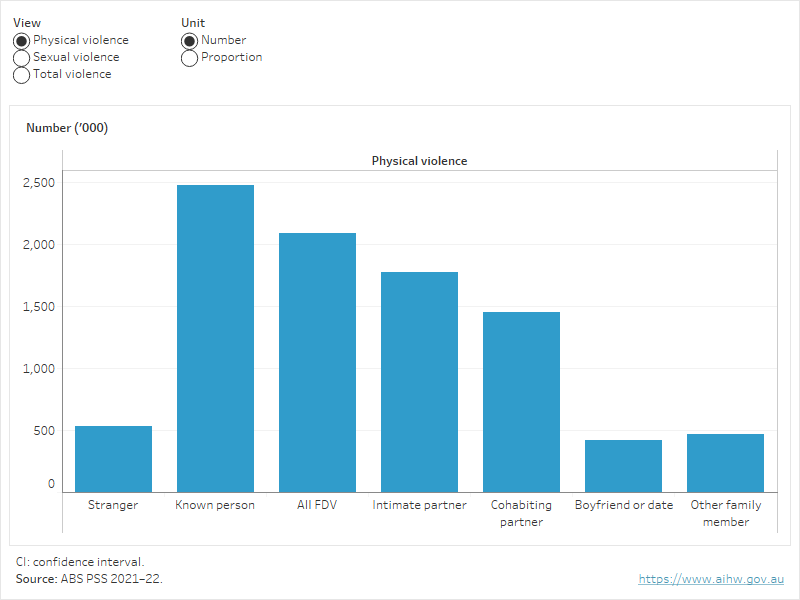

The 2021–22 PSS includes data about perpetrators of sexual violence among women, where the perpetrator was male. For women, the male perpetrators of sexual violence were more commonly a known person than a stranger:

- 20% (2 million) of women have experienced sexual violence by a male known person since the age of 15

- 6.1% (605,000) of women have experienced sexual violence from a male stranger (ABS 2023).

Around 1 in 9 (11% or 1.1 million) women have experienced sexual violence by a male intimate partner. See Sexual violence for more information about the types of sexual violence experienced.

Figure 2: Lifetime prevalence of violence against women, by relationship with male perpetrator, 2021–22

The interactive visualisation shows the number and proportion of women who have experienced physical or sexual violence perpetrated by a male, by the relationship to perpetrator. The perpetrator categories are: stranger, known person, all FDV, intimate partner, cohabiting partner, boyfriend or date, and other family member.

What are the risk factors for using violence?

Risk and protective factors for violence can be at the individual, family, community or broader societal-level. These factors are discussed in more detail in Factors associated with FDSV.

For people who use violence, research shows that common risk factors include substance abuse, growing up in a violent home, witnessing violence at an early age, attitudes that are supportive of gender inequality, and access to firearms (Clare et al. 2021). Gendered factors also play a role in driving violence, as they create the underlying conditions for violence to occur (Our Watch 2022).

Some abusive and harmful behaviours can also be risk factors for further violence. For example, the use of controlling behaviours to maintain power over another – also referred to as coercive control – is often cited as a risk factor for intimate partner homicide (ANROWS 2021).

In most cases, the data available can only be used to show associations between risk factors and FDSV. These data cannot show that the risk factor caused the FDSV to occur. Looking at characteristics of perpetrators when violence has occurred can reveal some patterns of behaviour and identify stages for possible intervention.

Across population groups, known risk factors for FDSV can intersect with other forms of disadvantage. For example, among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people, the ongoing impacts of colonisation, racism and intergenerational trauma intersect with gendered drivers and other known risk factors to contribute to FDSV (DSS 2022). These are discussed further in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Attitudes supportive of violence against women

Attitudes that tolerate, accept or justify violence against women have been associated with perpetration of this violence. In addition, attitudes that deny gender inequality and support rigid gender roles have been identified as the strongest predictors of attitudes that condone violence against women (Gracia et al 2020).

More detailed information about community attitudes towards violence are discussed in Community attitudes.

Alcohol and drug use

Problematic alcohol use is consistently and strongly associated with FDV (Foran & O’Leary 2008). IPV that occurs when either one or both partners consumes alcohol is particularly harmful due to more severe levels of violence perpetration and a greater likelihood of physical injury (Curtis et al. 2019; Graham et al. 2011; Laslett et al. 2010).

The link between alcohol and drug use, and violence perpetration can be examined using data from surveys or police records (Box 3).

In 2014, the National Drug Law Enforcement Research Fund (NDLERF) funded the Alcohol/Drug-Involved Family Violence in Australia (ADIVA) project for 2 years. The project sought to provide an overview of family violence in Australia, with a focus on alcohol and other drug-related violence. The 2 arms of the project were to conduct:

- an Australia-wide survey, focusing on alcohol and other drug use

- retrospective analyses of police offence data.

The study involved an online panel survey with a final sample of 5,118 respondents, comprised of 2,450 males (48%) and 2,652 (52%) females. The ADIVA project uses the following definitions:

- FDV can include physical, psychological, sexual, and/or emotional abuse; range from mild threats to severe abusive acts; and occur on a one-time only individual basis or can be insidious abuse that occurs over an extended period of time

- IPV incidents include any instance of violence where the relationship between the parties is of a romantic or spousal nature (for example, husband, wife, ex-spouse, de facto partner)

- Family violence (FV) incidents include any incident of violence involving other family members (for example, mother, father, sibling etc)

- Heavy episodic drinking/heavy drinking refers to the consumption of 6 or more drinks on one occasion at least once in the past 12 months.

The data can only be used to look at the involvement of alcohol and drugs in the incident of violence, rather than specifically at the role they played in the perpetration of violence.

More information can be found in the Alcohol/Drug-Involved Family Violence in Australia research reports on the Australian Institute of Criminology website.

Further research undertaken in 2018 using data from the Alcohol/Drug-Involved Family Violence in Australia (ADIVA) project described in Box 2 shows:

- almost 2 in 5 (38%) respondents who experienced IPV and 28% of those who experienced family violence reported engaging in heavy episodic drinking within the past 12 months

- heavy drinking was found to be associated with increased level of coercive controlling behaviour – perpetrators of coercive control were more likely to be current drinkers

- while drug use was only involved in a small minority of cases, it appeared to be associated with increased likelihood of experiencing FDV. Overall, 1 in 9 (11%) incidents were illicit drug-related (Mayshak et al 2018).

In 2022, additional analysis was undertaken using police data obtained through the ADIVA project. The research found that between 24% and 54% of FDV incidents reported to police were classified as alcohol-related. Where victim and offender data were available, offenders were significantly more likely to be alcohol-affected than victims (Mayshak et al 2022).

Drug Use Monitoring

The AIC Drug Use Monitoring in Australia (DUMA) program is the nation’s longest running ongoing survey of police detainees across the country (Box 4).

The AIC DUMA collects alcohol and drug use and criminal justice information from police detainees at watch houses and police stations across Australia.

DUMA comprises 2 core components:

- a self-report survey on drug use, criminal justice history and demographic information

- voluntary urinalysis, which provides an objective measure for corroborating reported recent drug use.

More information can be found at Drug Use on the AIC website.

In 2020, the AIC conducted a study into the relationship between methamphetamine dependence and domestic violence among 351 male police detainees interviewed as part of the DUMA program. The study found:

- detainees who were dependent on methamphetamine reported high rates of domestic violence

- detainees who were dependent on methamphetamine were significantly more likely to have been violent towards an intimate partner in the previous 12 months than detainees who used methamphetamine but were not dependent

- detainees who had attitudes that justified domestic violence were more likely than other detainees to report having been violent towards an intimate partner in the previous 12 months (Morgan and Gannoni 2020).

The results from the study show only associations, not causal links. More information about the project can be found on the AIC website, at Drug Use.

Violence perpetration can also be associated with other health-related risk factors such as acquired brain injury. A study conducted by Brain Injury Australia looked at the prevalence of brain injury among victim-survivors and perpetrators of family violence (Box 5).

A consortium led by Brain Injury Australia examined the extent and nature of brain injury among both victim-survivors and perpetrators of family violence. The study estimated the extent of family violence-related brain injury by analysing Victorian hospital data. In the study, family violence was defined as behaviour by a person towards a family member if that behaviour was:

- physically or sexually abusive

- emotionally or psychologically abusive

- economically abusive

- threatening or coercive

- controlling or dominating of a family member in a way that caused a person to feel fear for their safety or wellbeing.

Acquired brain injury includes traumatic brain injury due to external force applied to the head, and non-traumatic brain injury, such as from stroke, lack of oxygen or strangulation, or poisoning. Acquired brain injury is sometimes referred to as ‘brain injury’.

The study analysed Victorian hospital data of family violence-related injuries, from July 2006 to June 2016, and included major trauma, hospital admissions and emergency department presentations. Family violence was found to be a significant cause of brain injury.

The consortium also looked at international studies on brain injury among perpetrators of family violence. Although there were few studies on this, the available evidence suggested that rates of brain injury were twice as high among perpetrators as among their matched counterparts in the general population.

Further research is required to understand the interplay between brain injury and the other factors known to influence the perpetration of family violence (Brain Injury Australia 2018).

Adverse childhood experiences

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are typically described as potentially traumatic events that can have negative lasting effects on multiple domains of functioning (e.g. health and wellbeing). ACEs can be a risk factor for male perpetration of FDSV.

A study by the University of New South Wales examined child sexual offending behaviours and attitudes and their relationship to ACEs among a weighted sample of around 1,900 Australian men. In the study, ACEs included abuse (emotional, physical and sexual), low family support, neglect, parental divorce, domestic violence, household substance abuse, household mental illness and household incarceration (Salter et al. 2023).

Around 1 in 6 (15%) respondents reported having sexual feelings towards children and around 1 in 20 (4.9%) reported having sexual feelings and offending against children (Salter et al. 2023).

The 4.9% of respondents with sexual feelings and who had sexually offended against children had approximately twice the rate of ACEs of those who did not have sexual feelings, or offending towards children. They were also more likely to report that during childhood they experienced:

- sexual abuse (6.3 times more likely to report)

- neglect (4.1 times)

- domestic violence (4 times)

- household incarceration (3.7 times)

- household mental illness (3.6 times)

- household substance abuse (3.5 times) (Salter et al. 2023).

While the study sample was selected to be nationally representative, the use of a convenience, non-probability sampling methodology limits the generalisability of the findings to the adult Australian male population.

Pathways to perpetration of domestic homicide

The AIC report, The “Pathways to intimate partner homicide” project: Key stages and events in male-perpetrated intimate partner homicide in Australia, identified three main pathways of male-perpetrated homicide of a female intimate partner by analysing 199 incidents between 1 July 2007 and 30 June 2018 for patterns in the sequence of events, and interactions and relationship dynamics preceding, and coinciding with, the homicide.

In Australia, data on domestic homicides are available from a number of sources:

- The AIC National Homicide Monitoring Program: these data include characteristics of domestic homicide incidents, such as the sex of perpetrator, relationship between victim and perpetrator, alcohol and illicit drug use, weapon use and history of domestic violence.

- The Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network (ADFVDRN): these data are based on 311 cases of intimate partner violence homicides between July 2010 and June 2018, and include information about the history of abuse within the relationship.

Key findings from these data sources are presented in Domestic homicide.

What are the responses to those who use violence?

A lot of cases of FDSV go unreported and many people who seek help or advice following an incident of violence turn to informal supports such as friends or family. Service responses represent only a limited view of what happens to those who use violence. The key areas where data are available to report on service responses to people who use violence are: police and justice, and perpetrator intervention services.

Recorded crime

-

1 in 4 offenders

in 2022-23 were proceeded against by police for at least one family and domestic violence related offence

Source: ABS Recorded Crime - Offenders

Perpetrators proceeded against by police are recorded in the ABS Recorded Crime – Offenders collection. This collection includes data for FDV-related offences, which were considered experimental prior to 2022–23. For more information about this collection, see Data sources and technical notes.

In 2022–23, 1 in 4 (25% or 88,400) recorded offenders for any offence were proceeded against by police for at least one FDV related offence. The proportion was higher for male offenders (27%) than for female offenders (21%) (ABS 2024b).

Data are also available to report on sexual assault offenders. In 2022–23, around 6,400 people had a principal offence of sexual assault recorded. This represents a rate of 28 offenders per 100,000 people (ABS 2024b).

For more information, see FDV reported to police and Sexual assault reported to police.

Sexual offending

The pilot Australian Sexual Offence Statistical (ASOS) collection (see Box 6) included data from all jurisdictions, except South Australia and Tasmania, for the period 1 July 2021 to 30 June 2022.

The Australian Sexual Offence Statistical (ASOS) collection was established by the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) to monitor the extent and nature of sexual offending through police-recorded data on sexual offences, alleged offenders and victims (Sullivan et al. 2024). The collection expands on the available data for reporting on people who use violence by also including the relationship between each offender and victim and information about the offending and victimisation histories of the alleged offenders proceeded against and the victimisation history of their victims.

The collection includes people aged 10 years and over at the time of an offence who were proceeded against for any offence identified in Division 3 (Sexual assault and related offences) of the Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification (ANZSOC). Based on the 2011 edition, sexual assault and related offences are defined as ‘acts, or intent of acts, of a sexual nature against another person, which are non-consensual or where consent is proscribed’. Emerging offences not covered by the classification were also identified using offence coding developed by the AIC (Sullivan et al. 2024).

The sexual offence categories used for reporting are:

- Penetrative or non-penetrative sexual conduct offences including rape, attempted rape, sexual intercourse without consent, sexual assault and sexually touching another person.

- Persistent sexual abuse offences where a child has been subjected to ongoing patterns of sexual abuse in which repeated instances of sexual offending are perpetrated by an offender over a period of time.

- Handling of unlawful sexual material including image-based sexual abuse (IBSA) and conduct pertaining to child sexual abuse material (CSAM).

- Conduct done to enable unlawful sexual conduct including grooming children under 16 years for a sexual offence and using a carriage service to procure a child under 16 years for sexual activity (Sullivan et al. 2024).

Findings from the ASOS collection are not directly comparable with those from the ABS Recorded crime – Offenders collection due to differences in the scope of the collections. For example, the pilot ASOS collection included data for 6 jurisdictions and also includes emerging offences not covered by the ANZSOC.

See also the Data sources and technical notes.

In 2021–22, there were more than 8,300 alleged sexual offenders proceeded against (that is, arrested, cautioned or summoned to court) by police for offences involving almost 8,500 identified victims. The sexual offending rate was 40 per 100,000 population aged 10 years and over.

Of alleged sexual offenders in 2021–22:

- Most were male (93%), with a male sexual offending rate of 76 per 100,000 population aged 10 years and over; 6.5% were female, with a female sexual offending rate of 5.1 per 100,000 population aged 10 years and over.

- The average age at their first or only police proceeding for a sexual offence was 36 years (with a median age of 34 years). The average age for male sexual offenders was similar (37 years, with a median age of 35 years), however, the average age for female sexual offenders was lower at 25 years (median age of 18 years). Most female offenders (51%) were aged 10–17 years.

- 12% (or just over 1,000) were First Nations people.

- 2 in 3 (66%) were known to the victim:

- 32% were a non-family member known to the victim

- 15% were an intimate partner

- 19% were non-intimate partner family member

- 21% were a stranger.

- More than 3 in 4 (77%) were proceeded against for penetrative or non-penetrative sexual conduct offences, 1 in 4 (24%) for handling of unlawful sexual material offences (17% for CSAM offences and 8% for IBSA offences), 8% for offences related to enabling unlawful sexual conduct and 1% for persistent sexual abuse.

- Most (88%) had no prior police proceedings for separate sexual offences in the previous nine-year reference period, however when considering any offence, more than half (56%) had previously been proceeded against for sexual and/or non-sexual offences (Sullivan et al. 2024).

Legal responses and criminal courts

Family and domestic violence protection orders are a commonly used legal response for perpetrators of violence. There are currently no national data available on the number of family and domestic violence orders in effect, however, the Report on Government Services presents national data on finalised originating applications for DVOs in the Magistrates’ Courts that were not appealed. Almost half (47% or 133,000) of civil cases finalised in the Magistrates’ Courts in 2022–23 involved finalised originating applications for DVOs (Productivity Commission 2024).

People who use violence may also have their matters appear before the criminal courts. Data are available from the ABS Criminal Courts collection to report on the number of defendants finalised for FDV offences in Australia. In 2022–23, about 99,900 defendants were ‘finalised’ for FDV offences in Australia (ABS 2024a).

More details about how the legal system responds to people who use violence can be found in Legal systems.

Perpetrator interventions

Police and courts comprise only a portion of the responses to people who use violence. FDSV is not always reported, and when it is, perpetrators are not always specified. The actions people take following FDSV are discussed further in How do people respond to FDSV?

Other responses that engage directly with those who use violence are sometimes referred to as ‘perpetrator interventions’, and include a wider range of services, such as helplines and behaviour change programs, designed to address the use of violence. Currently, data on perpetrator interventions are limited. These interventions are discussed in more detail in Specialist perpetrator interventions.

How does it vary among different groups?

Adolescent family violence

‘Adolescent family violence’ refers to the use of violence by children and young people against family members, including physical, emotional, financial, and sexual abuse. It includes a range of behaviours used to control, coerce and threaten family members. Victims can include parents and carers, siblings and intimate partners (Fitz-Gibbon et al. 2022).

Although nationally-representative data are not available on the prevalence of adolescent family violence, recent research projects highlight that adolescent males more commonly use violence against family members than adolescent females, and that mothers are most likely to be victimised (Fitz-Gibbon et al 2022).

A non-representative survey of just over 5,000 young people aged 16 to 20 in Australia, found that:

- 1 in 5 (20% or about 1,000) self-reported that they had used violence against a family member, with 23% (or about 760) of those assigned female at birth and 14% (or about 235) of those assigned male

- The most common forms of adolescent family violence (AFV) used were verbal abuse (15% or about 730), physical violence (10% or 490) and emotional/psychological abuse (5% or 245), noting that multiple forms could be recorded per person (Fitz-Gibbon et al. 2022).

Young people who experienced child abuse were 9.2 times more likely to use AFV than those who had not experienced child abuse (Fitz-Gibbon et al. 2022).

More findings from this study can be found in Children and young people.

Harmful sexual behaviour

Currently, information about how sexually violent behaviour emerges and evolves in young people is limited. Child maltreatment and FDV have been identified as contributing factors towards criminal and violent behaviour. In 2022, ANROWS published a study looking at harmful sexual behaviour among male youth in Queensland, drawing on data related to adverse childhood experiences (Box 7).

A study conducted by Ogilvie et al. (2022) examined the occurrence, nature and extent of ACEs of male youth, comparing those with convictions for sexual offences to those with convictions for non-sexual offences. ACEs are typically described as potentially traumatic events that can have negative lasting effects on multiple domains of functioning (e.g. health and wellbeing). In the study, adverse childhood experiences included emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, parental separation, exposure to domestic and family violence, family member substance abuse, family member mental health problems, and family incarceration.

Two existing and distinct datasets were used:

- administrative data from the Queensland Department of Children, Youth Justice, and Multicultural Affairs

- clinical files from Griffith Youth Forensic Service, which included assessment and treatment information.

The study found:

- Adverse childhood experiences were highly prevalent among young males who encountered the youth justice system.

- Male youth with sexual offences on average had a higher accumulated number of adverse childhood experiences, compared with non-sexual violent and non-violent offending male youth.

- Male youth with sexual offences were more likely to have experienced sexual abuse, compared with violent and non-violent offending male youth.

The findings add to a growing body of research into adverse childhood experiences and the ongoing effects. More information about the study can be found on the ANROWS website, at Adverse childhood experiences and the intergenerational transmission of domestic and family violence in young people who engage in harmful sexual behaviour and violence against women.

Women who use force

In Australia, the main focus for FDSV has been on male perpetrators who use violence. In 2020, the University of Melbourne published a body of research investigating issues relating to women who use force in the Australian context.

The research used the term ‘force’ to highlight the gender differences in the way violence and abuse is used in relationships. Women who use force are described as differing in motivation, intent and impact from male perpetrators of violence (Kertesz et al 2019). The majority of women are themselves victim-survivors of FDV who are sometimes wrongly identified as the perpetrator (Kertesz et al 2019). Defensive behaviour is also common among women who use force. Women also describe using force out of frustration with the abusive behaviour used against them by their partners (Miller 2005).

While national data on women who use force are limited, the research highlights programs can be designed to respond to the needs of women who use force.

More information about this work can be found at Women who use force – Evaluation of Positive Shift.

Data gaps and development activities

Currently, national data on the extent of violence perpetration in Australia are not available. Data on people who use violence, perpetrators and offenders are largely drawn from administrative sources and rely on violence being detected or reported, and data being collected on the person who used violence.

Work to improve the evidence base about people who use violence has largely been focused on service responses, for example:

- The National Crime and Justice Data Linkage Project aims to link administrative datasets from across the criminal justice sector, including police, criminal courts, corrective services, and juvenile justice.

- The development of a prototype specialist crisis FDV services data collection could be expanded, in the longer term, to the collection of national information about perpetrator characteristics and related perpetrator services, including pathways and referrals into perpetrator intervention services.

More general discussions about gaps and data improvements can be found in Key information gaps and development activities.

More information

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2023) Personal safety, Australia, ABS website, accessed 16 June 2023.

ABS (2024a) Criminal Courts, Australia, ABS website, accessed 5 April 2024.

ABS (2024b) Recorded crime - Offenders, ABS website, accessed 22 February 2024.

ADFVDRN (Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network) and ANROWS (Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety) (2022) Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network data report: Intimate partner violence homicides 2010–2018, ANROWS Research report 03/2022, accessed 8 August 2022.

Boxall H, Doherty L, Lawler S, Franks C and Bricknell S (2022) The “Pathways to intimate partner homicide” project: Key stages and events in male-perpetrated intimate partner homicide in Australia, ANROWS Research report, 04/2022, accessed 8 August 2022.

Brain Injury Australia (2018) The prevalence of acquired brain injury among victims and perpetrators of family violence, accessed 6 September 2023.

Clare CA, Velasquez G, Martorell GM, Fernandez D, Dinh J and Montague A (2021) ‘Risk factors for male perpetration of intimate partner violence: A review’, Aggression and Violent Behavior 56:101532.

Curtis A, Vandenberg B, Mayshak R, Coomber K, Hyder S, Walker A, Liknaitzky P and Miller PG (2019) ‘Alcohol use in family, domestic and other violence: Findings from a cross‐sectional survey of the Australian population’, Drug and Alcohol Review, 38(4):349–58.

DSS (Department of Social Services) (2022) National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022–2032, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 19 October 2022.

FARE (Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education) (2015) National framework for action to prevent alcohol-related family violence, FARE, accessed 8 August 2022.

Fitz-gibbon K, Meyer S, Boxall H, Maher J and Roberts S (2022) Adolescent family violence in Australia: A national study of prevalence, history of childhood victimisation and impacts, ANROWS, accessed 17 March 2023.

Flood M, Brown C, Dembele L, and Mills K. (2022) Who uses domestic, family, and sexual violence, how, and why? The State of Knowledge Report on Violence Perpetration. Brisbane: Queensland University of Technology.

Flood M and Dembele L (2021) ‘Putting perpetrators in the picture’, QUT Centre for Justice Briefing Paper, QUT, accessed 10 January 2023.

Foran HM and O’Leary KD (2008) ‘Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review’, Clinical Psychology Review, 28(7), 1222–1234.

Graham K, Bernards S, Wilsnack SC & Gmel G (2011) ‘Alcohol may not cause partner violence but it seems to make it worse: A cross national comparison of the relationship between alcohol and severity of partner violence’, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(8), 1503–1523.

Gracia E, Lila M and Santirso FA (2020) ‘Attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women in the European Union: A systematic review’, European Psychologist, 25(2), 104–121.

Karystianis G, Simpson A, Adily A, Schofield P, Greenberg D, Wand H, Nenadic G and Butler T (2020) ‘Prevalence of Mental Illnesses in Domestic Violence Police Records: Text Mining Study’, J Med Internet Res 2020:22(12):e23725.

Kertesz M, Humphreys C, Larance LY, et al (2019) ‘Working with women who use force: a feasibility study protocol of the Positive (+)SHIFT group work programme in Australia’, BMJ Open.

Laslett AM, Catalano P, Chikritzhs T, Dale C, Doran C, Ferris J and Wilkinson C (2010) ‘The range and magnitude of alcohol’s harm to others,’ AER Centre for Alcohol Policy Research, Turning Point Alcohol and Drug Centre.

Mayshak R, Cox R, Costa B, Walker A, Hyder S, Day A, Coomber K, Taylor N and Miller P (2018) Alcohol/Drug-Involved Family Violence in Australia (ADIVA) - Research bulletin, AIC, accessed 10 January 2023.

Miller P, Cox E, Costa B, Mayshak R, Walker A, Hyder S and Day A (2016) Alcohol/drug-involved family violence in Australia (ADIVA), AIC, accessed 10 January 2023.

Miller SL (2005) Victims as offenders: the paradox of women’s violence in relationships, Rutgers University Press, NJ.

Morgan A & Gannoni A 2020. 'Methamphetamine dependence and domestic violence among police detainees', Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice no. 588, AIC.

Ogilvie J, Thomsen L, Barton J, Harris DA, Rynne J and O’Leary P (2022) Adverse childhood experiences among youth who offend: Examining exposure to domestic and family violence for male youth who perpetrate sexual harm and violence, ANROWS, accessed 10 January 2023.

Our Watch (2022) Change the story: A shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women in Australia, Our Watch, accessed 10 January 2023.

Productivity Commission (2024) Report on Government Services 2024 Part C, Section 7, Courts, Productivity Commission website, accessed 22 February 2024.

Salter M, Nolan J, Woodlock D, Whitten T, Peleg N, Tyler M, Naldrett G and Breckenridge J (2023) Identifying and understanding child sexual offending behaviour and attitudes among Australian men, Australian Human Rights Institute, University of New South Wales, accessed 2 January 2024.

Sullivan T, Faulconbridge E, Bricknell S and McAlister M (2024) Sexual offending in Australia 2021–22, AIC, accessed 11 July 2024.

Sutherland G, McCormack A, Pirkis J, Holland K and Vaughan C (2015) Media representations of violence against women and their children: State of knowledge paper, ANROWS, accessed 10 January 2023.

- Previous page Coercive control