Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

Key findings

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people are overrepresented as both victim-survivors and perpetrators of family and domestic violence (that is, violence that occurs within family or intimate relationships) (Cripps 2023). ‘Family violence’ is the preferred term for family and domestic violence within First Nations communities, as it covers the extended families, kinship networks and community relationships in which violence can occur (Cripps and Davis 2012). Family violence can lead to severe social, cultural, spiritual, physical and economic impacts for First Nations communities, especially for women and children (HRSCSPLA 2021).

The National Plan to End Violence against Women and their Children 2022–2032 (The National Plan) has recognised First Nations people as a priority group in their efforts to address, prevent and respond to gender-based violence in Australia (DSS 2022). The National Plan supports measures designed to achieve Target 13 in the National Agreement on Closing the Gap, which is to reduce the rate of all forms of family violence against First Nations women and children by at least 50% by 2031, as progress towards zero (DSS 2022).

The Australian Government has released a dedicated action plan aimed at reducing the rate of First Nations child abuse and neglect and its intergenerational impacts, namely the Safe and Supported: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander First Action Plan 2023–2026 (DSS 2023). The Government has also committed to developing a standalone First Nations National Plan for Family Safety in recognition of the disproportionately high rates of violence against First Nations women and children (NIAA 2023a).

This topic page focuses on the prevalence, nature, responses to, and outcomes of, family and sexual violence among First Nations people. For information on these issues for all people in Australia and other population groups, see relevant topic pages across this report.

The Australian Government defines Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as people who: are of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent; identify as being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin; and are accepted as such in the communities in which they live or have lived. In most data collections, a person is considered to be First Nations if they identified themselves, or were identified by another household member, as being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin.

The AIHW uses ‘non-Indigenous Australians’ when describing people who are not identified as being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin, except where people whose Indigenous status is ‘not stated’ have been included with the non-Indigenous group. In this case, ‘other Australians’ will be used.

Capturing accurate data on First Nations people is essential for improving policy formulation, program development and service delivery. The Australian Government is working with First Nations organisations and people to improve the access, relevance and governance arrangements relating to First Nations data (NIAA 2023b).

What do we know?

Colonisation, which involved the removal from land and cultural dispossession has resulted in social, economic, physical, psychological and emotional problems for First Nations people across generations. Family violence against First Nations people must be understood as both a cause and effect of social disadvantage and intergenerational trauma (Closing the Gap Clearinghouse 2016).

Factors associated with family violence

There are many factors that may contribute to the risk and experience of family violence. They can include gendered drivers of violence (such as rigid gender norms), demographic factors (such as age and socioeconomic background), mental health history, incarceration, alcohol and other drug use, and access to support (DSS 2022; WHO 2010). Meanwhile, factors such as cultural identity, family and kinship, country and caring for country, knowledge and beliefs, language and self-determination are protective towards First Nations people’s health and wellbeing (AIHW 2023a).

First Nations people can face unique risk factors that contribute to their high levels of family violence, with the main underlying drivers intersecting and cumulative.

See also Factors associated with FDSV.

Ongoing impacts of colonisation

The ongoing impacts of colonisation for First Nations people include personal, collective and intergenerational trauma, individual and systemic racism and oppression, and the disruption of traditional cultures, relationships and community norms about violence. For non-Indigenous Australians, the history of dispossession has contributed to racialised structural inequalities of power and the normalisation and perpetration of racist social norms and practices. These risk factors can contribute to and be exacerbated by socio-economic disadvantage, poor physical and mental health, and destructive coping behaviours among First Nations people (Our Watch 2018; Cripps and Davis 2012; DSS 2022; Langton et al. 2020).

Gendered factors

The gendered drivers of violence against First Nations women include the intersection of racism and sexism, and the impacts of colonial patriarchy on gender roles, and interpretation of what constitutes violence against women that can differ from western norms (Our Watch 2018; Langton et al. 2020).

Barriers to reporting or seeking assistance for family violence

Estimates suggest that around 90% of violence against First Nations women and most cases of sexual abuse of First Nations children are undisclosed (Willis 2011). First Nations people can face a range of barriers to reporting violence and accessing formal support, including:

- a lack of understanding of legal rights and options and how to access support

- a lack of cultural competency and discriminatory practices across the support sector

- a lack of awareness and knowledge in what constitutes violence

- a lack of access to transportation and/or communication channels, especially for those living in rural and remote areas

- fear of child removal if disclosing family violence

- fear that parental separation will threaten cultural connection and community cohesion

- fear of reprisal by perpetrator or ‘payback’ – a form of First Nations customary law aimed at resolving grievances that could lead to violent retribution against the victim-survivor

- fear of losing their home in social or community-controlled housing settings

- fear of not being believed and misidentification of victim-survivors as perpetrators due to defensive violence

- mistrust of mainstream legal and support services to understand and respect the needs, autonomy and wishes of victim-survivors

- mistrust of First Nations-run service providers to maintain client confidentiality

- community pressure not to report violence to avoid increased incarceration of First Nations men

- communication barriers

- racism and discrimination

- poverty and social isolation

- shame and embarrassment

- belief that they should seek support from kin or people within their inner circle, and/or that the incident is a private matter (Fiolet et al. 2019; Backhouse and Toivonen 2018; Willis 2011; Langton et al. 2020).

Other than kin and people within the victim-survivor’s inner circle, community-led informal support that prioritise cultural healing also play an important role in First Nations family violence response. Cultural healing processes acknowledge culture as a key protective factor for First Nations people’s health and wellbeing (Backhouse and Toivonen 2018; AIHW 2023a). For example, the cultural practices of storytelling and ‘Dadirri’ (‘deep listening’) allow victim-survivors to share their stories in a culturally safe setting, while others are encouraged to listen deeply by connecting with their story, reflecting on silence, understanding their pain and respecting their strength (Cripps 2023).

See also How do people respond to FDSV?.

What data are available?

Data about the prevalence of family violence among First Nations people come from national surveys and administrative datasets. Some administrative data are available to report on the responses to and impacts of family violence.

The current leading source of data for First Nations people is the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey. However, as the survey is designed to collect data on a broad range of topics, it is unable to produce the breadth of data on family violence available in the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Personal Safety Survey. Information on Indigenous status is not collected in the ABS Personal Safety Survey.

The terminology used for First Nations people in this topic page can vary depending on what is used within the data source.

It is difficult to obtain robust data on experiences of family violence for First Nations children. Due to the sensitive nature of the subject, most large-scale population surveys focus on adults.

The Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS) was a cross-sectional survey on the experience of child maltreatment conducted in 2021. While the ACMS did not exclude First Nations people, it was determined that it was not ethically or methodologically appropriate to disaggregate data by Indigenous status for the survey (Haslam et al. 2023).

As part of the National Strategy to Prevent and Respond to Child Sexual Abuse 2021–2030, the Australian Government has committed to conducting a second wave of the ACMS. This will include specific methods to capture representative data for First Nations people, with a focus on ages 16–24 to produce estimates for recent (past 12 months) child maltreatment (National Office for Child Safety 2021).

- Aboriginal Families Study

- ABS Criminal Courts

- ABS National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS)

- ABS National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS)

- ABS Recorded Crime, Offenders

- ABS Recorded Crime, Victims

- AIC National Homicide Monitoring Program

- AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database

- AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services (SHS) Collection

- ANROWS Technology-facilitated Abuse study

- Child Protection National Minimum Data Set

- Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC)

- Suicides of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Victoria

For more information about these data sources, see Data sources and technical notes.

What do the data tell us?

Physical assault by a family member

-

2 in 3

First Nations people aged 15 and over in 2018-19 who had experienced physical harm in the last 12 months reported the perpetrator was an intimate partner or family member

Source: ABS National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey

The latest National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS, 2018–19) showed that 2 in 3 (67% or 20,800) First Nations people aged 15 and over who had experienced physical harm in the 12 months before the survey reported the perpetrator was a family member (a former or current intimate partner or other family member) (ABS 2019a).

ABS Recorded Crime collections are based on crimes recorded by police in each state and territory and published according to the Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification (ANZSOC). Only a select set of crimes are considered for inclusion in the ABS family violence data in the Recorded Crime collections, with individual incidents only included in family violence collections when:

- the relationship of offender to victim falls within a specified family or domestic relationship (spouse or domestic partner, parent, child, sibling, boyfriend/girlfriend or other family member to the offender) and/or

- a family and domestic violence flag has been recorded, following a police investigation and does not contradict any recorded detailed relationship of offender to victim information (see Data sources and technical notes).

The ABS Recorded Crime collections refer to these crimes as “family and domestic violence-related”, while this topic page refers to these crimes as perpetrated “by a family member”.

Recorded Crime – Victims data included in this topic page are only available for New South Wales, South Australia, the Northern Territory, and sometimes Queensland; while Recorded Crime – Offenders data included are available for the four jurisdictions as well as the Australian Capital Territory. As of 30 June 2021, the proportion of First Nations people living in these jurisdictions include:

- 4.2% (or 340,000) in New South Wales

- 2.9% (or 52,100) in South Australia

- 31% (or 76,500) in the Northern Territory

- 5.2% (or 273,000) in Queensland

- 2.1% (9,500) in the Australian Capital Territory (ABS 2023a).

Across jurisdictions with published data (New South Wales, South Australia and the Northern Territory) in 2022, police-recorded crime data indicated that the First Nations victimisation rate of assault by a family member was:

- 1,700 per 100,000 (or 5,100) First Nations people in New South Wales

- 4,800 per 100,000 (or 2,300) First Nations people in South Australia

- 7,700 per 100,000 (or 6,100) First Nations people in the Northern Territory (ABS 2023b; Figure 1).

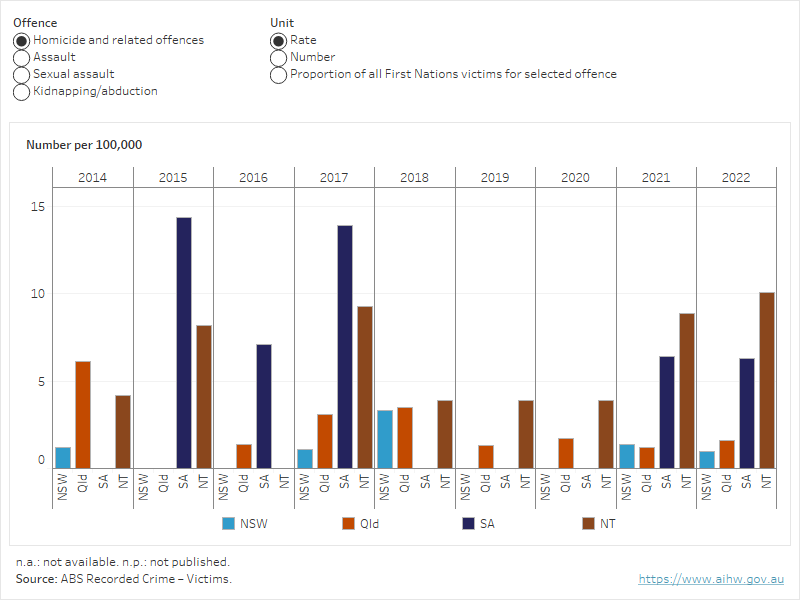

Figure 1: First Nations victims of crimes perpetrated by a family member, for selected states and territories, 2014–2022

Figure 1 shows the rate, number and proportion of First Nations victims of crimes perpetrated by a family member in 2014-2022 for New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and the Northern Territory.

Police-recorded sexual assault

Across jurisdictions with published police-recorded crime data (New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, and the Northern Territory) in 2022, the victimisation rate of sexual assault ranged from 209 per 100,000 (or 100) First Nations people in South Australia to 375 per 100,000 (or 1,100) First Nations people in New South Wales (ABS 2023b).

Between 2010 and 2022, First Nations victimisation rates for sexual assault varied between states and territories and over time (Figure 2; ABS 2023b).

Figure 2: First Nations victims of sexual assault, for selected states and territories, 2010–2022

Figure 2 shows the rate and number of First Nations victims of sexual assault for New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and the Northern Territory in 2010-2022.

For sexual assault by a family member, the victimisation rate ranged from 89 per 100,000 (or 70) First Nations people in the Northern Territory to 156 per 100,000 (465) First Nations people in New South Wales. Between 2014 and 2022, these rates varied between states and territories and over time. Since 2018, the First Nations victimisation rate for sexual assault by a family member was lowest for the Northern Territory, compared with New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia (Figure 1; ABS 2023b).

The use of technology

Increasingly, mobile and digital technologies are utilised by perpetrators to facilitate family violence. When interpersonal harms are conducted via technology, such as online harassment, image-based abuse and monitoring behaviours, they are considered technology-facilitated abuse (TFA).

Data on the prevalence of TFA among First Nations people are available from a nationally representative survey of about 4,600 adults in 2022. The survey used random probability-based sampling methods and weighting to allow results to be generalisable to the adult population in Australia (Powell et al. 2022). The survey found that among First Nations respondents:

- 7 in 10 (70%) reported experiencing TFA at least once in their lifetime, compared with 1 in 2 (51%) for all respondents

- 2 in 5 (42%) reported having engaged in TFA perpetration in their lifetime, compared with about 1 in 4 (23%) for all respondents (Powell et al. 2022).

For more information on TFA, see Stalking and surveillance.

What are the responses to family violence?

Responses to family violence include a mix of informal responses (such as contact with friends and family) and formal responses (such as assistance from police, legal services, specialist crisis services, child protection services or health professionals). This section focuses on formal responses due to data availability. For more information on responses to family violence for the general population, see How do people respond to FDSV?.

Despite the lack of data on the effectiveness of First Nations-specific family violence responses, existing research have identified effective specialist family violence responses should include:

- community involvement, engagement and acceptance

- cultural competency

- integrated service delivery

- planning for long-term sustainability

- holistic, flexible and trauma-informed approaches

- building on existing culturally appropriate initiatives and community capabilities (Closing the Gap Clearinghouse 2016; SNAICC et al. 2017).

Police

The ABS collates national statistics on crimes recorded by the police relating to victims and offenders of family violence (see Box 3 and Data sources and technical notes for details). Although information on family violence is available from these administrative data sets, a high proportion of family violence is not disclosed to police for a range of reasons, see Barriers to reporting or seeking assistance for family violence. The fear of the consequences of seeking help from police was highlighted in the Parliamentary Inquiry into family, domestic and sexual violence, as it is known that some First Nations victim-survivors were previously criminalised due to misidentification as perpetrators or unrelated offences (such as unpaid fines) when police attended the family violence situation (HRSCSPLA 2021).

A large proportion of assault victims are victims of family violence

Across jurisdictions with published data (New South Wales, South Australia and the Northern Territory) in 2022, the ABS Recorded Crime – Victims data collection found that First Nations assault victims:

- were commonly victims of family violence-related assault (54–70%), and

- most commonly identified perpetrators of the assault as partners or ex-partners (32–52%) (ABS 2023b).

Sexual assault victims are most likely to be female and under 18 years old

Most First Nations victims of sexual assault were female (70–93%) in 2022.

Across jurisdictions with published data (New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, and the Northern Territory) in 2022, First Nations victims of sexual assault were predominantly female, ranging from 70% in New South Wales to 93% in South Australia (ABS 2023b).

Except for South Australia, the rate of sexual assault was higher for First Nations people aged under 18 than those aged 18 and over (based on age at report), ranging from 1.3 times as high in the Northern Territory to 1.8 times as high in Queensland. This is consistent with the pattern for all people in Australia, but with higher rate ratios, where the rate of sexual assault was 1.6 to 3.6 times as high for people aged under 18 than those aged 18 and over (based on age at report) (ABS 2023b).

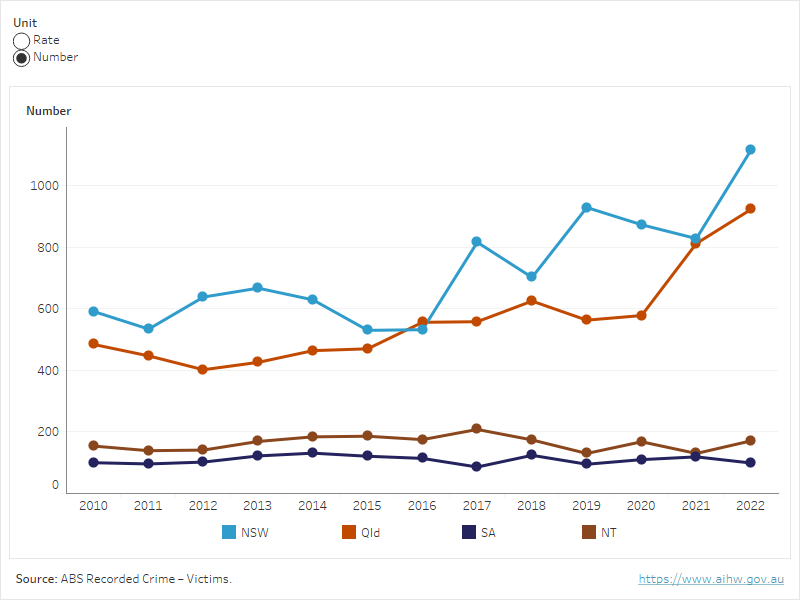

Perpetrators of family violence are most likely to be male

The ABS Recorded Crime – Offenders 2022–23 data collection also contains information about people committing offences related to family violence. Data for First Nations offenders are available for New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory only. First Nations offender rates are expressed per 100,000 of the First Nations population aged 10 years and over (for more information on this collection, see Data sources and technical notes).

The offender rate for offences related to family violence was higher for First Nations males than females, ranging from 2.7 times higher in New South Wales to 4.1 times higher in the Australian Capital Territory (Figure 3; ABS 2024b).

The Indigenous status of perpetrators of violence against First Nations women is not available for reporting. Note that such violence is perpetrated by men of all cultural backgrounds, not just First Nations men (Our Watch 2018).

Figure 3: First Nations offenders of family violence, for selected state and territories, by sex, 2022–23

Figure 3 shows the rate and number of First Nations offenders of family violence for the Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales, Northern Territory, Queensland and South Australia in 2022-23.

Perpetrators of sexual assault are usually known to the victim

First Nations victims of sexual assault are likely to know the perpetrator. The proportion of First Nations victims who knew their perpetrators ranged from 57% in the Northern Territory to 88% in New South Wales in 2022 (ABS 2023b).

Legal

Family and domestic violence protection orders

A common legal response to family violence in Australia is to obtain a personal safety intervention order (PSIO) or family and domestic violence protection order (DVO). First Nations people are over-represented within the DVO system as both applicants and respondents (see Box 4).

A domestic violence order (DVO) is a civil order issued by a court that forbids a perpetrator of family violence from committing further abuse against the victim-survivor. It is a criminal offence to breach a DVO. A Queensland study analysed the DVOs that were established in civil courts and those that were referred to criminal courts during 2013–14. The people named as perpetrators in these DVOs were offered the opportunity to self-report their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status.

In 2013–14, almost 23,500 people were named as perpetrators in DVOs issued in Queensland, of whom 1 in 5 (21%) identified as First Nations people. First Nations women were slightly more likely to be named as perpetrators than non-Indigenous women (23% of First Nations perpetrators and 20% of non-Indigenous perpetrators).

DVOs taken out against First Nations people were more likely to have been lodged by the police. Of all DVOs lodged in Queensland, 79% were initiated by the police, and in cases where the perpetrator identified as First Nations, 90% were initiated by the police. In 2013–14, about 6,900 people were defendants facing criminal charges for contravening a DVO in Queensland, of whom 1 in 3 (34%) identified as First Nations people. The proportion of defendants found guilty was similar for First Nations defendants (89%) and all defendants (88%). However, a higher proportion of First Nations defendants received a custodial order (43%), compared with all defendants (27%).

For more information on DVOs, see Legal systems.

Source: Douglas & Fitzgerald 2018.

Most First Nations defendants who go to court for family violence offences are found guilty

Data from the ABS Criminal Courts, Australia, 2022–23 data set are available for First Nations defendants who had one or more family violence cases finalised in criminal courts in New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory. Finalised defendants include all individuals for whom charges have been formally completed by a court. These defendants may be acquitted, found guilty, or had their cases withdrawn or transferred. To avoid double counting of defendants who were transferred and subsequently finalised by another method, transfers are excluded in the calculation of proportions (ABS 2024a).

The proportion of First Nations defendants who were found guilty were:

- 92% (6,900) in Queensland

- 91% (3,200) in the Northern Territory

- 76% (7,600 defendants) in New South Wales

- 73% (235 defendants) in Tasmania

- 57% (48 defendants) in the Australian Capital Territory

- 40% (500 defendants) in South Australia (Figure 4; ABS 2024a).

The proportion of First Nations defendants who were found guilty was similar to the proportion for other Australian defendants (that is, non-Indigenous defendants, including people whose Indigenous status was not stated for the ACT) who were found guilty. This ranged from 34% in South Australia to 83% in Queensland (ABS 2024a).

Figure 4: First Nations defendants of family violence offences finalised in criminal courts, by method of finalisation, for selected states and territories, 2022–23

Figure 4 shows the number of First Nations defendants of family violence offences finalised in criminal courts by method of finalisation in 2022-23 for New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory.

Acts intended to cause injury is the most common principal offence among First Nations family violence defendants

Acts intended to cause injury are acts intended to cause non-fatal physical injury or mental harm to another person and where there is no sexual or acquisitive element. This includes behaviours such as physical assault and stalking (ABS 2011).

Across jurisdictions with published data, the most common principal family violence offence among First Nations defendants was acts intended to cause injury in 2022–23, ranging from 46% in Tasmania to 71% of all family violence offences in South Australia. The exception was Queensland, where almost 2 in 3 (65%) First Nations family violence defendants finalised had a principal offence of breach of violence orders (ABS 2024a).

Hospitalisations

Data on hospitalisations for injury from assault come from the AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database. In 2022–23, there were about 3,400 hospitalisations for injuries related to family violence involving First Nations people (2,600 females and 800 males) (Figure 5; AIHW 2024a).

As information on cause of injury (such as assault) is not available in national emergency department data, family violence hospitalisations do not include presentations to emergency departments and underestimate overall hospital activity related to family violence. These hospitalisations also relate to more severe (and mostly physical) experiences of family violence (AIHW 2022c). See Health services for more information on how family violence hospitalisations are measured.

Figure 5: Family violence hospitalisations among First Nations people, by sex, 2018–19 to 2022–23

Figure 5 shows the number and rate of family violence hospitalisations among First Nations men and women from 2018-19 to 2022-23.

Most hospitalisations for assault are a result of family violence

Over 7 in 10 (72%) assault hospitalisations involving First Nations people in 2022–23 were due to family violence.

In cases where a perpetrator was specified, over 7 in 10 (72%, or 3,400) assault hospitalisations involving First Nations people were due to family violence in 2022–23. Specifically, 45% were due to assault by a spouse or domestic partner, 2.7% by a parent and 24% by another family member (AIHW 2024a).

This varied by age group, with First Nations people most likely to be hospitalised for assault by:

- their spouse or domestic partner, for those in the age groups covering 15 to 54 years (with proportions ranging from 41%–52%)

- a parent, for children aged 0–14 (43%)

- another family member, for those aged 55–64 (41%) and 65+ years (54%) (AIHW 2024a).

For First Nations women aged 15 and over, a spouse or domestic partner was most commonly reported (59%, or 1,800) as the perpetrator for hospitalisations due to assault among all cases where a perpetrator was specified. The hospitalisation rate due to assault by a spouse or domestic partner was highest for women aged 35–44 (1,093 per 100,000 hospitalisations) (AIHW 2024a).

For First Nations men aged 15 and over, a family member other than a spouse, domestic partner or parent was most commonly reported (31%, or 445 cases) as the perpetrator for hospitalisations due to assault. The hospitalisation rate due to assault by another family member was highest for men aged 35–44 (273 per 100,000 hospitalisations) (Figure 6; AIHW 2024a).

Figure 6: Family violence hospitalisations among First Nations people, by relationship to perpetrator, 2022–23

Figure 6 shows the number and rate of family violence hospitalisations among First Nations people, by relationship to perpetrator.

Most hospitalisations due to family violence assault involve bodily force

Among First Nations males and females hospitalised for family violence-related injuries in 2022-23:

- about 51% (1,300) of females and 38% (300) of males were assaulted by bodily force (excluding sexual assault by bodily force)

- one-third (33%) of females were assaulted with an object: 21% (560) with a blunt object and 12% (310) with a sharp object

- more than half (52%) of males were assaulted with an object: 28% (220) with a sharp object and 24% (195) with a blunt object

- hanging, strangulation and suffocation was specified as the cause of injuries for 100 (3.9%) females (AIHW 2024a).

Head and/or neck injuries are the most common injuries inflicted by a family member

Among hospitalisations of First Nations people for assault-related injuries perpetrated by a family member, 70% (1,800) females and 58% (440) males experienced injuries to the head or neck in 2022–23. This included 320 females and 75 males hospitalised for brain injury (Figure 7; AIHW 2024a).

Figure 7: Family violence hospitalisations among First Nations people, by type of injury and sex, 2022–23

| Type of injury | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|

| Head and/or neck | 70.3% | 57.9% |

| Trunk | 25.6% | 24.7% |

| Shoulder, arm or hand | 35.1% | 39.0% |

| Hip, leg or foot | 20.2% | 14.3% |

| Burns | 0.9% | 1.2% |

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

AIHW NHMD

|

Data source overview

First Nations people living in Remote and very remote areas are more likely to be hospitalised due to family violence

In Remote and very remote areas in 2022–23, the hospitalisation rate for family violence was:

- about 2,091 per 100,000 (or 1,600) for First Nations females, compared with 275 per 100,000 (or 550) for those living in Inner and outer regional areas and 215 per 100,000 (or 375) in Major cities

- 653 per 100,000 (or 510) for First Nations males, compared with 87 per 100,000 (or 175) for those living in Inner and outer regional areas and 59 per 100,000 (or 100) in Major cities (AIHW 2024a).

First Nations people are more likely to be hospitalised for family violence than non-Indigenous Australians

First Nations people were 33 times as likely to be hospitalised for family violence as non-Indigenous Australians.

In 2022–23, the age-standardised hospitalisation rate for family violence for First Nations people (431 per 100,000) was 33 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (13 per 100,000) (AIHW 2024a).

The age-standardised hospitalisation rate for family violence for:

- First Nations females (650 per 100,000, or 2,600) was 34 times as high as for non-Indigenous females (19 per 100,000, or 2,300)

- First Nations males (209 per 100,000, or 800) was 29 times as high as for non-Indigenous males (7.3 per 100,000, or 910) (AIHW 2024a).

Specialist homelessness services

Specialist homelessness services (SHS) provide assistance to people who are experiencing or at risk of homelessness, including clients who have experienced family violence. Data on people seeking support from SHS agencies are drawn from the AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC). The SHSC reports on clients experiencing family violence of any age, including both victim-survivor and perpetrator services provided. The AIHW Specialist homelessness services annual report includes additional details on Clients who have experienced family and domestic violence.

Family violence is one of the main reasons First Nations clients seek assistance

Of the 259,000 clients who accessed SHS in 2022–23 and whose Indigenous status was known, about 74,700 (29%) were First Nations people. Of these First Nations clients:

- 24% (17,800) cited family violence as their main reason for seeking assistance

- 26% (19,400) requested assistance for family violence (AIHW 2023b).

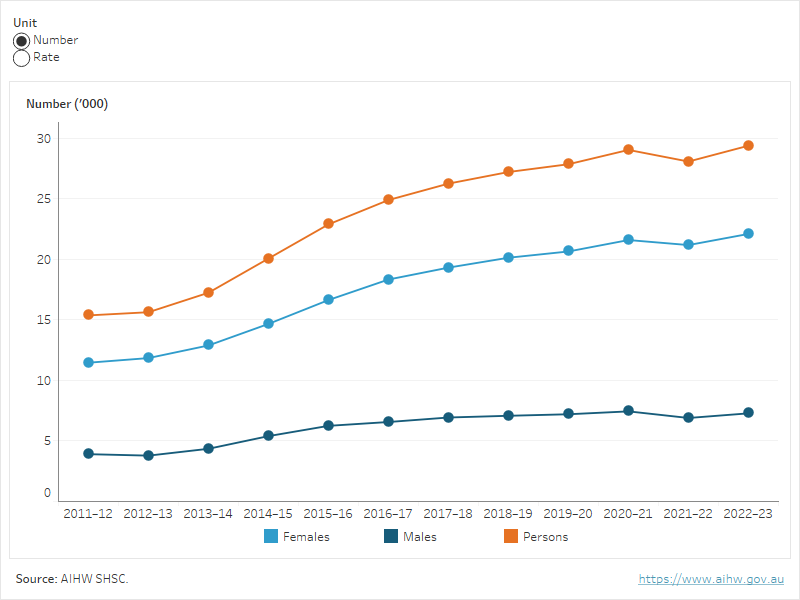

Between 2011–12 and 2022–23, the rate of First Nations SHS clients who have experienced family violence was higher for females than males. The rate has increased over time from 214 per 10,000 people in 2011–12 to 328 per 10,000 people in 2022–23 (Figure 8). Changes in the number of First Nations clients over time may reflect improved Indigenous status data among people receiving SHS support (AIHW 2023b).

Figure 8: First Nations specialist homelessness services clients who have experienced family violence, by sex, 2011–12 to 2022–23

Figure 8 shows the rate and number of First Nations specialist homelessness services clients who have experienced family violence from 2011-12 to 2022-23, by sex.

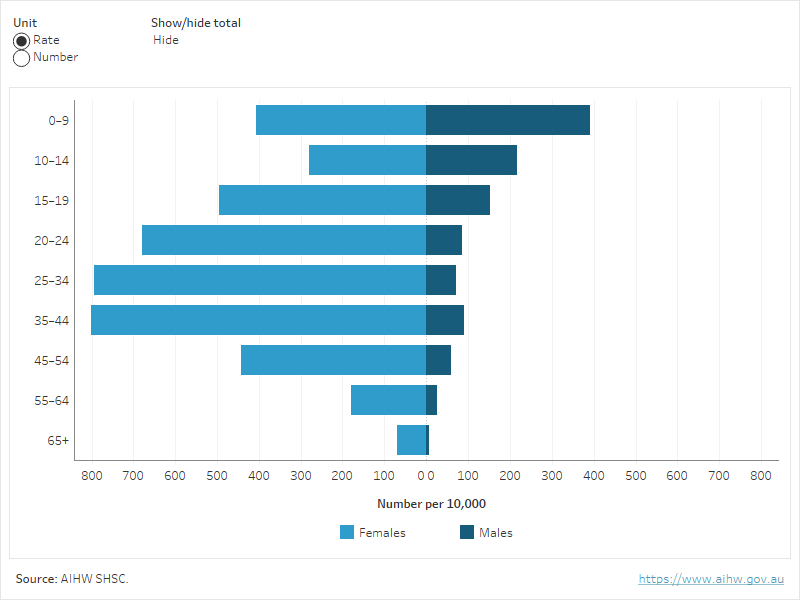

In 2022–23, the rate of First Nations SHS clients who have experienced family violence was highest for females aged 35–44 (802 per 10,000 people) across all age groups. Among First Nations male SHS clients, those aged 0–9 had the highest rate (392 per 10,000 people) (Figure 9; AIHW 2024c).

Figure 9: First Nations specialist homelessness services clients who have experienced family violence, by age group, 2022–23

Figure 9 shows the rate and number of First Nations specialist homelessness services clients who have experienced family violence in 2022-23, by age group.

For more information on family violence among SHS clients, see Housing.

Child protection

First Nations children are particularly at risk of experiencing the direct and indirect impacts of family violence, which contributes to the over-representation of First Nations children in Australia’s child protection system (SNAICC et al. 2017). First Nations children and young people may face additional challenges as a result of multiple disadvantages, such as loss of culture, racism and discrimination (ACYP 2018).

In 2022–23, around 58,200 (169 per 1,000) First Nations children came into contact with the child protection system. This rate has increased over time from 156 per 1,000 in 2018–19 (AIHW 2024b).

Of the 45,400 children who were the subjects of substantiations of maltreatment in 2022–23, around 13,700 were First Nations children (40 per 1,000) and almost 30,300 were non-Indigenous children (5.6 per 1,000). Emotional abuse was the most common primary type of abuse substantiated for First Nations children (52%), followed by neglect (29%), physical abuse (12%) and sexual abuse (7.0%) (AIHW 2024b).

The rates of substantiations of child maltreatment were higher for First Nations infants aged less than one (72 per 1,000) and lowest for adolescents aged 15–17 (20 per 1,000) (Figure 10; AIHW 2024b).

Figure 10: First Nations children who were the subject of substantiations, by age, 2022–23

Figure 10 shows the rate and number of First Nations children who were the subject of substantiations in 2022-23, by age group.

The higher rate of First Nations children in child protection substantiations is complex, and may have been affected by:

- the legacy of past policies of forced removal

- intergenerational effects of previous separations from family and culture

- a higher likelihood of living in the lowest socioeconomic areas

- perceptions arising from cultural differences in child-rearing practices (HREOC 1997).

At 30 June 2023, around 2 in 5 children on care and protection orders or in out-of-home care were First Nations people (41% or almost 24,900 children and 44% or around 19,700 children, respectively) (AIHW 2024b).

See Child protection for more information.

What are the impacts and outcomes of family violence?

Family violence has been associated with a range of negative health impacts, including higher rates of miscarriage, pre-term birth and low birthweight, as well as other long-term health consequences for women and children (WHO 2011). See Health outcomes, Behavioural outcomes and Economic and financial impacts for more information.

There are limited national longitudinal data on the impacts and outcomes of family violence in First Nations communities, particularly for children.

Burden of disease

Burden of disease measures the impact of living with illness and injury and dying prematurely. According to the First Nations component of the 2018 Australian Burden of Disease Study (ABDS, see Box 5), child abuse and neglect contributed to 5.1% of the total disease burden and around 80 deaths for First Nations people. Among First Nations women, intimate partner violence (IPV) contributed to 2.1% of the total disease burden and around 30 deaths (AIHW 2022a).

The Australian Burden of Disease Study (ABDS) 2018 estimated the impact of various diseases, injuries and risk factors on total burden of disease for the Australian and First Nations population. It combines health loss from living with illness and injury (non-fatal burden, or YLD) and dying prematurely (fatal burden, or YLL) to estimate total health loss (total burden, or DALY) (see Glossary).

The ABDS includes estimates of the contribution made by selected risk factors on the disease burden in Australia, including intimate partner violence (IPV) and child abuse and neglect. The disease burden due to IPV is currently only available for females, as there is not sufficient published research indicating a causal link between disease burden and the risk of IPV for males.

Source: AIHW 2021

For more information on how burden of disease is determined, see Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2018, Summary.

Diseases that were causally linked to IPV

The ABDS 2018 estimated the amount of disease burden that could have been avoided if all First Nations women aged 15 and over in Australia were not exposed to IPV. In estimating this burden, 6 diseases were causally linked to exposure to IPV in females:

- depressive disorders (contributing to 20% of depressive disorders total burden in females)

- anxiety disorders (26%)

- early pregnancy loss (28%)

- homicide and violence (injuries due to violence) (62%)

- suicide and self-inflicted injuries (32%)

- alcohol use (10%) (AIHW 2022a).

The burden attributable to IPV for First Nations women (age-standardised DALY rate of 14 per 1,000 people) was 6.1 times the rate for non-Indigenous women (age-standardised DALY rate of 2.3 per 1,000 people). IPV contributed to 5.8% of the total health gap (as measured by the DALY rate difference between First Nations and non-Indigenous women) (AIHW 2022a).

Diseases that were causally linked to child abuse and neglect

Child abuse and neglect among First Nations people was causally linked to:

- anxiety disorders (contributing to 35% of anxiety disorders burden)

- depressive disorders (31%)

- suicide and self-inflicted injuries (41%) (AIHW 2022a).

The burden attributable to child abuse and neglect for First Nations people (age-standardised DALY rate of 16 per 1,000 people) was 3.9 times the rate for non-Indigenous people (age-standardised DALY rate of 4.0 per 1,000 people). Child abuse and neglect contributed to 5.2% of the total health gap (as measured by the DALY rate difference between First Nations and non-Indigenous people) (AIHW 2022a).

Family violence is associated with high psychological distress in First Nations mothers

The Aboriginal Families Study (see Box 6) identified high rates of social health issues affecting Aboriginal women and families in South Australia during pregnancy, and high levels of associated psychological distress after the birth of their babies. One in 4 Aboriginal women (25%, or 83) reported high to very high psychological distress after the birth of their baby, which is higher than estimates of maternal psychological distress among the general population (Weetra et al. 2016).

More than 1 in 2 (56%) Aboriginal women had experienced 3 or more stressful events and social health issues during pregnancy, and more than 1 in 4 (27%) had experienced 5–12 issues. A large number of Aboriginal women reported experiences of family or community conflict during pregnancy:

- 1 in 3 (30%, or 100) had been scared by other people’s behaviour

- 1 in 4 (26%, or 90) had left home due to a family argument

- 1 in 6 (16%, or 53) had been physically assaulted (Weetra et al. 2016).

The average age of participating mothers in the study was 25, with an age range of 15–43 (Weetra et al. 2016). First Nations mothers are, on average, younger than non-Indigenous mothers. Of all the mothers who gave birth in 2021, the average maternal age for First Nations mothers was about 27 years, compared with about 31 years for non-Indigenous mothers. A higher proportion of First Nations mothers were teenagers (10%), compared with 1.1% of non-Indigenous mothers (AIHW 2022b).

The Aboriginal Families Study investigates the health and wellbeing of 344 Aboriginal children born between July 2011 to June 2013 and their mothers living in South Australia. It is being conducted as a partnership between the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, the Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia and the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute. An Aboriginal Advisory Group has been guiding the development and conduct of the study. The study is expected to be completed in December 2023.

As part of the study, the mothers completed a questionnaire in the first year after the birth of their children about experiences of family and community violence during pregnancy. The questionnaire included measures of stressful events (such as serious illness or injury) and social health issues (such as housing problems, trouble with police, and drug and alcohol problems) during pregnancy, and maternal psychological distress were assessed using the Kessler-5 scale. They completed a follow-up questionnaire focused on experiences of intimate partner violence when the children were aged 5–8 years, which were measured using a culturally adapted version of the Composite Abuse Scale.

For more information on the experiences of mothers and children, see Mothers and their children.

Source: ANROWS 2023; Weetra et al. 2016.

Preliminary findings from the follow-up questionnaire (based on 170 of the women) found that about 2 in 5 (37%) had experienced any violence from a current or former partner in the previous 12 months (partner violence):

- 1 in 3 (30%) had experienced psychological violence

- 1 in 4 (25%) had experienced physical violence

- about 1 in 4 (26%) had experienced financial abuse

- about 1 in 5 (19%) had experienced all three types of partner violence (Brown et al. 2021).

A higher proportion of women who were single (59%) reported partner violence compared with women who were living with a partner (20%) (Brown et al. 2021).

Witnessing family conflict is associated with social and emotional difficulties among First Nations children

The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC) is a study among First Nations children of how a child’s early years affect their development. The study has interviewed participating families every year since 2008 and includes a sizeable population of First Nations children and their families across Australia; however, it is not based on a representative sample (DSS 2020). The primary carers were asked about their relationship with their partners in Wave 3 (2010) and again in Wave 6 (2013) (Kneebone 2015).

Among the surveyed families of between 1,200 and 1,700 First Nations children, 1 in 5 (20%) reported that their children had been upset by family arguments in the last year, with this proportion consistent over time. These children were significantly more likely to experience social and emotional difficulties (as measured by a Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire), compared with children whose parents did not report them being upset by family arguments (Kneebone 2015).

Children whose parents have had violent arguments were also more likely to experience social and emotional difficulties compared with those whose parents did not report violent arguments; however, the difference was only statistically significant in Wave 3 (Kneebone 2015).

More First Nations women are killed by partners than First Nations men

The National Homicide Monitoring Program recorded 21 First Nations victims of domestic homicide in 2022–23. There were:

- 6 victims killed by an intimate partner

- 7 victims killed by a parent

- 1 victim killed by a child

- 3 victims killed by a sibling

- 4 victims killed by other relatives (Miles and Bricknell 2024).

Over half (56%) of First Nations female victims of domestic homicide were killed by an intimate partner. Meanwhile, 1 in 12 (8.3%) First Nations male victims of domestic homicide were killed by an intimate partner. First Nations male victims of domestic homicide were more commonly killed by parents (42%) (Miles and Bricknell 2024; Figure 11). These data should be interpreted with caution due to small numbers.

Figure 11: First Nations domestic homicide victims, by type of homicide and sex of victim, 2022–23

| Victim relationship with offender | Female victim | Male victim | Persons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intimate partner | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Child | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| Parent | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Sibling | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Other relative | 1 | 3 | 4 |

Note:

- 'Child' includes victims who were adult children of offender.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

AIC NHMP

|

Data source overview

Data used by the Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network, which only includes intimate partner homicides that had a history of violence between the offender and victim, indicate that:

- of the 240 female victims of homicide by a male intimate partner, 1 in 4 (25%) were First Nations women

- of the 65 male victims of homicide by a female intimate partner, 2 in 5 (40%) were First Nations men (ADFVDRN and ANROWS 2022).

For more information, see Domestic homicide.

Across jurisdictions with published data (New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and the Northern Territory) in 2022, police-recorded crime data indicated that the victimisation rate of homicide by a family member was:

- 1.0 per 100,000 First Nations people in New South Wales

- 1.6 per 100,000 First Nations people in Queensland

- 6.3 per 100,000 First Nations people in South Australia

- 10 per 100,000 First Nations people in the Northern Territory (ABS 2023b; Figure 1).

Family violence is a risk factor for suicide

Violent behaviour is a risk factor for suicide, regardless of the presence of other mental health conditions or substance use (Cripps 2023). The Coroners Court of Victoria identified experience of abuse (85%), conflicts with family members (55%), conflicts with a partner (49%) and experiences of family violence with a partner (49%) as some of the major interpersonal and contextual stressors among First Nations people who died by suicide from 2018 to 2021. The court also found that 1 in 3 (34%) First Nations people who died by suicide had a childhood history of exposure to family violence, including witnessing and/or experiencing family violence during childhood (Coroners Court of Victoria 2023).

Is it the same for everyone?

The risk and experience of family violence among First Nations people can vary. Different aspects of a person’s identity (such as gender, socioeconomic status and disability) can expose the individual to overlapping and/or increased sources of discrimination and marginalisation, which can lead to increased risk and severity of family violence (Victoria State Government 2019).

Although national data on the experiences of family violence among First Nations people who also belong to other population groups are limited, some data are available for First Nations people with disability and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer, Sistergirl or Brotherboy (LGBTIQASB+) First Nations people.

See Factors associated with FDSV for more information on intersecting risk factors associated with family violence.

First Nations people with disability

First Nations people are more likely to have disability than non-Indigenous Australians. Almost 1 in 4 (24%, or 140,000) First Nations people living in households (excluding those in very remote areas and discrete First Nations communities) reported having disability in 2018, compared with 18% in the total population (ABS 2019b, 2021).

The latest National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS, 2014–15) showed that First Nations people who reported experiencing physical violence by a family member in the past 12 months were more likely to have disability. Among First Nations people who reported physical violence from a family member, more than half (54%, or 17,700) had a disability. More than half (56%, or 12,800) women and just under half (49%, or 4,800) men who experienced physical violence from a family member in the last 12 months had a disability. However, this result should be interpreted with caution due to small sample sizes (ABS 2016).

For more information on family violence among people with disability, see People with disability.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer, asexual, Sistergirl or Brotherboy (LGBTIQASB+) First Nations people

Brotherboy and Sistergirl are terms used by First Nations people to describe gender diverse people who have a male and female spirit that take on male and female roles within the community respectively.

There are no national data on the prevalence of family violence among LGBTIQASB+ First Nations people. However, it is known that First Nations LGBTIQASB+ communities experience a range of significant and intersecting points of discrimination and marginalisation (DSS 2022). A qualitative study on First Nations LGBTIQASB+ people’s experiences of family violence found a high prevalence of violence experienced by LGBTIQASB+ people, where intimidation, bullying and threats of violence were commonly used to make the victim-survivor feel unsafe or excluded and/or force the victim-survivor to hide their gender identity and sexual orientation. The study also found that negative reactions and behaviours were reported more within extended families, older generations and rural or remote communities (Soldatic et al. 2023).

For more information on family violence among LGBTIQA+ people, see LGBTIQA+ people.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2011) ‘02 Acts intended to cause injury’, Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification (ANZSOC), ABS website, accessed 21 July 2023.

ABS (2016) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey, 2014–15, Table Builder, ABS website, accessed 20 April 2023.

ABS (2019a) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, ABS website, accessed 16 August 2023.

ABS (2019b) Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: summary of findings, ABS website, accessed 19 April 2023.

ABS (2021) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability, ABS website, accessed 19 April 2023.

ABS (2023a) Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, ABS website, accessed 1 September 2023.

ABS (2023b) Recorded Crime – Victims, ABS website, accessed 31 July 2023.

ABS (2024a) Criminal Courts, Australia, ABS website, accessed 5 April 2024.

ABS (2024b) Recorded Crime – Offenders, ABS website, accessed 23 February 2024.

ACYP (Office of the Advocate for Children and Young People) (2018) Report on consultations with socially excluded children and young people 2018, ACYP website, accessed 19 April 2023.

ADFVDRN (Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network) and ANROWS (Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety) (2022) Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network data report: intimate partner violence homicides 2010–2018 (2nd ed.; Research report 03/2022), ANROWS, accessed 21 July 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2021) Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2018, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 21 July 2023.

AIHW (2022a) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: interactive data on risk factor burden among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 21 July 2023.

AIHW (2022b) Australia’s mothers and babies, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 18 April 2023.

AIHW (2022c) Family, domestic and sexual violence data in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 24 July 2023.

AIHW (2023a) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework: summary report 2023, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 23 June 2023.

AIHW (2023b) Specialist homelessness services annual report 2022–23, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 13 February 2024.

AIHW (2024a) AIHW analysis of the National Hospital Morbidity Database.

AIHW (2024b) Child protection Australia 2022–23, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 18 July 2024.

AIHW (2024c) Specialist Homelessness Services Collection data cubes 2011–12 to 2022–23, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 13 February 2024.

ANROWS (2023) Aboriginal Families Study, ANROWS website, accessed 19 April 2023.

Backhouse C and Toivonen C (2018) National Risk Assessment Principles for domestic and family violence: companion resource. A summary of the evidence-base supporting the development and implementation of the National Risk Assessment Principles for domestic and family violence, ANROWS, accessed 29 March 2023.

Brown SJ, Glover K, Leane C, Gartland D, Nikolof A, Weetra D, Mensah F, Giallo R, Reilly S, Middleton P, Clark Y, Gee G and Rigney T (2021) Aboriginal Families Study Policy Brief 7: Health consequences of family and community violence, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, accessed 6 September 2023.

Closing the Gap Clearinghouse (2016) Family violence prevention programs in Indigenous communities, AIHW and Australian Institute of Family Studies, Australian Government, accessed 28 June 2023.

Coroners Court of Victoria (2023) Suicides of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, Victoria, 2018–2022, Coroners Court of Victoria, accessed 26 May 2023.

Cripps K (2023) Indigenous domestic and family violence, mental health and suicide, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 26 May 2023.

Cripps K and Davis M (2012) Communities working to reduce Indigenous family violence, Indigenous Justice Clearinghouse, accessed 16 May 2023.

Douglas H and Fitzgerald R (2018) ‘The Domestic Violence Protection Order system as entry to the criminal justice system for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’, International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 7(3):41–57, doi:10.5204/ijcjsd.v7i3.499.

DSS (Department of Social Services) (2020) A decade of data: findings from the first 10 years of Footprints in Time, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 24 July 2023.

DSS (2022) National plan to end violence against women and children 2022–2032, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 16 May 2023.

DSS (2023) Safe and Supported: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander First Action Plan 2023–2026, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 20 July 2023.

Fiolet R, Tarzia L, Owen R, Eccles C, Nicholson K, Owen M, Fry S, Knox J and Hegarty K (2021) ‘Indigenous perspectives on help-seeking for family violence: voices from an Australian community’, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(21–22):10128–10146, doi:10.1177/0886260519883861.

Haslam D, Mathews B, Pacella R, Scott JG, Finkelhor D, Higgins DJ, Meinck F, Erskine HE, Thomas HJ, Lawrence D and Malacova E (2023) The prevalence and impact of child maltreatment in Australia: Findings from the Australian Child Maltreatment Study: Brief Report, Australian Child Maltreatment Study, Queensland University of Technology, accessed 24 July 2023.

HREOC (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission) (1997 Bringing them home: Report of the national Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families, HREOC, accessed 6 February 2023.

HRSCSPLA (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs) (2021) Inquiry into family, domestic and sexual violence, Parliament of Australia, accessed 19 July 2023.

Kneebone LB (2015) Partner violence in the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC), DSS, Australian Government, accessed 24 July 2023.

Langton M, Smith K, Eastman T, O’Neill L, Cheesman E and Rose M (2020) Improving family violence legal and support services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women (Research report 25/2020), ANROWS, accessed 19 May 2023.

Miles H and Bricknell S (2024) Homicide in Australia 2022–23, AIC, accessed 2 May 2024.

National Office for Child Safety (2021) National Strategy to Prevent and Respond to Child Sexual Abuse 2021–2030, National Office for Child Safety, Australian Government, accessed 20 July 2023.

NIAA (National Indigenous Australians Agency) (2023a) Standalone First Nations National Plan, NIAA, Australian Government, accessed 28 August 2023.

NIAA (2023b) 2023 Commonwealth Closing the Gap Implementation Plan, NIAA, Australian Government, accessed 26 July 2023.

Our Watch (2018) Changing the picture: a national resource to support the prevention of violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children, Our Watch, accessed 23 June 2023.

Powell A, Flynn A and Hindes S (2022) Technology-facilitated abuse: national survey of Australian adults’ experiences, ANROWS, accessed 24 May 2023.

SNAICC (Secretariat of National Voice for our Children), National Family Violence Prevention Legal Services Forum and NATSILS (National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service) (2017) Strong families, safe kids: Family violence response and prevention for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and families, SNAICC website, accessed 19 April 2023.

Soldatic K, Sullivan CT, Briskman L, Leha J, Trewlynn W and Spurway K (2023) Indigenous LGBTIQSB+ people’s experiences of family violence in Australia, Journal of Family Violence, doi:10.1007/s10896-023-00539-1.

Victoria State Government (2019) Victorian Family Violence Data Collection Framework, Victoria State Government, accessed 21 July 2023.

Weetra D, Glover K, Buckskin M, Kit JA, Leane C, Mitchell A, Stuart-Butler D, Turner M, Yelland J, Gartland D and Brown SJ (2016) ‘Stressful events, social health issues and psychological distress in Aboriginal women having a baby in South Australia: implications for antenatal care’, BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16:88, doi:10.1186/s12884-016-0867-2.

WHO (World Health Organization) (2010) Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: Taking action and generating evidence, WHO, accessed 7 June 2023.

Willis M (2011) ‘Non-disclosure of violence in Australian Indigenous communities’, Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice no. 405, Australian Institute of Criminology.

- Previous page Key findings

- Next page Children and young people