Health outcomes

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

Key findings

- In 2021–22, 2 in 3 (67% or 496,000) women who had experienced sexual assault by a male perpetrator in the past 10 years reported they had felt anxiety or fear for their safety in the 12 months after their most recent incident of violence.

- In 2018, if no woman had experienced intimate partner violence, the disease burden among women due to homicide and violence would have been reduced by 46%.

Family, domestic and sexual violence can involve single and/or repeated traumatic experiences which impact victim-survivors’ health and wellbeing. The health outcomes can be serious and long-lasting, affecting an individual’s physical and mental health, which in turn can affect a person’s employment and education, relationships, and financial and housing stability.

This topic page focuses on the short-term, long-term, and permanent health outcomes among victim-survivors of FDSV, particularly intimate partner violence. While the reporting focuses on national quantitative data, some contributions from people with lived experience are included on this page to deepen our understanding. For other pages relating to the impacts and outcomes of FDSV, see also Behavioural outcomes, Economic and financial impacts and Domestic homicide.

What do we know?

Health outcomes associated with FDSV will vary in nature and extent depending on the type and severity of violence experienced. Some health outcomes are immediate, for example an injury, and some, such as mental illness, may develop over time and persist for many years after the violence has ceased (Loxton et al. 2017). For some people, ongoing or severe experiences of FDSV can lead to permanent disability, or death (On et al. 2016). However, with appropriate intervention, support and resources, these outcomes are preventable (WHO and PAHO 2012).

Evidence of the health outcomes associated with FDSV can inform the development of policy and service interventions that aim to improve outcomes for individuals experiencing violence.

This page includes information on mental health, injury and death, and sexual and reproductive health. For information on how FDSV may affect health behaviours, see Behavioural outcomes.

Some population groups may be at greater risk of experiencing FDSV and poorer health outcomes (see Population groups).

For information on behaviours and/or factors that may increase the likelihood of FDSV victimisation, see Factors associated with FDSV.

National data sources to measure health outcomes

Evidence of the health outcomes due to, or associated with, FDSV can be obtained using longitudinal surveys, cross sectional studies, burden of disease analysis and administrative data sets (such as hospital data).

Different types of data and research impact the questions that can be answered about health outcomes. For example, longitudinal studies follow the same individuals (that is, a cohort) over time to provide insight on the link between exposure (for example to FDSV) and subsequent outcome (for example, a mental health disorder). Cross sectional studies sample people at a point in time and can assist with measuring associations between 2 areas of interest (for example FDSV and health), however, they do not provide insight into the timing of events (for example, whether depression was experienced before or after experiences of FDSV). For more information, see How are national data used to answer questions about FDSV?.

- ABS Personal Safety Survey

- Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health

- AIHW Australian Burden of Disease Study

- AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database

For more information about these data sources, please see Data sources and technical notes.

Ten to Men: The Australian Longitudinal Study on Male Health is Australia’s first national longitudinal study that focuses exclusively on male health and wellbeing. Further analysis of the Ten to Men study can provide insights into the health and wellbeing of men who have experienced and/or perpetrated intimate partner violence. For more information about the Ten to Men study, please see the Data sources and technical notes.

What do the data tell us?

Burden of disease

Burden of disease refers to the quantified impact of living with and dying prematurely from a disease or injury. According to the 2018 Australian Burden of Disease Study (ABDS, see Box 1), child abuse and neglect contributed to 2.2% of the total disease burden and contributed to around 810 deaths (for more information on FDV during childhood see Children and young people). Among females, intimate partner violence (IPV) contributed to 1.4% of the total disease burden and contributed to around 230 deaths (AIHW 2021a).

The Australian Burden of Disease Study (ABDS) 2018 estimated the impact of various diseases, injuries and risk factors on total burden of disease for the Australian population. It combines health loss from living with illness and injury (non-fatal burden) and dying prematurely (fatal burden) to estimate total health loss (total burden).

The ABDS includes estimates of the contribution made by selected risk factors on the disease burden in Australia, including intimate partner violence (IPV) and child abuse and neglect. The disease burden due to IPV is currently only available for females, as there is not sufficient published research indicating a causal link between disease burden and the risk of IPV for males. The burden of disease analysis could be expanded in future studies to explore additional risk factors on violence.

National work on the health impact of violence

In 2020, the AIHW undertook a review of data sources for violence prevalence and a literature review on health outcomes of non-partner family violence and community violence.

The 2016 Personal Safety Survey was found to be the most suitable data source to estimate national prevalence of the various forms of violence. The literature review found:

- probable evidence that sexual violence may result in depressive disorders and anxiety disorders (specifically post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD)

- possible evidence that sexual violence may result in drug use disorders, alcohol use disorders and generalised anxiety disorder

- less convincing evidence for other types of violence (physical and emotional) and other health outcomes such as pre-term birth, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and diabetes.

There was inconclusive evidence on the association between perpetrator relationship and health outcomes.

Reporting of the risk factor sexual violence by any perpetrator with the health outcomes of anxiety disorders and depressive disorders may be considered for future ABDSs. Consideration may also be given to future exploratory work to include an experimental ‘total’ violence burden estimate which would combine the burden due to existing ABDS risk factors (IPV in women and child abuse and neglect).

Source: AIHW 2021a

For more information on how burden of disease is determined, see Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2018, Summary.

Diseases that were causally linked to IPV

The ABDS 2018 estimated the amount of burden that could have been avoided if no females aged 15 and over in Australia experienced IPV. In estimating this burden, 6 diseases were causally linked to exposure to intimate partner violence in females:

- depressive disorders (contributing to 15% of depressive disorders total burden in females)

- anxiety disorders (11%)

- early pregnancy loss (17%)

- homicide and violence (injuries due to violence) (46%)

- suicide and self-inflicted injuries (19%)

- alcohol use disorders (4%) (AIHW 2021b).

For example, if no women had experienced IPV in 2018 the disease burden among women due to homicide and violence would have been reduced by 46% (AIHW 2021b).

Diseases that were causally linked to child abuse and neglect

Child abuse and neglect was causally linked to:

- anxiety disorders (contributing to 27% of anxiety disorders burden)

- depressive disorders (20%)

- suicide and self-inflicted injuries (26%) (AIHW 2021b).

For more information on variation in burden attributable to intimate partner violence, and child abuse and neglect, by age and over time, see Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on risk factor burden.

For more information about health outcomes associated with child maltreatment, please see Children and young people.

Mental health

FDSV includes traumatic experiences which can affect an individual’s psychology and nervous system (trauma). This trauma can have short and/or long-term impacts on mental health, and cause behavioural changes (see Behavioural outcomes). Complex trauma, as a result of repeated and cumulative traumatic experiences, will usually have a greater impact on the individual; and childhood experiences of trauma are particularly damaging (RANZCP 2020).

Trauma may cause a range of health-related problems, including mental conditions, suicidality and self-harming behaviours; and the consequences of trauma can be intergenerational (RANZCP 2020). However, the relationship between FDSV and mental illness is complex, for example people with mental illness may have increased vulnerabilities that increase their risk of FDSV victimisation, and mental illness may develop or increase in severity as a result of FDSV victimisation (see Factors associated with FDSV). Recovery can take a lifetime and is unique to each person.

What does recovery mean to you?

'Recovery relates to one’s own sense of self, redefining boundaries, trusting your own judgement and capability, choosing to love and heal yourself. It is about making healthy choices and feeling empowered to do so. It includes mental, emotional and physical wellbeing and finding the right supports to manage ongoing impacts of trauma and other injuries that have resulted from the abuse.'

Lula

'You are never the same person after experiencing violence. Recovery is learning about the new version of yourself and navigating life while managing the ongoing impacts of the trauma. Recovery is learning to trust yourself and others again. This is often intertwined with recovering from poverty; recovering from being jobless and homeless.'

Lily

This section draws on national data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Personal Safety Survey (PSS) and the Australian Longitudinal Survey of Women’s Health (Box 2).

Anxiety or fear for personal safety due to violence

Partner violence

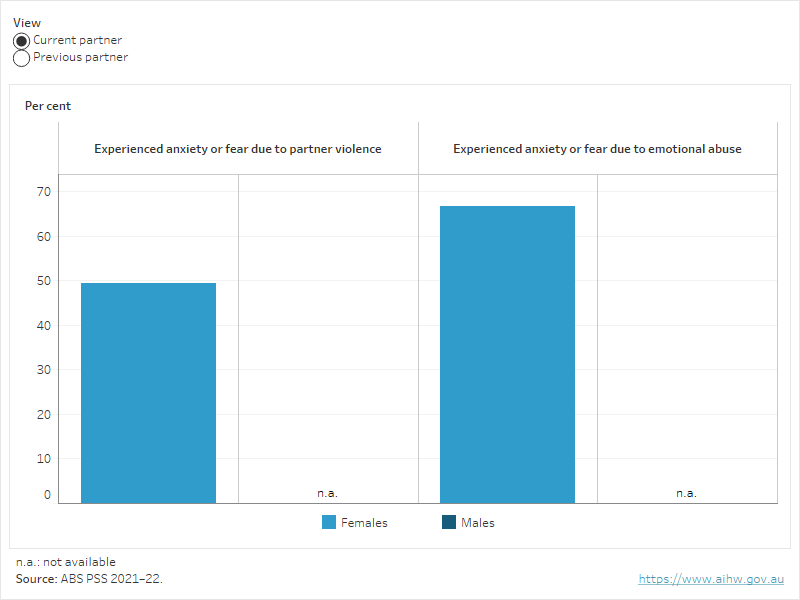

The ABS PSS collects data on the impacts of physical and/or sexual violence from a partner and/or emotional abuse from a partner. In 2021–22:

- the proportion of women who reported they had experienced anxiety or fear due to emotional abuse by a current partner was higher than for anxiety or fear due to partner violence

- when compared with men, a higher proportion of women reported they had experienced anxiety or fear due to violence by a previous partner and due to emotional abuse by a previous partner (ABS 2023a, Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proportion of people who experienced anxiety or fear due to experience of violence by a partner in their lifetime, by violence type, and current and previous partner, 2021–22

Figure 1 shows the proportion of males and females who had ever experienced anxiety or fear due to violence or emotional abuse from a current or previous partner.

Sexual violence

-

67%

of women in 2021–22 who had experienced sexual assault by a male perpetrator in the past 10 years had felt anxiety or fear for their safety in the 12 months after their most recent incident

Source: ABS Personal Safety Survey

Findings from the 2021–22 PSS estimated that more than 2 in 3 (67% or 496,000) women who had experienced sexual assault by a male perpetrator in the past 10 years reported they had felt anxiety or fear for their safety in the 12 months after their most recent incident of violence (ABS 2023b). Data for males are not available due to data limitations.

The Australian Longitudinal Survey of Women’s Health (ALSWH) is an ongoing longitudinal study of women’s health. The study began in 1996 and follows groups of women born in 1921–26, 1946–51, 1973–78 and 1989–95. The ALSWH collects information relevant to the health of women, including experiences of violence.

Some key findings from the data include:

- Women who had experienced sexual violence were more likely (than those who hadn’t) to report: a recent diagnosis of and/or treatment for depression; a recent diagnosis of and/or treatment for anxiety; high levels of stress; and high levels of psychological distress (Townsend et al. 2022).

- Depression was associated with childhood sexual abuse (Mishra et al. 2019)

- Women who had experienced domestic violence reported poorer mental health (that is, they were more likely to have felt that life was not worth living at some point in their lives) than those who had not experienced domestic violence (Mishra et al. 2019).

Injury

The 2018 ABDS identified IPV experienced by females as a significant risk factor for injury, associated with 7.2% of the total burden of injury (AIHW 2021a). National hospital data, drawn from the AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database, provide an indication of more severe and mostly physical injury cases due to FDV that have resulted in a person being admitted to hospital. They do not include presentations to emergency departments and only include assault hospitalisations where the perpetrator is coded as being a family member (including spouse or domestic partner). Hospital records can provide insight on the nature of the injury and how it occurred (for example, the type of force or weapon). For more information on FDV hospitalisations see Health services.

Around 3 in 4 hospitalisations for family and domestic violence injury were for females.

In 2022–23:

- around 3 in 4 (74%) hospitalisations for injury perpetrated by a spouse, domestic partner, parent or family member were for females

- around 9 in 10 (87%) hospitalisations for injury by a spouse or domestic partner were for females (AIHW 2024a).

Most partner assault of women involved bodily force

In 2022–23, almost 3 in 5 (59%, or 2,200) hospitalisations of women aged 15 years and older for assault by a spouse or domestic partner involved assault with bodily force. Almost 1 in 5 (19%, or 710) involved assault with either a blunt (13%) or sharp (6.6%) object, and 1 in 10 (10%, or 380) involved assault by hanging, strangulation and suffocation (AIHW 2024a).

For males, hospitalisations for assault by a spouse or domestic partner were most likely to involve injury from assault with a sharp object (41%, or 220 hospitalisations), followed by assault by bodily force (26%, or 135 hospitalisations) or with a blunt object (21%, or 115 hospitalisations) (AIHW 2024a).

Head and/or neck injuries are the most common injuries due to assault by a spouse or domestic partner

In 2022–23, almost 3 in 4 (72%, or 2,600) hospitalisations of women aged 15 years and older due to spouse or domestic partner assault involved injuries to the head and/or neck, including 435 (12%) hospitalisations for brain injury. Trunk injuries were more common among pregnant women (46%) than among women who were not pregnant (29%) (AIHW 2024a). For more information, see Pregnant people.

Of hospitalisations for males aged 15 years and older for assault by a spouse or domestic partner, 54% (or about 285) had a head and/or neck injury recorded, including 45 (8.5%) brain injuries. More than half (51%, or about 270) involved injury to limbs (shoulder, arm and/or hand) and 30% (or 160) had an injury to the trunk recorded (AIHW 2024a). (Note: a hospitalisation may have multiple injuries recorded and therefore proportions sum to more than 100%).

For more information about FDV hospitalisations, please see Health services, Children and young people and Pregnant people.

Separate analysis of linked hospital data over time showed that some individuals were hospitalised more than once for treatment and/or care after a FDV assault. Around 1 in 8 people with a FDV hospital stay during 2010–11 to 2017–18, had more than one FDV stay over a 9-year period (AIHW 2021c).

Sexual and reproductive health

Sexual and reproductive health outcomes associated with FDSV includes injury to reproductive organs, sexual dysfunction, gynaecological problems, sexually transmitted infections, abortion (medical and spontaneous) and birth complications. Additionally, violence can take the form of reproductive coercion (see Pregnant people). While both men and women can experience outcomes that affect their sexual and/or reproductive health, most available data are related to women. Additionally, national data on many of these health outcomes among people who have experienced FDSV are limited.

Data from the ALSWH showed that, when compared with women who had not experienced domestic violence, women who had experienced domestic violence were:

- more likely to be diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection, including human papillomavirus (HPV) (23% of women aged 22–27 in 2017, compared with 11%) (Loxton et al. unpublished in AIHW 2019)

- less likely to be screened for cervical cancer (75% of women aged 45–50 in 1996 and 53–58 in 2004 compared with 81%) (Loxton et al. 2009, in AIHW 2019).

Among more than 14,000 women aged 45–50 in 1996, women who had been diagnosed with cervical cancer were twice as likely to have experienced domestic violence, compared with women who had not been diagnosed with cervical cancer (29% versus 15%, respectively) (Loxton et al. 2009).

Women of childbearing age can experience increased risk of reproductive health and/or pregnancy outcomes. For more see Pregnant people and Mothers and their children.

Sexual health and dysfunction

Sexual violence may impact a victim-survivor’s sexual health and relationships. This violence can occur in the context of family violence, commonly intimate partner violence, or sexual violence by any perpetrator. Sexual violence may result in short-term injury directly related to an event, or longer-term impacts to sexual and reproductive function, whether that be physical, or psychological. However, it is important to note, not all people who experience sexual violence sustain physical trauma at the time of an event (Rees et al. 2011).

Health outcomes due to sexual violence can include, but are not limited to:

- damage to urethra, vagina and anus, and chronic pelvic pain

- gastrointestinal problems (including irritable bowel syndrome) and eating disorders

- sexually transmissible infections

- gynaecologic symptoms: for example, dysmenorrhea (severe pain or cramps in the lower abdomen during menstruation), menorrhagia (abnormally heavy or prolonged bleeding during menstruation) and problems associated with sexual intercourse (Rees et al. 2011).

Sexual dysfunction can occur in victim-survivors of sexual violence, particularly childhood sexual abuse. This may impact sexual function, satisfaction, and increase risk taking behaviours (Gewirtz-Meydan and Ofir-Lavee 2021). Currently, there is no national data available to indicate the prevalence of sexual dysfunction following sexual violence.

Deaths

Using data from the National Homicide Monitoring Program, the ABDS 2018 (see Box 1) estimated that intimate partner violence contributed to around 230 female deaths (or 0.3%) in 2018 (AIHW 2021a). Most of these deaths were due to homicide and violence, followed by suicide and self-inflicted injuries. For more information, on direct FDSV death outcomes, see Domestic homicide.

While homicides provide direct evidence of the permanent consequences of family and domestic violence, they underestimate the impact of family and domestic violence on mortality more broadly (or indirectly). IPV is a risk factor for a range of health outcomes which may increase a person’s risk of death, including by suicide or due to other means (On et al. 2016). Many studies have found strong associations between IPV and both suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts (Devries et al. 2013; Potter et al. 2021).

Family and domestic violence-related deaths by suicide

There is no nationally consistent collection of data for FDV-related deaths by suicide, although the Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network has indicated an intent to broaden their reporting to include FDV-related suicide deaths in the future (ADFVDRN) (Box 3). FDV-related deaths by suicide can occur among victim-survivors and perpetrators.

National data on suicide (intentional self-harm) is derived from information collected as part of the death registration process. Deaths must be certified by either a doctor, using the Medical Certificate of Cause of Death, or by a Coroner. Deaths from suicide are referred to a coroner and can take time to be fully investigated. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) collects information on all registered deaths from states and territories, and national data on suicide are reported annually (ABS 2021; AIHW 2023). For more information see Data sources and technical notes.

From these data, it is not possible to determine the extent or involvement of FDV in a death by suicide, however, information recorded on psychosocial risk factors can provide some insight on related factors. For example, in 2022, ‘Problems in relationship with spouse or partner’ was one of the most common risk factors for intentional self-harm, present in 14% of deaths by suicide for males and 12% for females. ‘Problems related to alleged sexual abuse of child by person within primary support group’ occurred in 4.1% of suicides of females aged under 25 years (AIHW 2024b).

The Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network (ADFVDRN) (the Network) was established in 2011 to analyse and share knowledge about deaths that occur in the context of family and domestic violence so as to improve service responses. The first stage of this work involved the development of a national minimum dataset for intimate partner homicides preceded by a reported or anecdotal history of violence between offender and victim (IPV homicides), with an intent to expand this to include homicides within a family relationship, ‘bystander’ homicides, and FDV-related suicides.

The dataset focuses on IPV homicides currently, and data on FDV-related suicide remains limited to suicide by offenders after homicide. In Australia, between 1 July 2010 and 30 June 2018, there were 45 cases where the offender of an IPV homicide died by suicide following the homicide.

For further discussion of the dataset and IPV homicides, see Domestic homicide.

Source: ADFVDRN and ANROWS 2022.

State and territory data

Some data on FDV-related suicides are available from some states and territories, however methods and definitions for defining a FDV-related suicide vary between the jurisdictions, and are not suitable for comparison. In some analysis, it is also not clear whether the person who has died by suicide was a victim or perpetrator of FDV.

- In New South Wales, there were 330 completed suicides between 1 July and 31 December 2013. Of these, 49% of the female suicides and 52% of the male suicides had a recorded or apparent history of domestic and family violence, relationship conflict or relationship breakdown (NSW DVDRT 2017).

- In Victoria, between 2009 and 2012 almost 35% of women who died by suicide had a reported history of family violence victimisation; around 50 deaths a year (CCV 2015).

- In Queensland, between July 2015 and 30 June 2021, 280 FDV-related suicide deaths were identified (DFVDRAB 2021).

- In Western Australia, there were 410 people who died by suicide between 1 January and 31 December 2017 – 68 of these people were women and children who were victims of family and domestic violence, including 20 children and young women (aged under 26 years) (Ombudsman Western Australia 2022).

- In Tasmania, a review identified characteristics of the 505 closed cases of death by suicide that occurred between January 2012 and December 2018. The review identified that 42% of people experienced conflict with their partner, and 19% experienced violence involving a partner that was considered a contributing stressor prior to their death. Additionally, 48% of people who died by suicide had ever experienced abuse or violence, however, available data do not specify whether the abuse was FDSV-related (Garrett and Stojcevski 2021).

An AIHW study investigated whether there were differences in the number of, and causes of death between people who had at least one family or domestic violence-related (FDV-related) hospital stay and people without a history of FDV-related hospital stays.

This study used longitudinal, national linked hospital and death data from the National Integrated Health Services Information Analysis Asset (NIHSI AA) from 2010–11 to 2018–19. People who had a FDV-related hospital stay (the FDV hospital cohort) were compared with a comparison group that had a hospital stay (but not a FDV hospital stay) in the same 9-year period, and matched on age, sex, Indigenous status, year of contact and remoteness area to assist with interpretation of the results.

The FDV hospital cohort had a higher rate of death and different causes of death compared with the comparison group. Between 2010 and 2019:

- 5.7% of the FDV hospital cohort died compared with 4.4% of the comparison group

- The FDV group were 10 times as likely to die due to assault, 3 times as likely to die due to accidental poisoning or liver disease, and 2 times as likely to die due to suicide, as the comparison group

- Almost 2 in 5 (39%) deaths among the FDV hospital cohort occurred before age 50, compared with fewer than 1 in 3 (31%) among the comparison group.

For more information on hospitalisations see Health services.

Source: AIHW 2021c.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2021) Causes of death, Australia, ABS website, accessed 10 February 2023.

ABS (2023a) Partner violence, ABS website, accessed 7 December 2023.

ABS (2023b) Sexual violence, ABS website, accessed 1 September 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2017) Behaviours & risk factors, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 November 2022.

AIHW (2019) Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 21 October 2022.

AIHW (2021a) Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2018, Australian Burden of Disease Study series no. 23, Cat. no. BOD 29, Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW (2021b) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on risk factor burden: Intimate partner violence, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 22 June 2022.

AIHW (2021c) Examination of hospital stays due to family and domestic violence 2010–11 to 2018–19, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 22 June 2022.

AIHW (2021d) Australian Burden of Disease Study: Methods and supplementary material 2018, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 2 March 2023.

AIHW (2023) Suicide & self-harm monitoring, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 23 February 2023.

AIHW (2024a) AIHW analysis of the National Hospital Morbidity Database.

AIHW (2024b) Psychosocial risk factors and deaths by suicide, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 9 July 2024.

ADFVDRN (Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network) and ANROWS (Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety) (2022) Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network Data Report: Intimate partner violence homicides 2010–2018 (2nd ed.; Research report 03/2022), ANROWS, accessed 8 August 2022.

Ayre J, Lum On M, Webster K, Gourley M and Moon L (2016) Examination of the burden of disease of intimate partner violence against women in 2011: Final report (ANROWS Horizons, 06/2016), ANROWS, accessed 8 August 2022.

CCV (Coroners Court of Victoria) (2015) Royal Commission into Family Violence: Response to Issues Paper, CCV, accessed 22 November 2021.

Coles J, Lee A, Taft A, Mazza D and Loxton D (2015) General practice service use and satisfaction among female survivors of childhood sexual abuse, Australian Family Physician, 44(1–2):71–6, accessed 5 June 2023.

Devries KM, Mak JY, Bacchus LJ (2013) ‘Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: a systematic review of longitudinal studies’, PLoS medicine, 10(5):e1001439, doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001439

DFVDRAB (Domestic and Family Violence Death Review and Advisory Board) (2021) Domestic and Family Violence Death Review and Advisory Board 2020–21 Annual Report, DFVDRAB, Queensland Government, accessed 27 September 2022.

Garrett A and Stojcevski V (2021) Report to the Tasmanian Government on suicide in Tasmania, Department of Justice, Tasmanian Government, accessed 29 November 2022.

Gewirtz-Meydan A and Ofir-Lavee S (2021) ‘Addressing sexual dysfunction after childhood sexual abuse: a clinical approach from an attachment perspective’, Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 47(1):43–59, doi:10.1080/0092623X.2020.1801543.

Loxton D, Powers J, Schofield M, Hussain R and Hosking S (2009) ‘Inadequate cervical cancer screening among mid-aged Australian women who have experienced partner violence’, Preventive Medicine, 48(2):184–188, doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.10.019.

Loxton D, Dolja-Gore X, Anderson AE and Townsend N (2017) ‘Intimate partner violence adversely impacts health over 16 years and across generations: a longitudinal cohort study’, PLOS One, accessed 22 February 2023.

Mishra G, Byles J, Dobson A, Chan H-W, Tooth L, Hockey R, Townsend N and Loxton D (2019) Policy briefs from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health Report prepared for the Australian Government Department of Health, February 2019, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 23 March 2023.

NSW DVDRT (2017) NSW Domestic Violence Death Review Team Report 2015-2017, DVDRT, Coroners Court New South Wales, accessed 18 September 2023.

On ML, Ayre J, Webster K and Moon L (2016) Examination of the health outcomes of intimate partner violence against women: State of knowledge paper, ANROWS, accessed 23 March 2023.

Ombudsman Western Australia (2022) Investigation into family and domestic violence and suicide, Ombudsman Western Australia, accessed 18 September 2023.

Potter LC, Morris R, Hegarty K, Garcıa-Moreno C and Feder G (2021) ‘Categories and health impacts of intimate partner violence in the World Health Organization multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence’, International journal of epidemiology, 50(2): 652–662, doi:10.1093/ije/dyaa220.

RANZCP (The Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists) (2020) Trauma-informed practice, RANZCP, accessed 22 March 2023.

Rees S, Silove D, Chey T, Ivancic L, Steel Z, Creamer M, Teesson M, Bryant R, McFarlane AC, Mills KL, Slade T, Carragher N, O’Donnell M and Forbes D (2011) ‘Lifetime prevalence of gender-based violence in women and the relationship with mental disorder and psychosocial function’, Journal of the American Medical Association, 306(5):513–512, doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1098.

Townsend N, Loxton D, Egan N, Barnes I, Byrnes E and Forder P (2022) A life course approach to determining the prevalence and impact of sexual violence in Australia: Findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, ANROWS, accessed 21 March 2023.

Vagi KJ, Rothman EF, Latzman NE, Tharp AT, Hall DM and Breiding MJ (2013) ‘Beyond correlates: a review of risk and protective factors for adolescent dating violence perpetration’, Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(4):633–649, doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9907-7.

WHO (World Health Organization) and PAHO (Pan American Health Organization) (2012) Understanding and addressing violence against women, WHO, accessed 1 November 2022.

- Previous page Key findings

- Next page Behavioural outcomes