Domestic homicide

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

Key findings

- One woman was killed every 11 days and one man was killed every 91 days by an intimate partner on average in 2022–23.

- Intended or actual separation are risk factors for intimate partner homicide.

- The intimate partner homicide victimisation rate decreased (from 0.66 to 0.18 per 100,000) between 1989–90 and 2022–23.

Some family and domestic violence incidents are fatal. Intimate partner homicide is the most common form of domestic and family homicide with the majority involving a female victim. Domestic and family homicides rarely occur without warning and in many instances there have been identifiable risk factors and repeated episodes of abuse prior to the homicide (ADFVDRN and ANROWS 2022).

Understanding the prevalence of family and domestic homicide, its nature and risk factors can allow us to better identify people at higher risk and design and assess the policies and programs that aim to prevent domestic homicide.

What is domestic homicide?

Domestic homicide refers to the unlawful killing of a person in an incident involving the death of a family member or other person in a domestic relationship, including people who have a current or former intimate relationship.

Domestic homicide is defined differently by the criminal law of each Australian state and territory, with some differences in how each defines or determines offender intent and responsibility and the severity of the crime (ABS 2018). Generally, homicide can include:

- Murder – an unlawful killing where there is intent to kill, intent to cause grievous bodily harm with the knowledge that it was probable that death or grievous bodily harm would occur, and/or no intent to kill but it occurs while committing a crime.

- Manslaughter – an unlawful killing while deprived of the power of self-control by provocation, or under circumstances amounting to diminished responsibility or without intent to kill, as a result of a careless, reckless, negligent, unlawful or dangerous act (other than the act of driving) (ABS 2023c).

Data sources for measuring domestic homicide

This report includes homicide data from 3 main sources – Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) National Homicide Monitoring Program (NHMP), ABS Recorded Crime – Victims and the Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network (ADFVDRN). For more information about these data sources, please see Data sources and technical notes.

There are differences in the scope, collection methods and criteria for identifying a family or domestic violence homicide between these data sources, see Box 1.

The scope, collection methods and criteria for identifying a family or domestic violence homicide differ between data sources. These collections are not directly comparable but complement each other as statistical sources.

AIC National Homicide Monitoring Program

Data for the NHMP are derived from both police records and coronial records (Miles and Bricknell 2024). The NHMP also undergoes a quality control process that involves cross referencing and supplementing data with additional material from court documents. The NHMP collects information on homicides. This topic page uses the NHMP for domestic homicide prevalence data from 1989–90 to 2022–23. The homicide classification used here is based on the closest relationship between the victim and primary offender. Domestic homicides include homicides where the relationship of the victim to the offender was:

- an intimate partner – victim and offender are current or former partners (married, de facto, boyfriend/girlfriend and so on)

- a child

- a parent

- a sibling

- an other family member – any other family relationship including nephew/niece, uncle/aunt, cousins, grandparents and kinship groups.

Family relationships include biological, adoptive, foster and kinship care, and step relatives. In this topic page these relationships have been further grouped into intimate partner homicides and family member homicides (all domestic homicides excluding intimate partner homicides).

ABS Recorded Crime – Victims

Data for the ABS Recorded Crime – Victims collection (the ABS collection) are derived from police records and compiled according to the National Crime Recording Standard to maximise consistency between states and territories (ABS 2023c). As these data are processed differently to the NHMP, these 2 data sources are not directly comparable. The ABS collection includes information on homicides and related offences (including murder, attempted murder and manslaughter). This report uses the ABS collection data for 2022 to present further information on homicides and attempted murder to complement NHMP prevalence data. In the ABS collection, family and domestic violence (FDV) related data are derived from 2 variables: an FDV flag recorded by police officers and through known relationship information. FDV related offences include the following relationships:

- partner (spouse, husband, wife, boyfriend, and girlfriend)

- ex-partner (ex-spouse, ex-husband, ex-wife, ex-boyfriend, and ex-girlfriend)

- parent (including step-parents)

- other family member (including, but not limited to, child, sibling, grandparent, aunt, uncle, cousin, niece, nephew)

- other non-family member (carer, guardian, kinship relationships) (ABS 2023c).

Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network

Data used by the ADFVDRN in their reporting are derived from case reviews, coronial records, and police and media reports (ADFVDRN and ANROWS 2022). Unlike the NHMP and ABS Recorded Crime – Victims collection, the ADFVDRN only includes data on intimate partner homicides preceded by a reported or anecdotal history of domestic violence between offender and victim (IPV homicides). The ADFVDRN defines domestic violence to include behaviours such as physical assault, sexual assault, threats, intimidation, psychological and emotional abuse, social isolation and economic deprivation. The ADFVDRN developed a first-stage National Minimum Dataset (NMDS) to examine national trends and patterns related to intimate partner homicides.

The ADFVDRN worked together with ANROWS to report data from the NMDS on about 310 cases of IPV homicides between July 2010 and June 2018 including data about the primary abuser, as identified from reported and anecdotal accounts of abuse in the relationship between IPV homicide offenders and victims (see Data sources and technical notes). A focused dataset (containing about 290 cases) allowed further analysis of characteristics such as domestic violence orders and separations (see Data sources and technical notes) (ADFVDRN and ANROWS 2022).

What do we know?

Existing data suggests that females are disproportionately the victims of intimate partner and domestic homicide around the world. A United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime report estimated that globally, while 81% of all homicide victims are males, 82% of intimate partner homicide victims are female and 64% of intimate partner/family-related homicide victims are female (UNODC 2019). It was also estimated that around 1 in 3 (34%) women intentionally killed worldwide are killed by an intimate partner, however, there are large differences across regions. Oceania (which includes Australia) had the highest estimated proportion of women killed exclusively by intimate partners (42%) and Europe had the lowest (29%) (UNODC 2019).

Risk factors for domestic homicide

Much of the national and international research on domestic homicide offenders has focused on identifying common characteristics of homicide offenders, their relationships and other factors that could relate to an increased likelihood of committing homicide (risk factors), particularly for intimate partner homicide. Some of the individual- and relationship- level risk factors for intimate partner homicide are:

- history of sexual violence by the homicide offender (Spencer and Stith 2020)

- history of non-fatal strangulation of the victim by the offender (Glass et al. 2008)

- offender mental and physical health problems, particularly depression and suicidal ideation (Lysell et al. 2016; Boxall et al. 2022; Lawler et al. 2023)

- offender has experienced traumatic life events including war, homelessness, incarceration, abuse and neglect as a child, and the death of significant family members (Kivisto 2015; Boxall et al. 2022)

- separation between victim and offender (Dobash and Dobash 2011; Spencer and Stith 2020; Boxall et al. 2022)

- offender’s jealousy and perception of violations to gendered norms (such as a victim dedicating herself to a career or refusing to submit to the offender) (Dobash and Dobash 2011; Kivisto, 2015; Boxall et al. 2022).

While there may be an association between these risk factors and cases of intimate partner homicide, this does not mean any one factor or combination cause the homicide. For example, while people with depression are over-represented among perpetrators of intimate partner homicide, a recent study found depression alone holds limited explanatory value for understanding intimate partner homicide and should be considered in the context of co-occurring risk factors (Lawler et al. 2023).

Pathways into and intervention strategies for intimate partner homicide

A recent report by the AIC identified three main pathways into which the majority of male-perpetrated homicides of a female intimate partner in Australia could be classified (see Box 2). This study identified a number of intervention points and strategies that may reduce male-perpetrated female intimate partner homicide including:

- through the use of evidence-based intimate partner violence intervention programs in and out of criminal justice settings

- integrating intimate partner violence intervention programs with alcohol and other drug programs and mental health services

- investment in frontline staff education and identification of coercive control with an emphasis on treating identified cases seriously

- improved identification of high-risk victims and targeted and timely responses to protect them (including through safety planning around domestic violence orders)

- investment in new techniques to detect and monitor potential homicide offenders (intelligence-led approaches such as the use of GPS data, online activity data, mental health data, family law process information, and so on) (Boxall et al. 2022).

The AIC report, The “Pathways to intimate partner homicide” project: Key stages and events in male-perpetrated intimate partner homicide in Australia, identified three main pathways of male-perpetrated homicide of a female intimate partner by analysing 199 incidents between 1 July 2007 and 30 June 2018 for patterns in the sequence of events, interactions and relationship dynamics preceding and coinciding with the homicide:

- The fixated threat pathway (33% of cases) typically involves successful middle-class men who have power over their partner (for example, difference in age, income, and so on) and use abusive and controlling behaviours but have little justice system contact. Upon a loss of control (e.g. through separation), violence escalates and the homicide often involves planning. In these cases the offender typically pleads not guilty.

- The persistent and disorderly pathway (40% of cases) involves offenders with complex histories of trauma, co-occurring mental and physical health problems, significant histories of violence towards partners and others, and justice system contact (including protection orders). The homicides are often similar to previous instances of violence in the relationship but involve additional risk factors such as heavy alcohol use or isolation. Separation is relatively rare in these cases.

- The deterioration/acute stressors pathway (11% of cases) involves offenders who are in long-term, non-abusive relationships with low levels of, or an absence of, violence or justice system contact. Substantial life stressors result in the onset or exacerbation of mental and physical health problems for the offender and trigger increased conflict in the relationship. The homicides are often during an argument, and the result of a nearly instantaneous decision to harm the victim. Offenders are likely to demonstrate remorse and plead guilty (Boxall et al 2022).

The remaining cases involved: overlapping features of the three pathways (15%) or were considered outliers due to unique circumstances (1.5%) (Boxall et al 2022).

What do the data tell us?

-

1 woman was killed every 11 days

1 man was killed every 91 days

by an intimate partner on average in 2022–23

Source: AIC National Homicide Monitoring Program

Domestic homicide victims made up over one-third (38% or 84) of all homicide victims (around 220 victims) in 2022–23 in the National Homicide Monitoring Program (NHMP) (Miles and Bricknell 2024).

The majority of domestic homicide victims are killed by an intimate partner.

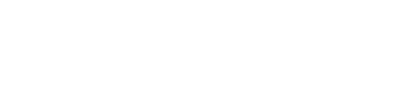

Of the 84 domestic homicide victims in 2022–23:

- 38 were killed by an intimate partner

- 46 were killed by a family member with:

- 16 killed by a parent

- 16 killed by a child

- 4 killed by a sibling

- 10 killed by a family member other than child, parent or sibling (Miles and Bricknell; Figure 1).

Figure 1: Domestic homicide victims, by relationship with offender and sex, 2022–23

Figure 1 shows the proportion and number of domestic homicide victims by victim relationship with the offender and the sex of the victim.

More females than males are victims of domestic homicide.

There were 46 female domestic homicide victims and 38 male victims in 2022–23. Among these:

- most females were killed by an intimate partner – 3 in 4 female victims (74%), with about 1 in 10 males killed by an intimate partner (11%)

- most males were killed by a parent – 1 in 3 male victims (34%), with about 1 in 15 females killed by a parent (6.5%) (Figure 1).

Of the 135 victims of family and domestic violence homicides and related offences in 2022 in the ABS Recorded Crime – Victims data collection:

- 71 were victims of murder, with 35 female victims and 34 male victims

- 42 were victims of attempted murder, with twice as many females as males (29 compared with 13)

- 14 were victims of manslaughter, with similar numbers of female and male victims (ABS 2023a).

There were 41 recorded intimate partner homicides and related offences in Australia (excluding data from Western Australia) in 2022, with about 3 times as many females (28) as males (11) (see Data sources and technical notes) (ABS 2023b).

Note that values from the ABS Recorded Crime – Victims data collection have been randomly adjusted to avoid the release of confidential data. Component items may not sum to totals.

Characteristics of intimate partner homicides that had a history of domestic and family violence

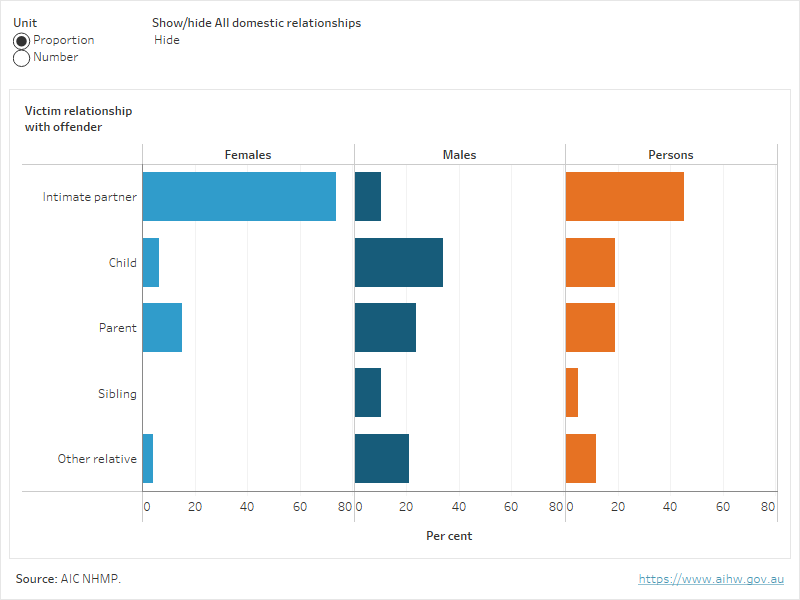

Among about 310 IPV homicides between July 2010 and June 2018 that were included in the ADFVDRN IPV homicide dataset, the majority involved a male killing a current or former partner:

- about 4 in 5 (77%) involved a male killing a current or former female partner

- about 1 in 5 (21%) involved a female killing a male partner

- about 1 in 20 (1.9%) involved a male killing a male partner

- no cases involved a female killing a female partner (ADFVDRN and ANROWS 2022).

In most IPV homicides a male is the primary domestic violence abuser.

A male was most commonly the primary domestic violence abuser in the relationship, including when a female killed a male partner (see Data sources and technical notes). The male was the primary abuser:

- in the vast majority (95%) of cases where a male killed a female partner

- in about 7 in 10 (71%) cases where a female killed a male partner (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Domestic violence perpetration/victimisation status in IPV homicides, July 2010 to June 2018

Figure 2 shows the number of IPV homicide incidents in which either the victim or offender were the primary domestic violence abuser or if both used domestic violence against each other.

Emotional and psychological abuse, and physical abuse were the most common forms of abuse leading up to IPV homicides where a male primary abuser killed a female partner.

In the IPV homicide dataset, among cases where a male primary abuser killed a female partner (about 210), the most common forms of abuse used in the relationship were emotional and psychological abuse (82%), and physical abuse (80%). Other common forms of abuse included:

- social abuse (63%)

- financial abuse (27%)

- sexual abuse (16%) (ADFVDRN and ANROWS 2022).

As multiple forms of abuse could be recorded for each case, proportions will not sum to 100%.

Among cases where a male primary abuser killed a female partner, the male abuser stalked the female victim in about 2 in 5 (42%) cases. This could occur both during the relationship (33%) and/or after the relationship (21%). See Stalking and surveillance for more information on the prevalence and effects of stalking.

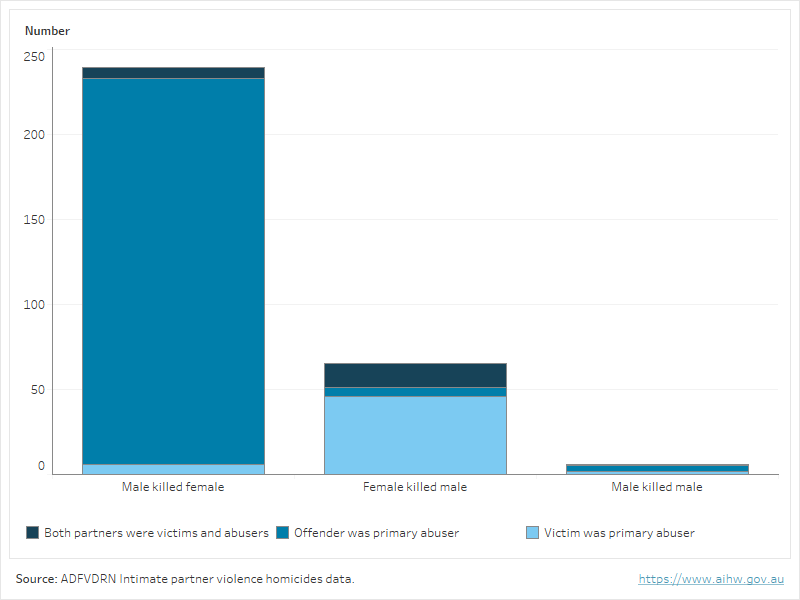

A current domestic violence order was in place in about 1 in 5 (22%) IPV homicides where a male killed a female.

Domestic violence orders (current or historical) were held in over 2 in 5 (43%) cases where a male killed a female intimate partner in the ADFVDRN focused dataset (about 225 cases) (see Box 1 for definition):

- In about 1 in 5 (22%) cases there was a current domestic violence order, with the majority of these (90%) naming the female victim as the protected person.

- In 3 in 10 (30%) cases there was a historical domestic violence order, with most of these (79%) naming the female victim as the protected person (Figure 3).

Figure 3: IPV homicide victims where historical or current domestic violence orders (DVO) were in place, July 2010 to June 2018

Figure 3 shows the number of IPV homicide cases in which either the victim or offender or both were protected by a current or historical domestic violence order.

Domestic violence orders (current or historical) were held in two-thirds (66%) of the cases where a female killed a male intimate partner (about 60):

- In about 1 in 3 (34%) cases there was a current domestic violence order, with over half of these (57%) naming the female homicide offender as the protected person.

- In about 1 in 2 (47%) of cases there was a historical domestic violence order, with over half of these (59%) naming the female homicide offender as the protected person (Figure 3).

It is possible that while a person is identified as the protected person in a domestic violence order, they may still be the primary abuser. Determining the person most in need of protection in domestic violence orders can be complex and instances where the legal system has been manipulated by an abuser to exert power over a victim (systems abuse) have occurred (AIJA and AGD 2022). As systems abuse is not explored or captured in the ADFVDRN dataset, it is important to keep this complexity in mind when interpreting data related to who is protected by a domestic violence order. For more information on the number of domestic violence orders, see Legal systems.

In more than 2 in 5 (43%) IPV homicide cases the children of homicide offenders and victims were exposed to violence between their parents.

In more than 2 in 5 (43%) IPV homicide cases children were exposed to the violence between their parents/caregivers. The IPV homicide offenders and victims were joint parents of about 170 children aged under 18 at the time of the homicide. Eight children were killed during the homicide (ADFVDRN and ANROWS 2022). For more information on children exposed to family, domestic and sexual violence, see Children and young people.

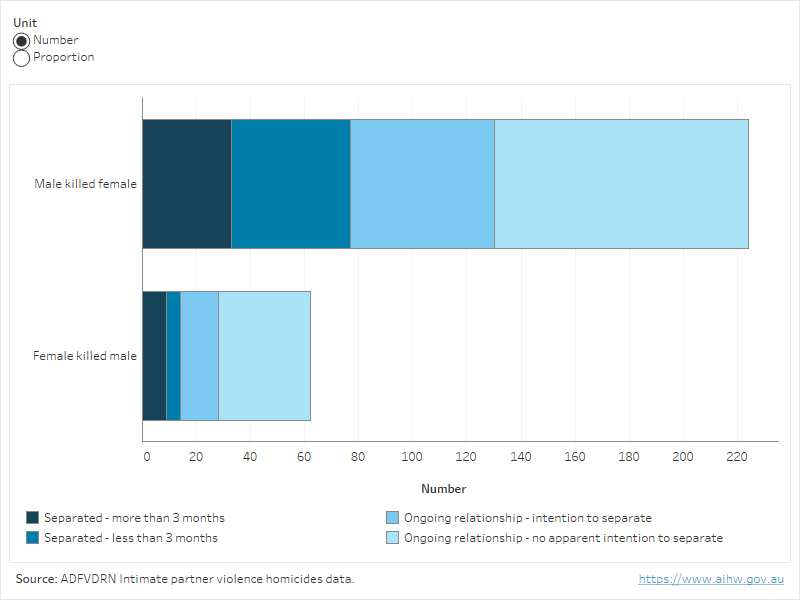

Female IPV homicide victims are more likely to be killed during a period of intended or actual separation.

In about 3 in 5 (58%) of the cases where a male killed a female partner in the ADFVDRN focused dataset (about 225), one or both partners intended to separate or they had separated at the time of the homicide (see Box 1 for definition):

- In about 1 in 3 (34%) cases the couple was separated, with almost 3 in 5 of these cases involving a separation within the past 3 months (57% of separated couples).

- In about 1 in 4 (24%) cases the couple were in an ongoing relationship where at least 1 person had expressed their intention to separate, with the majority (94%) of these cases involving the female victims intention (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Relationship status at the time of IPV homicide, July 2010 to June 2018

Figure 4 shows the number of IPV homicide cases in which the offender and victim were separated, intended to separate or had no apparent intention to separate at the time of the IPV homicide.

Among the 62 IPV homicide cases where a female killed a male partner in the ADFVDRN focused dataset, intended or actual separation was present in less than half (45%):

- In about 1 in 4 (23%) cases men were separated, with about 1 in 3 (36%) of these cases involving a separation in the past 3 months.

- In about 1 in 4 (23%) cases one or both parties intended to separate, with the female offender being the one intending to separate in about 3 in 5 (57%) of these cases (Figure 4).

Note that values may not add to totals due to rounding.

Only just over one-third (36%) of IPV homicide victims and offenders were in formal, paid employment.

Workplaces can be an important site of intervention and prevention for FDV for both victims and perpetrators. However, only just over one-third (36%) of all IPV homicide offenders and victims were engaged in formal, paid employment at the time of the homicide in the ADFVDRN IPV homicide dataset (ADFVDRN and ANROWS 2022).

3 in 5 (60%) IPV homicide offenders had problematic drug and/or alcohol use before or at the time of the homicide.

Three in 5 (60%) IPV homicide offenders engaged in problematic drug and/or alcohol use in the lead up to and/or at the time of the homicide in the ADFVDRN IPV homicide dataset. This was similar for both male offenders (61%) and female offenders (58%) (ADFVDRN and ANROWS 2022).

This represents a pattern of behaviour and possible site of intervention but does not identify problematic substance use as a causative factor for IPV homicide (ADFVDRN and ANROWS 2022).

Has it changed over time?

-

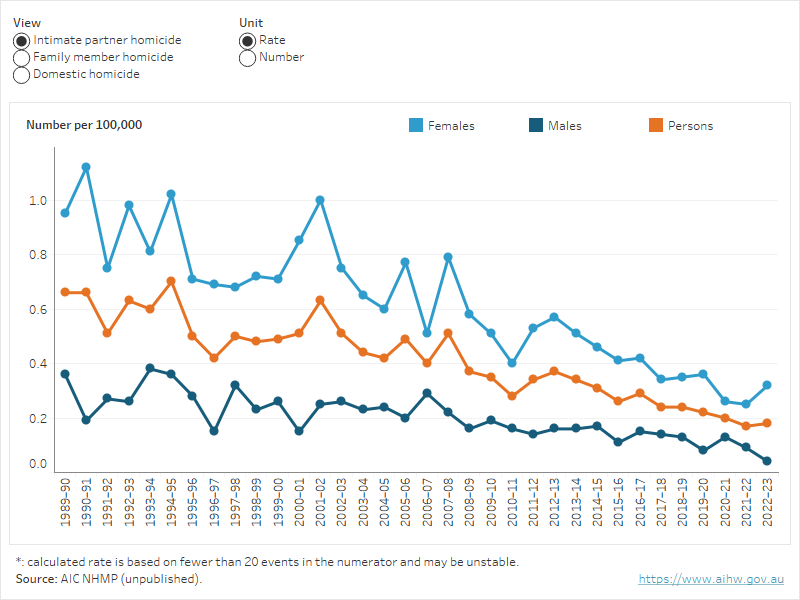

The intimate partner homicide victimisation rate decreased from 0.66 to 0.18 per 100,000 between 1989–90 and 2022–23

Source: AIC National Homicide Monitoring Program

The domestic homicide victimisation rate decreased from 0.74 to 0.32 per 100,000 people between1989–90 and 2022–23 in the NHMP:

- The female victimisation rate decreased from 0.90 to 0.34 per 100,000 females.

- The male victimisation rate decreased from 0.59 to 0.29 per 100,000 males (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Domestic homicide victims, by sex, 1989–90 to 2022–23

Figure 5 shows the number of domestic homicide victims and victimisation rate by sex over time including changes in intimate partner homicide victims and family homicide victims.

The intimate partner homicide victimisation rate decreased (from 0.66 to 0.18 per 100,000 people aged 18 years and over) between 1989–90 and 2022–23:

- The female victimisation rate has consistently been more than twice as high as the male victimisation rate (with the exception of 2006–07 when the rate was just under twice as high).

- The victimisation rate decreased for both females (from 0.95 to 0.32 per 100,000) and males (from 0.36 to 0.04 per 100,000) (Figure 5).

A 25% reduction per year in female victims of intimate partner homicide is an identified target in the Outcomes Framework 2023-2032. For related data, see the National Plan Outcomes and the AIC Intimate partner homicide dashboard (which also includes preliminary quarterly updates).

The family member homicide victimisation rate decreased (from 0.26 to 0.17 per 100,000 people) between 1989–90 and 2022–23. The male victimisation rate has generally been higher than the female victimisation rate over time. In 2022–23, the rate for males and females was 0.26 and 0.09 per 100,000, respectively (Figure 5).

According to data from the ABS Recorded Crime – Victims data collection, from 2014 to 2022, the recorded victimisation rate for:

- family and domestic violence homicide and related offences decreased from 0.7 to 0.5 per 100,000 people

- intimate partner homicide and related offences decreased from 0.3 to 0.2 per 100,000 people (excluding data from Western Australia) (see Data sources and technical notes) (ABS 2023a, 2023b).

Is it the same for everyone?

People of all ages and backgrounds can be victims of domestic homicide. However, some people are at a greater risk than others.

Based on the latest available report on the demographic features of Australian domestic homicide victims using NHMP data (see Box 1), between 1 July 2002 and 30 June 2012, the most common age groups when homicide occurred varied by homicide type:

- for intimate partner homicides, about 2 in 5 (39%) victims were aged 35–49

- for filicide (a parent killing a child), around 1 in 2 (51%) victims were aged 1–9

- for parricide (a child killing a parent), around 2 in 5 (38%) victims were aged 65 and over

- for siblicide (a sibling killing a sibling), over 1 in 3 (35%) victims were aged 35–49

- for homicides involving other family members, about 1 in 5 (23%) victims were aged 35–49 (Cussen and Bryant 2015).

Demographic features of IPV homicide offenders and victims

Among intimate partner homicides preceded by a reported or anecdotal history of violence between offender and victim (IPV homicides) in the ADFVDRN IPV homicide dataset (about 310), differences are apparent for:

- Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people, who were disproportionately represented in IPV homicide offenders (27%) and victims (27%) compared with their representation in the general population (3.2%) (ABS 2022a; ADFVDRN and ANROWS 2022).

- People with disability, who were under-represented in IPV homicide offenders (9.6%) and victims (7.1%) compared with their representation in the general population (18%) (ABS 2019; ADFVDRN and ANROWS 2022).

People known to be born overseas had a similar representation among IPV homicide offenders (28%) and victims (26%) compared to their representation in the general population (29%) (ABS 2022b; ADFVDRN and ANROWS 2022).

Values presented give an indication of differences rather than the true number of homicide offenders and victims from specific population groups, see Data sources and technical notes.

For further information on family, domestic and sexual violence related to population groups, see Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, People with disability and People from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

ABS (2018) 4533.0 – Directory of family, domestic, and sexual violence statistics, 2018, ABS website, accessed 14 June 2023.

ABS (2019) Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: Summary of findings, ABS website, accessed 14 June 2023.

ABS (2022a) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: Census, ABS website, accessed 14 June 2023.

ABS (2022b) Australia’s population by country of birth, ABS website, accessed 14 June 2023.

ABS (2023a) Recorded Crime – Victims, ABS website, accessed 14 June 2023.

ABS (2023b) Recorded Crime – Victims, 2021, customised request, ABS.

ABS (2023c) Recorded Crime – Victims methodology, ABS website, accessed 14 June 2023.

ADFVDRN (Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network) and ANROWS (Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety) (2022) Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network Data Report: Intimate partner violence homicides 2010–2018 (2nd ed.; Research report 03/2022), ANROWS, accessed 14 June 2023.

AIC (Australian Institute of Criminology) (2024) National Homicide Monitoring Program 1989–90 to 2022–23, customised request, AIC.

AIJA (Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration) and AGD (Attorney-General’s Department) (2022) National Domestic and Family Violence Bench Book – Systems abuse, AIJA and AGD, accessed 14 June 2023.

Boxall H, Doherty L, Lawler S, Franks C and Bricknell S (2022) The “Pathways to intimate partner homicide” project: Key stages and events in male-perpetrated intimate partner homicide in Australia (Research report 04/2022), ANROWS, accessed 14 June 2023.

Cussen T and Bryant W (2015) Domestic/family homicide in Australia, AIC, accessed 14 June 2023.

Dobash RE and Dobash RP (2011) What were they thinking? Men who murder an intimate partner, Violence Against Women, 17(1):111–134, doi:10.1177/1077801210391219.

Glass N, Laughon K, Campbell J, Block CR, Hanson G, Sharps PW and Taliaferro E (2008) Non-fatal strangulation is an important risk factor for homicide of women, Journal of Emergency Medicine, 35(3):329–335, doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.02.065.

Kivisto AJ (2015) ‘Male perpetrators of intimate partner homicide: A review and proposed typology’, Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 43(3):300–312.

Lawler S, Boxall H and Dowling C (2023) The role of depression in intimate partner homicide perpetrated by men against women: An analysis of sentencing remarks, AIC, accessed 14 June 2023.

Lysell H, Dahlin M, Långström N, Lichtenstein P and Runeson B (2016) Killing the mother of one’s child: Psychiatric risk factors among male perpetrators and offspring health consequences, Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(3):342–347 doi:10.4088/JCP.14m09564

Miles H and Bricknell S (2024) Homicide in Australia 2022–23, AIC, accessed 2 May 2024.

Spencer CM and Stith SM (2020) Risk factors for male perpetration and female victimization of intimate partner homicide: A meta-analysis, Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(3):527–540, doi:10.1177/1524838018781101.

UNODC (The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime) (2019) Global Study on Homicide 2019, UNODC, accessed 14 June 2023.

- Previous page Behavioural outcomes

- Next page Economic and financial impacts