Financial support and workplace responses

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

Key findings

Support may be provided to both victim-survivors and perpetrators of family, domestic and sexual violence (FDSV), through financial support and/or through supports for employees in the workplace. Financial support can include financial assistance (such as one-off payments to help a person leave a violent relationship) and financial advice and planning (to help a person establish independence). In general, these responses are intended to provide assistance in the short- or long-term, to reduce the economic and financial impacts of violence.

Workplaces can also respond to FDSV by providing support to employees. These supports may be accessed in the form of leave entitlements or through employee assistance programs. Some workplaces may also have organisation-specific policies or mechanisms to respond to violence that occurs in the workplace.

This topic page looks at the financial supports available for those who have experienced violence and a range of workplace responses.

What do we know?

Family and domestic violence (FDV) is the main reason women and children leave their homes in Australia. Victim-survivors of FDV who are leaving violent situations, are often faced with the substantial cost of leaving the home. These costs can include deposits, rental bonds and items for a new home; legal and medical costs; travel or moving costs; and for mothers, providing for their children (AHURI 2021; HRSCSPLA 2021). These costs may prevent women from leaving an abusive relationship and may be a reason women return to a previous violent partner (HRSCSPLA 2022). Financial implications have been reported by single mothers as a reason for returning to a previous violent partner following a temporary separation. This is a choice many women face when they experience violence – the choice between staying in a violent situation or poverty (see Economic and financial impacts for more detail).

A range of services are designed to provide immediate support to people who have to leave their home due to violence, including crisis payments and accommodation (see also Services responding to FDSV). Some services are designed to provide longer-term financial support, in the form of training courses, financial planning and advice, so that victim-survivors can become more independent and economically secure.

Some victim-survivors of violence may also receive financial support in the form of payments or loans from services not specific to FDSV, such as emergency relief services, however these broader services are not in scope for this topic.

Workplaces can also respond to FDSV by providing access to supports, and by working directly with victim-survivors and/or perpetrators, to provide counselling or advice, or by implementing initiatives that improve workplace safety and/or support employees experiencing violence.

What data are available to report on financial and workplace support?

Data are available from Services Australia about Crisis payments designed to support those who have experienced violence. Data are also available from a number of sources about workplace specific initiatives that respond to violence (such as the Workplace Agreements Database and Workplace Gender Equality Agency data). For more information about these data sources, please see Data sources and technical notes.

What do the data tell us?

Financial support

Crisis Payment for extreme circumstances family and domestic violence

-

Between 2015–16 and 2022–23, the number of claims granted for family and domestic violence Crisis Payments increased by about 60%

Source: Services Australia customer data

People who are in severe financial hardship and have experienced changes in their living arrangements due to family and/or domestic violence, and are receiving, or are eligible to receive, an income support payment or ABSTUDY Living Allowance (see Box 1), may receive a one-off Crisis Payment. This payment is paid in addition to a person's income support payment (Services Australia 2023).

Income support payment: A sub-category of benefits paid by the Australian Government which are regular payments that assist with the day-to-day costs of living.

ABSTUDY Living Allowance: A fortnightly payment by the Australian Government to help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians with living costs while studying or training.

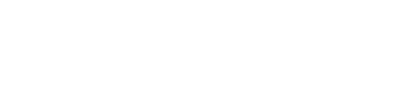

Between 2015–16 and 2022–23, the number of claims granted increased by about 60% (17,400 to 27,700). The proportion of income support recipients who received at least one family and domestic violence Crisis Payment each year increased slightly from 0.34% to 0.56% (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Claims granted for family and domestic violence Crisis Payments by gender, 2015–16 to 2022–23

The interactive visualisation shows the number of family and domestic violence Crisis Payment claims granted per year from 2015–16 to 2022–23, and as a proportion of all income support recipients.

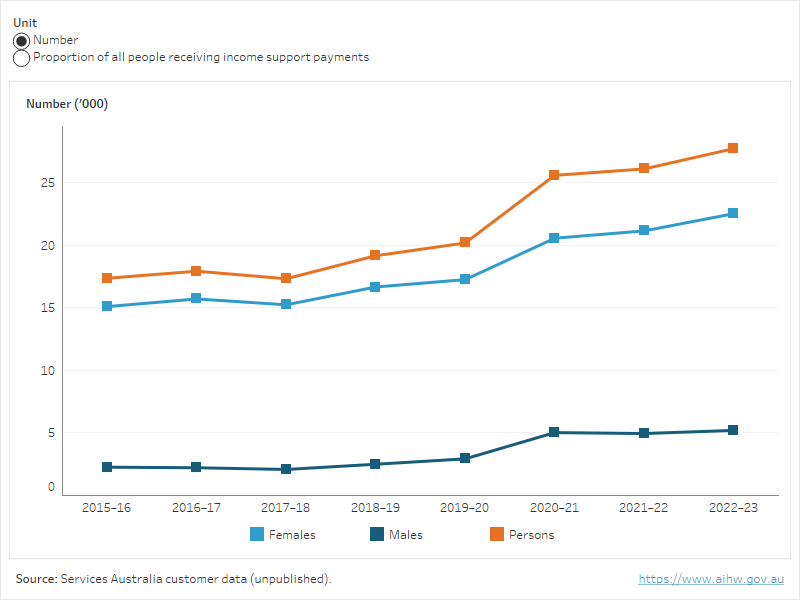

Data are also available for the number of family and domestic violence Crisis Payment claims granted per year by gender and sub-category of Crisis Payment. Between 2015–16 and 2022–23, the most common sub-category of family and domestic violence Crisis Payment each year was Victim left home, regardless of gender (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Claims granted for family and domestic violence Crisis Payments by gender and sub-category, 2015–16 to 2022–23

The interactive visualisation shows the number of family and domestic violence Crisis Payment claims granted per year by gender and sub-category of Crisis Payment. Between 2015–16 and 2022–23 the most common sub-category of family and domestic violence Crisis Payment each year was Victim left home, regardless of gender.

Redress payments

For people who have experienced institutional child abuse, payments are also available through the National Redress Scheme. The National Redress Scheme is designed to acknowledge that many children were sexually abused in Australian institutions; recognise the suffering they endured because of this abuse; hold institutions accountable for this abuse; and help people who have experienced institutional child sexual abuse gain access to counselling, a direct personal response, and a redress payment (Box 2).

The National Redress Scheme was created in response to the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. A person can apply under the scheme if they experienced institutional child sexual abuse before 1 July 2018, are aged over 18 or will turn 18 before 30 June 2028 and are an Australian citizen or permanent resident.

Under the scheme, an offer of redress consists of 3 components:

- counselling and psychological care

- a redress payment

- a direct personal response from participating institution/s responsible for the abuse.

People can apply for redress at any time until 1 July 2027.

For more information about the scheme, see National Redress Scheme.

In 2021–22:

- 6,000 people applied to the Scheme for redress

- 3,100 determinations were made and of these, 3,000 people were determined as eligible for redress, 90 applications were deemed ineligible.

- 2,700 people accepted an offer of redress

- 36 people declined an offer of redress (DSS 2022a).

More than 1,300 institutions were found to have been responsible for abuse, and almost 2,700 redress payments were made ranging from less than $10,000 to $150,000, with an average payment of around $90,800. The total value of redress monetary payments was $242.9 million, and just over 2,200 people accepted the offer of counselling and psychological care services as part of their redress outcome (DSS 2022a).

Since 1 July 2018, 17,100 people have applied to the scheme and 8,700 have accepted an offer of redress (Figure 3) (DSS 2019; DSS 2020; DSS 2021; DSS 2022).

Figure 3: National redress scheme, applications and accepted offers, 2018–19 to 2021–22

| Year | Applied for redress | Accepted offer of redress |

|---|---|---|

| 2018–19 | 4,200 | 239 |

| 2019–20 | 3,127 | 2,568 |

| 2020–21 | 3,773 | 3,225 |

| 2021–22 | 5,987 | 2,713 |

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

Australian Government Department of Social Services National Redress Scheme data

|

Data source overview

A person who accepts an offer of redress in a given time period, may have applied to the redress scheme in previous years of operation. There are a number of reasons why applications for redress are not finalised, for example, where relevant institutions have not joined the scheme, or where more information is being sought from an applicant. Since 2018–19, the number of institutions participating in the scheme has increased.

Income support receipt among specialist homelessness services clients experiencing FDV

The Specialist homelessness services clients experiencing family and domestic violence: interactions with out-of-home care and income support report includes comparison data on income support (IS) receipt between specialist homelessness services clients who had experienced FDV (FDV cohort) and those who did not (non-FDV cohort) between 2011–2021. It found that among the FDV cohort that received IS:

- Four in 10 (39%) received IS for 7–10 years, compared with 3 in 10 (31%) of the non-FDV cohort who received IS.

- Two in 5 (43%) had ever received the Parenting Payment Single, compared with 1 in 5 (21%) of the non-FDV cohort who received IS.

- A higher proportion (15%) received the Parenting Payment Single as their first payment type, compared with the non-FDV cohort (6.6%). As most of the FDV cohort were female (80%), this suggests these clients were likely to be single mothers with young children (AIHW 2024).

Financial and banking services

People who experience FDV may also receive support from banks and financial institutions. Banks can play a role in identifying FDV, particularly when financial or economic abuse has occurred in the context of intimate partner violence or coercive control. Data from banks are currently limited. For more information on economic abuse, see intimate partner violence.

Workplace responses for employees

Workplaces can respond to violence FDV in many ways, for example, by making resources and supports available for people to access if it occurs. Workplaces can also respond to specific instances of sexual violence, and take formal actions to provide support to victim-survivors or hold perpetrators to account.

Leave entitlements

People who experience FDV may need to take time off work to make arrangements for their safety, access police and specialist services, or attend appointments with medical, financial, legal or health professionals.

One way workplaces can support individuals is by granting time off work. Under the National Employment Standards (NES), all employees in Australia are entitled to unpaid FDV leave. In October 2022, these entitlements were replaced with an entitlement to paid FDV leave (Box 3).

In Australia, all employees (including part-time and casual employees) are entitled to 5 days unpaid leave in a 12-month period if they have experienced FDV. FDV means violent, threatening or other abusive behaviour by an employee’s close relative that seeks to coerce or control the employee, and/or causes them harm or fear.

A close relative is:

- an employee's spouse or former spouse, de facto partner or former de facto partner, child, parent, grandparent, grandchild, sibling

- an employee's current or former spouse or de facto partner's child, parent, grandparent, grandchild or sibling, or

- a person related to the employee according to Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander kinship rules.

More information about FDV leave is available on the Fair Work Ombudsman website, at Family & domestic violence leave.

Entitlement to paid FDV leave

In October 2022, the Fair Work Amendment (Paid Family and Domestic Violence Leave) Bill was passed. The Bill amended the Fair Work Act 2009 and replaced the current entitlement in the NES (to 5 days of unpaid FDV leave in a 12-month period) with an entitlement to 10 days of paid FDV leave for full-time, part-time and casual employees. The Bill also: extends the definition of FDV to include conduct of a current or former intimate partner of an employee, or a member of an employee's household.

The leave will be available from:

- 1 February 2023, for employees of non-small business employers (employers with 15 or more employees on 1 February 2023)

- 1 August 2023, for employees of small business employers (employers with less than 15 employees on 1 February 2023).

More information about the new paid FDV leave entitlements can be found on the Fair Work Ombudsman website at New paid family and domestic violence leave.

While the NES sets out the minimum entitlements for all employees covered by the national workplace relations system, some people are covered by registered agreements, enterprise awards or state reference public sector awards, and have access to further entitlements.

Data from the Workplace Agreements Database are available to report on the number of agreements approved that contain an entitlement to paid FDV leave, and the number of people covered by these agreements. Note that these data are only available from 2016 and cannot be used to show the uptake of leave entitlements.

In 2021, there were 1,900 agreements approved which included paid FDV leave entitlements. These agreements covered 354,000 employees, and made up 44% of new approved agreements that year. The proportion of approved agreements with paid FDV leave entitlements has generally risen over time – from 21% in 2016 to 44% in 2021. (Attorney-General’s Department unpublished).

Employees will continue to be entitled to 5 days of unpaid family and domestic violence leave until they can access the new paid entitlement.

How can workplaces best support people who are experiencing FDV?

'Workplaces could provide confidential supervision, or better promotion of employee assistance programs, more information on vicarious trauma in the workplace, and a discrete way to apply for FV leave. While I know it’s available, many co-workers don’t apply for fear of judgement and repercussions.'

Kelly

Keeping workplaces safe

Another way that workplaces respond to FDSV, is through implementing initiatives or adopting strategies to make the workplace a safe space for employees, or having policies in place to provide support when FDV or SV occurs.

Data from the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA) show that in 2021–22, 98% of the almost 4,800 organisations surveyed had policies and strategies in place targeting sexual harassment. Many of the organisations (73% or almost 3,500) surveyed also had formal policies or strategies in place to support employees experiencing family and domestic violence. This has doubled over the last 8 years (WGEA 2022).

These data highlight that responding to sexual violence in the workplace remains a key priority (Box 4).

The National Inquiry into Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces was announced in June 2018. It was conducted by the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) and builds on the data collected in the National Survey on Sexual Harassment in Australian workplaces. The purpose of the Respect@Work inquiry was to improve how Australian workplaces prevent and respond to sexual harassment. The AHRC received 460 submissions from government agencies, business groups, community bodies and victims. From September 2018 to February 2019, it conducted 60 consultations. These consultations informed the inquiry report, which outlines:

- the current context in which workplace sexual harassment occurs

- what is understood about workplace sexual harassment

- how primary prevention initiatives outside the workplace can be used to address workplace sexual harassment

- the current legal and regulatory systems for responding to workplace sexual harassment and how these can be improved

- a proposed new framework for workplaces to address sexual harassment

- the support, advice and advocacy services that are available, and how access to these services, can be improved (AHRC 2020).

The inquiry made 55 recommendations across a range of areas. The Australian Government’s response to these is outlined in the Roadmap to Respect report. Five reform priorities were identified:

1. establishing the Respect@Work Council

2. conducting data collection and research on workplace sexual harassment

3. initiating targeted education and training initiatives and the development of resources

4. adopting a joined-up approach across agencies, support services, legal assistance providers and other bodies to ensure better advice and support on workplace sexual harassment issues

5. supporting disclosure of historical workplace sexual harassment (AHRC 2020).

For more information, see Respect@Work: Sexual Harassment National Inquiry Report.

Data on workplace sexual harassment, are reported in sexual violence.

In recent years, several initiatives have included introducing law reforms or developing resources as a response to sexual violence that occurs in workplaces and in institutions:

- The Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) developed the National Principles for Child Safe Organisations which were endorsed by the Council of Australian Governments on 19 Feb 2019. A suite of 11 Child Safe Organisation e-learning modules were also designed to help organisations increase their knowledge and understanding of the National Principles and identify the steps they need to take as they work towards implementing them.

- Safe Work Australia has published a Model Code of Practice: Sexual and gender-based harassment and the guide Preventing workplace violence and aggression. These documents provide practical guidance to minimise the risk of sexual and gender-based harassment and gendered violence in the workplace.

- In 2021, The Sex Discrimination and Fair Work (Respect at Work) Amendment Act 2021 (Respect at Work Amendment Act) took effect. This Act aims to make sure more workers are protected and empowered to address unlawful sexual harassment in the workplace by amending the Fair Work Act 2009 and Sex Discrimination Act 1984.

Responses from specific organisations

Some workplace responses to FDSV are specific to the forms of violence, employers or industries. Experiences of sexual violence in universities, and some of the actions taken, are discussed in sexual violence. In some instances, workplace responses address violence that has occurred within the workplace, or in a work-related environment.

Sexual assault in the Australian Defence Force

Data are available from the Australian Defence Force on the reported number of sexual assault incidents per year. These assaults include matters of a historical nature, such as those that occurred more than one year before reporting. Reporting sexual misconduct triggers a further inquiry or investigation by the Joint Military Police Unit (JMPU) or state/territory police.

In 2021–22, there were 148 incidents of sexual assault reported. Of these:

- 88 were aggravated sexual assaults (penetrative acts committed without consent, threat of penetrative acts committed with aggravating circumstances, or instances where consent is unable to be given)

- 60 were non-aggravated sexual assaults (for example, touching of a sexual nature without consent where penetration does not occur) (Department of Defence 2022).

About 48% of allegations of sexual assault made to the JMPU were made by members who did not wish to make a statement of complaint, did not want the matter investigated by the JMPU or state/territory police or withdrew their complaint. The number of reported sexual assault incidents was lower in 2021–22 than in previous years – 187 in 2020–21, 160 in 2019–20, 166 in 2018–19 and 170 in 2017–18. Due to differences in reporting frameworks, these numbers cannot be compared with those before 2017–18 (Department of Defence 2022).

Support for Defence personnel regarding matters of sexual violence is also provided through the Department of Defence’s Sexual Misconduct Prevention and Response Office (SeMPRO) (Box 5).

The overarching intent of SeMPRO is to help people who impacted by sexual misconduct and prevent sexual misconduct in Defence workplaces. SeMPRO works to do this by:

- providing education and training about sexual misconduct to Defence personnel

- providing client support to people affected by sexual misconduct

- shaping Defence policy to provide accessible resources that aid those impacted by sexual misconduct, their supporters, and managers.

SeMPRO also offers support to those around people directly affected by sexual misconduct – such as commanders, managers, colleagues, friends, and family members – to help them provide support to a friend or colleague, or manage an incident.

For more information, see Sexual Misconduct Prevention and Response Office.

In 2021–22, SeMPRO assisted 440 clients. Of these clients, 213 were directly affected by sexual misconduct (sexual offences, sexual harassment, sex-based discrimination, or adjacent incidents such as stalking and intimate image abuse. SeMPRO clients were majority women (88%).

For the third consecutive year, the 1800 SeMPRO Service saw an increase in client demand from those directly impacted by sexual misconduct. (Department of Defence 2022).

The Office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman, within its Defence Force Ombudsman jurisdiction, receives reports of contemporary and historic serious abuse within the Australian Defence Force.

The Defence Force Ombudsman provides a confidential mechanism to report serious abuse for those who feel unable, for whatever reason, to access Defence’s internal mechanisms.

Serious abuse means sexual abuse, serious physical abuse or serious bullying or harassment that occurred between 2 (or more) people who were members of Defence at the time. Reports received by the Ombudsman are assessed against several thresholds to determine if they can be accepted as a report of serious abuse in Defence.

Between December 2016 to December 2022:

- almost 4,100 reports of abuse were received, of which nearly 210 reports were withdrawn, leaving almost 3,900 reports

- almost 2,700 assessment decisions were made with nearly 2,400 reports considered wholly or partially within the jurisdiction of the Defence Ombudsman. Of the reports that contained incident data, more than 1,200 involved sexual abuse (Office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman 2022).

Related material

More information

AHURI (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute) (2021) Housing, homelessness and domestic and family violence, AHURI, accessed 11 July 2022.

AHRC (Australian Human Rights Commission) (2020) Respect@Work: Sexual Harassment National Inquiry Report, AHRC, Australian Government.

Attorney-General’s Department (unpublished), Workplace Agreements Database data, AGD, Australian Government.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2024) Specialist homelessness services clients experiencing family and domestic violence: interactions with out-of-home care and income support, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 July 2024.

Department of Defence (2022) Annual report 2021–22, Department of Defence, Australian Government

DSS (Department of Social Services) (2019) Annual report 2018–19, DSS, Australian Government.

DSS (2020) Annual report 2019–20, DSS, Australian Government.

DSS (2021) Annual report 2020–21, DSS, Australian Government.

DSS (2022a) Annual report 2021–22, DSS, Australian Government.

DSS (2022b) National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022–2032, DSS, Australian Government.

HRSCSPLA (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs) (2021) Inquiry into family, domestic and sexual violence, Parliament of Australia, Australian Government, accessed 22 July 2022.

Office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman (2022) Reporting abuse in Defence statistics, Commonwealth Ombudsman, Australian Government.

Services Australia (2023) Crisis Payment for extreme circumstances family and domestic violence - Services Australia, Services Australia website, accessed 28 July 2023.

WGEA (Workplace Gender Equality Agency) (2022) WGEA Data Explorer, WGEA website, accessed 2 August 2023.

- Previous page Legal systems

- Next page Specialist perpetrator interventions