LGBTIQA+ people

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

Key findings

Of respondents to the 2019 Private Lives 3 survey:

The term LGBTIQA+ is used to refer to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer, asexual people, or people otherwise diverse in gender, sexual orientation and/or innate variations of sex characteristics. Alternative abbreviations may be used in data sources when discussing specific groups within LGBTIQA+ populations.

Research indicates that most LGBTIQA+ people experience some form of violence in intimate partner and/or family relationships in their lifetime. The impacts of these experiences are profound, far-reaching and compounded by stigma, prejudice and discrimination towards LGBTIQA+ people. The drivers of violence are often the same as those identified for violence against women (AHRC 2015; Campo and Tayton 2015; DSS 2022; Hill et. al 2020).

LGBTIQA+ people are recognised as population groups that experience health and wellbeing disparities due to stigma and discrimination. The National Plan to End Violence against Women and their Children 2022–2032 (the National Plan) recommends increased attention to LGBTIQA+ communities to address the high prevalence of violence against LGBTIQA+ people (Campo and Tayton 2015; DSS 2022; Hill et al. 2020).

LGBTIQA+ language

People may use a wide range of terms to describe gender, sexual orientation and innate variations of sex characteristics, and some people may not identify with or use certain terms (Box 1). The terms and language used by LGBTIQA+ people to define their identity are influenced by many factors, including their age, ethnicity, socioeconomic position, and their lived experiences and relationships with others (AIHW 2018).

While reporting on LGBTIQA+ people together provides useful high-level insights, it conceals diversity within the group. It is important to note that there are many factors that can combine to create a risk and experience of violence that is unique to each person, and an individual included in the term LGBTIQA+ may not identify as being part of any single group.

Asexual: A sexual orientation that reflects little to no sexual attraction. People who identify as asexual can still experience romantic attraction.

Bisexual/bi: A sexual orientation that reflects sexual and/or romantic attraction towards 2 or more genders. Bisexuality is not exclusive to binary genders.

Brotherboy/brothaboy: A term used by some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) communities to describe gender diverse First Nations people who have a male spirit and take on male roles within the community.

Cisgender: The cisgender (cis) experience of gender is defined for persons whose gender is the same as what was presumed for them at birth.

Gay: A sexual orientation that describes sexual and/or romantic attraction to people of the same gender. This term is most commonly applied to men, although some women use this term.

Gender/gender identity: Gender is a social and cultural concept. It is about social and cultural identity, expression and experience as a man, woman or non-binary person. Gender identity is about who a person feels themself to be. Gender expression is the way a person expresses their gender; person's gender expression may also vary depending on the context, for instance expressing different genders at work and home. Gender experience describes a person’s alignment with the gender presumed for them at birth, i.e. a cis experience or a trans experience.

Heterosexual: A sexual orientation towards people of a different gender.

Intersex: Intersex refers to people with innate genetic, hormonal or physical sex characteristics that do not conform to medical norms for female or male bodies. This is also called 'variations of sex characteristics'. Intersex does not refer to a particular gender identity or sexual orientation; intersex people old enough to freely express an identity may be heterosexual or not, and cisgender or not.

Lesbian: A sexual orientation most often used by women whose primary sexual and/or romantic attraction is to other women.

Non-binary: Non-binary is an umbrella term describing gender identities that are not exclusively male or female.

Pansexual: A sexual orientation not restricted by gender. Pansexuality can include sexual and/or romantic attraction towards any person, regardless of their gender.

Queer: A term used to describe a range of sexual orientations and gender identities. For some it is a reclaimed derogatory term and represents a political movement that celebrates difference, although it is still sometimes used against non-heterosexual and non-cisgender people in a derogatory manner and considered derogatory by many older LGBTIQA+ people.

Sex: A person's sex is based upon their sex characteristics, such as their chromosomes, hormones and reproductive organs. While typically based upon the sex characteristics observed and recorded at birth or infancy, a person's sex can change over the course of their lifetime and may differ from their sex recorded at birth.

Sexual orientation: An umbrella concept that encapsulates: sexual identity (how a person thinks of their sexuality and the terms they identify with), attraction (romantic or sexual interest in another person), and behaviour (sexual behaviour). It is a subjective view of oneself and can change over the course of their lifetime and in different contexts.

Sistergirl/sistagirl: A term used by some First Nations communities to describe gender diverse First Nations people who have a female spirit and take on female roles within the community.

Trans and gender diverse (trans): The trans and gender diverse (trans) experience of gender is defined for persons whose gender is different to what was presumed for them at birth.

Variations of sex characteristics: See ‘Intersex’.

Sources: ABS 2021; AIFS 2022; DSS 2022; IHRA 2021.

What do we know?

Measuring violence experienced by LGBTIQA+ people

National reporting on the health and wellbeing of LGBTIQA+ people is often limited by a lack of data on gender, sexual orientation and innate variations of sex characteristics in data collections. Where data are available, it most often refers to people who identify as gay, bisexual, or heterosexual. Certain groups such as trans, asexual and intersex people remain under-researched and -reported; and current data do not fully describe the complexities and diversities among LGBTIQA+ people (AIHW 2018; Campo and Tayton 2015; DSS 2022).

The Standard for Sex, Gender, Variations of Sex Characteristics and Sexual Orientation Variables, 2020 was developed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) to standardise the collection and dissemination of data relating to sex, gender, variations of sex characteristics and sexual orientation. Work to implement the standard in national surveys has commenced and will improve the availability of data on LGBTIQA+ people (ABS 2021). In particular, the 2021–22 ABS Personal Safety Survey (PSS) collected data on sexual orientation for the first time to support understanding of the prevalence of FDSV among people with different sexual identities (ABS 2023b, see Box 3). Implementation of the standard is also being considered in national administrative data collections. For example, there was national agreement to collect and supply data on the gender of people admitted to Australian hospitals from 2022–23 (see Admitted Patient Care National Minimum Data Set).

The terms and abbreviations used to describe LGBTIQA+ people can vary depending on the groups or topics being discussed, and the ways in which data are collected. Unless otherwise stated, the AIHW’s FDSV reporting uses the terms and abbreviations used by the data source – for example, where data sources have data only for LGBT people, this terminology has been used within this topic page.

Similarly, the terms used to describe a person’s sex or gender will depend on how this information is collected in a particular data source. This means that binary language is often used in the AIHW’s FDSV reporting to describe data. The AIHW recognises that binary language does not represent the experiences of all people, and that some people, particularly gender diverse people, may not identify with these terms. Specific information about how sex and/or gender are collected in each data source, is included in the Data sources and technical notes, where available.

What distinct forms of violence are experienced by LGBTIQA+ people?

Discrimination against LGBTIQA+ people may increase their risk of experiencing distinct forms of family, domestic and/or sexual violence (FDSV) when compared with other population groups. However, some LGBTIQA+ people can experience distinct forms of violence that may be referred to as identity-based abuse. Identity-based abuse may include behaviours such as:

- pressuring a person to conform to gender norms or stop them from accessing gender affirming care

- corrective rape (a hate crime in which the victim is raped because of their perceived sexual orientation)

- threatening to ‘out’ the person’s gender, sexuality, HIV status or intersex status

- exiling a person from family due to their sexuality or gender

- forcing a family member into conversion therapy (DSS 2022).

Intersex people may also experience body shaming, along with forced and coercive medical interventions and body modifications in childhood and adulthood, as a result of stigma and misconceptions about intersex variations (DSS 2022).

Additionally, a lack of understanding of these issues by support services may present unique barriers to accessing support for LGBTIQA+ people (Cullen et al. 2022; DSS 2022).

Barriers to accessing help

LGBTIQA+ people may experience many barriers to accessing help that are shared with the general population including, but not limited to, the fear of not being believed, shame related to being a ‘victim’ and not recognising behaviours (in particular non-physical forms) as violence or abuse (Backhouse & Toivonen; DSS 2022; Lusby et al. 2022).

Barriers that are specific to LGBTIQA+ people or may have a larger effect among them include:

- experiences and/or fear of discrimination

- the use of frameworks based on heteronormativity and cisgenderism to determine who perpetrates and experiences violence – for example, determining the primary aggressor based on presumed assigned sex at birth, perceived masculinity and/or assumed strength.

- the historical framing of FDSV as ‘violence against women’ (for example, if funding contracts stipulate that funding is to address violence against women) may limit the ability of services to support people who are not cisgender women (including trans women; gay, bisexual or trans men; non-binary people)

- a lack of data to indicate the need for services (Hegarty et al. 2022; Lusby et al. 2022).

What do the data tell us?

The main data source used in this topic page is the La Trobe University Private Lives 3 survey (see Box 2).

La Trobe University’s research series, Private Lives, is currently the largest national survey focused on the health and wellbeing of LGBTIQ people. In 2019, Private Lives 3 collected FDSV data from 6,835 LGBTIQ respondents aged 18 to 80+ years from a wide range of gender identities and sexual orientations. As the survey uses a non-probability convenience sample, the results may not be representative of the Australian LGBTIQA+ population and cannot be generalised to this population group. Comparative data was not available for all groups due to data limitations (Hill et al. 2020).

Whilst this survey included participants with an intersex variation/s, the data are not able to be disaggregated by this category and, therefore, the acronym LGBTQ+ is used when referring to the Private Lives 3 results. For more information see Data sources and technical notes.

The survey included questions about family violence and intimate partner violence. Family violence was described as abuse by a family member(s), including both birth and chosen family. Intimate partner violence was described as abuse by a partner(s) in an intimate relationship, noting that intimate relationships may be either sexual or not sexual in nature (Hill et al. 2020).

Respondents were provided with a list of specific violent behaviours and asked to indicate whether they had ever experienced them from intimate partners or family members. This included: physical violence, sexual assault, verbal abuse, emotional abuse, financial abuse, harassment or stalking, damage to property, social isolation, threats of suicide and self-harm, LGBTIQ-related abuse, and other. ‘LGBTIQ-related abuse’ included: shamed you about being LGBTIQ, threatened to ‘out’ you or your HIV status, or withheld hormones or medication (Hill et al. 2020).

Compared to when asked more generally if they had ever experienced violence, when these specific forms of violence were explicitly listed, the proportion of people who reported having ever experienced violence increased from 42% to 61% for intimate partner violence, and from 39% to 65% for family violence (Hill et al. 2020). FDSV is often a highly personalised experience and may not be recognised or reported as abuse by the individual.

Intimate partner violence and family violence

In 2019, 3 in 5 (61%) respondents to the Private Lives 3 survey had ever experienced intimate partner violence. Emotional abuse (48%), verbal abuse (42%), and social isolation (27%) were the most commonly reported types of intimate partner violence experienced (Figure 1). Cisgender men (57%) were the most common perpetrator, followed by cisgender women (35%) (Hill et al. 2020).

Figure 1: Types of intimate partner and family violence ever experienced by LGBTQ+ people, by perpetrator type, 2019

| Violence type | Intimate partner | Family member |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | 25.0% | 24.2% |

| Verbal | 42.4% | 41.5% |

| Sexual | 21.8% | 9.7% |

| Financial | 16.1% | 9.2% |

| Emotional | 48.1% | 39.3% |

| Harassment or stalking | 16.5% | 6.6% |

| Property damage | 9.6% | 8.0% |

| Social isolation | 26.7% | 18.3% |

| Threats of self-harm or suicide | 23.1% | 7.9% |

| LGBTIQ-related abuse | 10.0% | 40.8% |

| Other | 1.4% | 1.6% |

| None of these | 39.3% | 35.1% |

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

La Trobe University Private Lives 3 survey

|

Data source overview

Similarly, 2 in 3 (65%) respondents had ever experienced family violence, not including intimate partner violence. Verbal abuse (42%), LGBTIQ-related abuse (41%), and emotional abuse (39%) were the most common types of violence experienced from a family member (Figure 1). Almost 3 in 4 (73%) indicated the perpetrator of family violence was a parent (including guardian, foster carer, step-parent, or adoptive parent (Hill et al. 2020).

Respondents overall were more likely to experience violence from intimate partners than family members for all forms of violence, except LGBTIQ-related abuse, where 41% indicated abuse occurred from a family member, compared with 10% from an intimate partner (Hill et al. 2020).

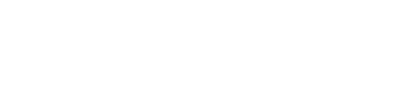

There was some variation in experiences of violence by gender:

- Non-binary respondents consistently indicated higher proportions of violence by any perpetrator when compared to other gender identities. This was consistent across all types of violence except for verbal violence perpetrated by a family member, which was highest for transgender men.

- Transgender men had the second highest proportion of violence by type of violence and perpetrator, followed by cisgender women, trans women and cisgender men.

- Cisgender men reported the lowest rates of violence across all types of violence by any perpetrator (Figure 2).

Overall, experiences of violence by sexual orientation varied depending on the type of violence:

- Verbal violence was the most common type of violence experienced for all sexual orientations, regardless of perpetrator type.

- All types of violence, regardless of perpetrator, were most commonly experienced by pansexual and queer respondents (Figure 2).

Broadly speaking, respondents who identified as lesbian or gay were more likely to experience physical or verbal violence from an intimate partner than from a family member. Conversely, respondents who identified as bisexual, pansexual, queer, asexual or something else experienced physical and verbal violence at higher levels from family members than intimate partners (Hill et al. 2020).

Figure 2: Types of intimate partner and family violence ever experienced, by gender, sexual orientation and perpetrator type, 2019

Bar graph that shows the proportion of survey respondents who had ever experienced physical, verbal or sexual violence, by whether the perpetrator was an intimate partner or family member, and by the respondent's gender and sexual orientation.

Sexual assault

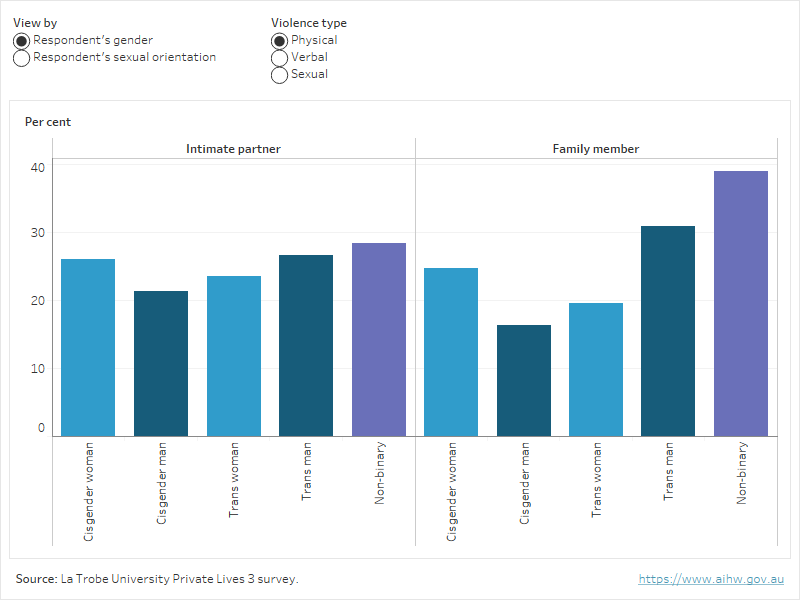

Almost half of all respondents (49%) to the Private Lives 3 survey indicated having ever experienced sexual assault and 8.9% had experienced sexual assault in the past 12 months (Hill et al. 2020).

Figure 3: Experience of sexual assault, by gender and sexual orientation, 2019

Figure 3 is a bar graph that shows the proportion of survey respondents who had experienced sexual assault in the last 12 months, or experienced sexual assault ever, by the respondent's gender and sexual orientation.

The majority of queer, pansexual and bisexual identifying respondents had experienced sexual assault in their lifetime. Additionally, a large proportion of lesbian (46%), asexual (45%) and gay (34%) respondents had experienced sexual assault at some point in their life (Figure 3).

The majority of non-binary, cisgender women and trans men had experienced sexual assault in their lifetime. Additionally, many trans women (42%) and cisgender men (35%) had experienced sexual assault at some point in their lifetime (Figure 3).

For the most recent sexual assault, the perpetrator was most commonly identified as a former intimate partner (22%), current intimate partner (19%), friend (19%), casual encounter (19%) or stranger (18%).

The most common gender of perpetrator of the most recent incident of sexual assault were cisgender men (84%). Perpetrators were also identified as cisgender women (14%), non-binary people (1.8%), trans women (1.3%) and trans men (1.2%).

For the first time, the 2021–22 PSS collected data on sexual orientation. Some 2021–22 data were available on women aged 18 years and older who had experienced sexual violence (which includes sexual assault and sexual threat), and cohabiting partner violence and emotional abuse (which includes any violence from someone the person lives with or lived with in a married or de facto relationship). Data for other groups of people were not sufficiently statistically reliable for reporting (ABS 2023a, 2023c).

The 2021–22 PSS estimated that:

- LGB+ women were over 5 times more likely than heterosexual women to have experienced sexual violence in the past 2 years (13% compared with 2.4%)

- for the vast majority of LGB+ and heterosexual women who had experienced sexual violence in the last 2 years (98% for both groups), the perpetrator was male (ABS 2023c).

There were no statistically significant differences between LGB+ and heterosexual women in the experience of violence or emotional abuse by a cohabiting partner in the last 2 years:

- violence by a cohabiting partner in the last 2 years was experienced by 3.9%* of LGB+ women and 1.6% of heterosexual women (* indicates the estimate has a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution)

- emotional abuse by a cohabiting partner in the last 2 years was experienced by 7.1% of LGB+ women and 5.2% of heterosexual women (ABS 2023a).

Child maltreatment

In the 2021 Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS, see Box 4), just under 1 in 10 (9.5%) participants identified with a diverse sexuality (those who responded in any way other than heterosexual or straight) and 0.9% with a diverse gender (those who responded in any way other than man or woman). Weighted estimates were reported for the experience of child maltreatment for diverse gender and sexuality identities.

Participants who have experienced child maltreatment are those who reported they experienced any of the five types of maltreatment (physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, exposure to domestic violence) as a child (before the age of 18). For more information about this study, see Children and young people: Measuring the extent of violence against children and young people and Data sources and technical notes.

The Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS) was a cross-sectional survey of just over 8,500 participants aged 16 years or more between 9 April and 11 October 2021. People were considered to be eligible for participation if they were aged 16 years or more, in an age group for which participants were required when contacted and had sufficient English language proficiency for participation. The final response rate was 4.0% when based on the estimated number of eligible participants (about 210,000 people) and 14% when based on eligible participants contacted (about 60,800 people) (Haslam et al. 2023).

Sexuality identity

To determine sexuality identity, participants were asked “How would you describe your sexuality?” with the response codes: heterosexual or straight; gay or lesbian; bisexual; queer; asexual; pansexual; ‘I prefer not to have a label’; and other (Higgins et al. 2024).

Gender identity

To determine gender identity, an open-response question “How would you describe your gender?” was asked and coded from a set of response codes including male/cisgender man, female/cisgender woman, trans woman, trans man, trans femme, transmasculine, gender queer, gender diverse, non-binary, sister girl, brother boy, agender, or “I prefer not to have a label”.

The categories ‘men’ and ‘women’ include anyone who identified as men and women respectively, regardless of sex assigned at birth, and as such, may include some people who are not cisgender men and women.

Participants who responded that they were ‘cisgender’ were asked to confirm if they were a man or woman.

Participants who responded that they were ‘male’ were recorded as a man; those who responded that they were ‘female’ were recorded as a woman (Higgins et al. 2024).

Figures presented from the ACMS have been rounded. For exact figures, please see the cited primary source.

The ACMS found that:

- The proportion of sexuality diverse participants who had experienced any type of child maltreatment (84%) was significantly higher than for heterosexual participants (61%). This pattern was observed for all types of maltreatment.

- Sexuality diverse participants were significantly more likely to experience more than one type of child maltreatment (multi-type maltreatment) than heterosexual participants:

- Almost 2 in 3 (64%) sexuality diverse participants had experienced 2 or more types of maltreatment compared with 38% of heterosexual participants

- Just under half (47%) of sexuality diverse participants had experienced 3 or more types of maltreatment compared with 22% of heterosexual participants (Higgins et al. 2024).

Similar findings were also reported for gender diverse participants:

- The proportion of gender diverse participants who had experienced any type of child maltreatment (82%) was significantly higher than for women (66%) and men (58%). This pattern was observed for all types of maltreatment.

- Gender diverse participants were significantly more likely to experience more than one type of child maltreatment (multi-type maltreatment) than women and men:

- 2 in 3 (66%) gender diverse participants had experienced 2 or more types of maltreatment compared with 43% of women and 35% of men

- 1 in 2 (51%) gender diverse participants had experienced 3 or more types of maltreatment compared with 28% of women and 18% of men.

- A higher proportion of gender diverse participants aged 16–24 years (91%) had experienced child maltreatment when compared with older gender diverse participants (82% for those aged 25-44 years and 70% for those aged 45 years or more) (Higgins et al. 2024).

Technology-facilitated violence

The Office of the eSafety Commissioner surveyed more than 3,700 Australian adults aged 18 to 65 on general online safety. The report from eSafety identified LGBTQI+ people as an at risk group for serious online abuse. One in 3 (36%) lesbian, gay and bisexual people reported experiences of image-based abuse compared with 1 in 5 (21%) heterosexual people in Australia. The survey concluded that cyber abuse, image-based abuse and homophobic or transphobic abuse disproportionately affected young LGBTQI+ people (eSafety 2020).

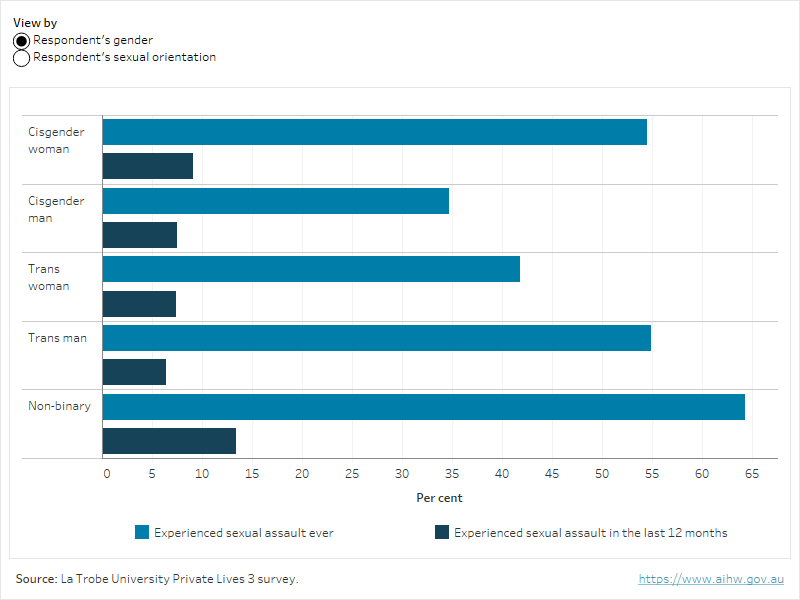

Additionally, a series of research papers from the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) examined dating app-facilitated sexual violence (DAFSV), and the disproportionate impact this has on non-heterosexual people. DAFSV is described as sexual harassment, aggression and other violence that occurs online, or facilitates in-person violence. In 2021, almost 10,000 people aged 18 and older who had used a mobile dating app or website in the last five years were surveyed, of which 1,613 identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, pansexual or not heterosexual (LGB+) (Lawler and Boxall 2023; Teunissen et al. 2022; Wolbers et al. 2022). Among all respondents, almost 3 in 4 (73%) had experienced at least one form of online and/or in-person DAFSV within the last 5 years, and around half (45%) said they had experienced both. The occurrence of violence was especially high for LGB+ women and men, followed by non-binary people and heterosexual women, when compared with heterosexual men. LGB+ respondents were more likely to experience violence online than in-person, and sexual harassment was the most commonly reported type of online violence (Figure 4) (Wolbers et al. 2022). See also Stalking and surveillance.

Figure 4: Experience of online and in-person dating app-facilitated sexual violence (DAFSV) in the last 5 years, by gender and sexual orientation, 2021

Figure 4 is a bar graph that shows the proportion of survey respondents who had experienced online and in-person dating app-facilitated sexual violence, by the type of violence, and by the respondent's gender and sexual orientation.

The survey also found:

- Despite disproportionate levels of DAFSV, LGB+ women and men had much lower rates of reporting their most recent experience to police when compared with heterosexual men.

- When DAFSV was reported to police, LGB+ men and women were more likely to report negative experiences than their heterosexual counterparts. See also FDV reported to police and Sexual assault reported to the police.

- Across all groups, LGB+ men were most likely to report they had received requests for child sexual exploitation materials while using dating apps/websites. Inappropriate requests may include asking for photos of children, questions about children of a sexual nature or offering payment for image-based content of children. This does not mean that these respondents perpetrated child sexual exploitation. The gender of the person requesting content cannot be determined from the data provided (Lawler and Boxall 2023; Teunissen et al. 2022; Wolbers et al. 2022).

Lesbian and bisexual women

There are often complex ways in which the drivers of violence against women and the drivers of violence against LGBTIQA+ people intersect; particularly regarding the binary and rigid constructions of gender (DSS 2022). Previous studies of FDSV in the general population have largely focused on heterosexual women and pose challenges for making valid comparisons with LGBTIQA+ communities.

A comparative analysis of almost 9,000 women from the 2003 Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH, see Data sources and technical notes) provides some insight into experiences of violence for lesbian, bisexual and mainly heterosexual women compared with exclusively heterosexual women. The data do not indicate the gender of perpetrators of violence (AIHW 2019; Szalacha et al. 2017).

One in 4 (25%) women who identified as bisexual or mainly heterosexual, and roughly 1 in 6 (15%) women who identified as lesbian, reported that they had ever been in a violent relationship, compared with 1 in 10 (10%) women who identified as exclusively heterosexual (AIHW 2019; Szalacha et al. 2017).

Bisexual women reported higher proportions across all types of violence (emotional, physical, sexual abuse and sexual harassment) and were more likely to experience stress, anxiety, depression and poor mental health, when compared with women who identified as lesbian, mostly heterosexual, or exclusively heterosexual (AIHW 2019; Szalacha et al. 2017).

Regardless of sexual orientation, emotional abuse was the most commonly reported type of violence. When compared with exclusively heterosexual women, women who identified as bisexual, lesbian or mostly heterosexual were:

- 2 to 3 times as likely to have been in a violent relationship in the past 3 years

- twice as likely to report physical abuse by a partner (AIHW 2019; Szalacha et al. 2017).

Gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer men

In 2017–18, University of Western Sydney and ACON, surveyed almost 900 gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer men on sexual and gender identity; experiences of intimate partner violence; attitudes to violence; and bystander awareness and willingness to intervene.

Of the men surveyed in 2017-18, 3 in 5 (62%, or 556) reported that they had experienced physical, verbal or emotional abuse in a relationship, and almost 1 in 4 (26%, or 138) had experienced abuse within the last year (Ovenden et al. 2019).

Respondents most commonly reported that they had discussed their abusive relationship with:

- a friend or neighbour (35%)

- counsellor or psychologist (18%)

- family or relative (17%).

However, 1 in 6 (17%) did not discuss their experience of abuse with anyone (Ovenden et al. 2019).

Around 2 in 5 (43%) respondents reported witnessing violence or abuse between men in a relationship, of which, over three quarters intervened in some way. The form of intervention was most commonly verbal (41%), followed by physical (14%), and sought help (13%). About 1 in 4 (23%) did not know what to do while 1 in 8 (13%) did not intervene (Ovenden et al. 2019).

Services and support seeking-behaviour among LGBTIQA+ people

FDSV specialist services

The 2020 Australian Government House of Representatives inquiry into FDSV identified a variety of barriers to LGBTIQA+ people reporting FDSV and seeking help, including homophobia, transphobia and a fear of discrimination (HRSCSPLA 2021).

LGBTIQA+ people are far less likely than the general population to find support services that meet their distinct needs (DSS 2022). Additionally, a national survey by the University of New South Wales Social Policy Research Centre of 1,157 workers in specialist family, domestic and sexual violence services indicated:

- A majority of workers wanted more training on how violence is experienced by LGBTQ+ people.

- Workers felt there was a lack of training and capacity to support LGBTQ+ communities.

- A general lack of societal knowledge and awareness more broadly of how violence occurs in gender diverse and same-sex relationships (Cullen et al. 2022).

Additionally, service providers may not recognise violence in LGBTQ+ relationships (Campo and Tayton 2015; Cortis et al. 2018; Cullen et al. 2022).

What are some of the barriers to seeking help?

'As I was in a lesbian relationship and my abuser was female, access to resources at the time was limited. Luckily, things have significantly improved in the last ten years and there is much more support available for those in LGBTIQA+ relationships who are experiencing family violence.'

Martina

Help seeking

The Private Lives 3 Survey asked respondents who had ever experienced violence from an intimate partner or family member about support-seeking behaviour from various services such as police, doctors, counselling services, sexual assault services or FDV services (see Table 1). Of respondents who reported having ever experienced family or intimate partner violence, 28% reported the most recent incident to a support service (Hill et al. 2020). The respondents who indicated that they had reported it to a service were also asked whether they felt supported by that service. Of the 886 respondents who reported the violence to a counselling service or psychologist, the vast majority (89%) felt supported, whereas of the 279 who reported the violence to police, less than half (45%) felt supported (Table 1).

| Service to which violence was reported the most recent time | Number | % | Felt supported (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Counselling service or psychologist | 886 | 18.7 | 89.4 |

Police (including LGBTIQ liaison officers) | 279 | 5.9 | 45.0 |

Doctor or hospital | 210 | 4.4 | 68.4 |

Lawyer, legal service, court system | 119 | 2.5 | 57.1 |

Telephone helpline | 117 | 2.5 | 58.6 |

Domestic or family violence service | 109 | 2.3 | 65.1 |

Employer | 80 | 1.7 | 71.3 |

Teacher or educational institution | 84 | 1.8 | 69.9 |

Sexual assault service | 44 | 0.9 | 79.6 |

LGBTIQ organisation | 46 | 1.0 | 73.9 |

Religious or spiritual community leader or elder | 37 | 0.8 | 64.9 |

Other | 206 | 4.4 | 84.3 |

I did not report this abusive behaviour | 3,406 | 72.0 | Not applicable |

Source: Hill et al. 2020.

Is it the same for everyone?

LGBTIQA+ people are a diverse group, and experiences of violence can occur in intersecting ways. National data are limited and data development is required to fully capture the scope of lived experience for LGBTIQA+ people, for example those who are also culturally and linguistically diverse people, or people with disability. Although limited, some data are available for people with disability, First Nations people, and people who live in rural Australia, which are discussed below.

LGBTIQA+ people with disability

Analysis of the Private Lives 3 study to examine the experience of FDSV among LGBTIQ adults with disability was performed with funding from Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability (Hill et al. 2022). There was not a sufficient number of respondents with disability with an intersex variation for the survey data to reflect their experiences.

The analysis found experiences of intimate partner or family violence were more common for LGBTQ+ adults with disability when compared with LGBTQ+ adults without disability. The proportion of LGBTQ+ adults with disability who had ever experienced intimate partner or family violence increased with the severity of disability:

- 73% of those with severe disability, 69% of those with moderate disability, and 67% of those with mild disability had ever experienced intimate partner violence, compared with 55% of LGBTQ+ adults without disability.

- 81% of those with severe disability, 78% of those with moderate disability, and 68% of those with mild disability had ever experienced violence from a family member (excluding their partner) compared with 56% of LGBTQ+ adults without disability (Hill et al. 2022).

Overall, family violence was more common among non-binary people (85%), trans men (84%) and trans women (78%) with disability, compared with cisgender women (77%) and cisgender men (70%) with disability. Broadly speaking, the proportion of LGBTQ+ adults with disability who had ever experienced intimate partner violence was similar across different gender identities (Hill et al. 2022).

First Nations LGBTIQA+ people

Significant diversity exists in gender identity, sexual orientation, sexual expression and lived experiences amongst First Nations LGBTIQA+ people. Brotherboys, Sistergirls and other First Nations LGBTIQA+ people may experience a number of significant and intersecting points of discrimination in Australia (HRSCSPLA 2021).

The Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) acknowledged First Nations LGBTI people may face specific difficulties in:

- maintaining cultural ties and family support which may contribute to FDSV

- gendered cultural initiation processes that are unable to accommodate an individual’s gender expression

- the gap between Aboriginal-specific service provision and service provision that accommodates for broader LGBTI populations and FDSV (AHRC 2015).

Additionally, there is a lack of research that recognises the importance of connection to land, culture, spirituality, ancestry, family and community, and how this may affect the individual, individual expression, and experiences of FDSV. See also Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

LGBTIQA+ people in regional and remote areas

Data are not currently available at a national level for LGBTIQA+ experiences of FDSV in regional and remote communities, but the particular risk and lack of support services for regional and remote communities and LGBTIQA+ people has been acknowledged (HRSCSPLA 2021).

Regional and remote communities face particular challenges as a whole, which may be heightened for LGBTIQA+ people experiencing FDSV. Access to LGBTIQA+ specific services that intersect with FDSV support is a critical area of development, particularly for regional and remote communities (DSS 2022).

The Private Lives 3 survey found that LGBTQ+ people residing in inner suburban locations experience lower levels of psychological distress, and better self-rated health than respondents in outer suburban areas, regional cities or towns or rural/remote locations (Hill et al. 2020). Further, a higher rate of respondents in urban areas accessed mental health services that were specifically LGBTIQ-inclusive compared with their peers in rural communities, which may reflect levels of availability (Hill et al. 2020).

For more information see Health services and Health outcomes.

Related material

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2021) Standard for sex, gender, variations of sex characteristics and sexual orientation variables, ABS website, accessed 28 March 2022.

ABS (2023a) Partner violence, ABS website, accessed 7 December 2023.

ABS (2023b) Personal safety, Australia methodology, 2021-22, ABS website, accessed 13 June 2023.

ABS (2023c) Sexual violence, 2021–22, ABS website, Australian Government, accessed 23 August 2023.

AHRC (Australian Human Rights Commission) (2015) Resilient individuals: sexual orientation, gender identity & intersex rights, National consultation report 2015, AHRC, Australian Government, accessed 9 June 2023.

AIFS (Australian Institute of Family Studies) (2022) LGBTIQA+ glossary of common terms, AIFS, Australian Government, accessed 9 June 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2018) Australia’s health 2018, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 9 June 2023.

AIHW (2019) Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 9 June 2023.

AIHW (2021) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on risk factor burden, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 22 June 2022.

Backhouse C and Toivonen C (2018) National Risk Assessment Principles for domestic and family violence: Companion resource. A summary of the evidence-base supporting the development and implementation of the National Risk Assessment Principles for domestic and family violence, ANROWS, accessed 9 April 2024.

Campo M and Tayton S (2015) Intimate partner violence in lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, intersex and queer communities: Practitioner resource, AIFS, Australian Government, accessed 15 August 2022.

Cortis N, Blaxland M, Breckenridge J, valentine k, Mahoney N, Chung D, Cordier R, Chen Y-W and Green D (2018) National survey of workers in the domestic, family and sexual violence sectors: Final report, Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW, accessed 9 June 2023.

Cullen P, Walker N, Koleth M and Coates D (2022) ‘Voices from the frontline: Qualitative perspectives of the workforce on transforming responses to domestic, family and sexual violence’ ANROWS (Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety) Research report, 21/2022, accessed 9 June 2023.

DSS (Department of Social Services) (2022) The National plan to end violence against women and children 2022-2032, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 9 June 2023.

eSafety (2020) Protecting voices at risk online, Office of the eSafety Commissioner, Australian Government, accessed 6 October 2022.

Haslam DM, Lawrence D, Mathews B, Higgins DJ, Hunt A, Scott JG, Dunne MP, Erskine HE, Thomas HJ, Finkelhor D, Pacella R, Meinck F and Malacova E (2023) 'The Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS), a national survey of the prevalence of child maltreatment and its correlates: methodology', Medical Journal of Australia, 218 (6 Suppl): S5-S12, doi:10.5694/mja2.51869.

Hegarty K, McKenzie M, McLindon E, Addison M, Valpied J, Hameed M, Kyei-Onanjiri M, Baloch S, Diemer K and Tarzia L (2022) “I just felt like I was running around in a circle”: Listening to the voices of victims and perpetrators to transform responses to intimate partner violence (Research report, 22/2022), ANROWS, accessed 9 April 2024.

Higgins DJ, Lawrence D, Haslam DM, Mathews B, Malacova E, Erskine HE, Finkelhor D, Pacella R, Meinck F, Thomas HJ and Scott JG (2024) ‘Prevalence of diverse genders and sexualities in Australia and associations with five forms of child maltreatment and multi-type maltreatment’, Child maltreatment, doi:10.1177/10775595231226331

Hill AO, Bourne A, McNair R, Carman M and Lyons A (2020) ‘Private Lives 3: The health and wellbeing of LGBTIQ people in Australia’, ARCSHS (Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society) Monograph Series 122, accessed 9 June 2023.

Hill AO, Amos N, Bourne A, Parsons M, Bigby C, Carman M and Lyons A (2022) Violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation of LGBTQA+ people with disability: a secondary analysis of data from two national surveys, ARCSHS, La Trobe University, accessed 9 June 2023.

HRSCSPLA (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs) (2021) Inquiry into family, domestic and sexual violence, Parliament of Australia, accessed 9 June 2023.

IHRA (Intersex Human Rights Australia) (2021) What is intersex?, IHRA website, accessed 9 June 2023.

Lawler S and Boxall H (2023) ‘Reporting of dating app facilitated sexual violence to the police: Victim-survivor experiences and outcomes’, Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice 662, accessed 9 June 2023.

Lusby S, Lim G, Carman M, Fraser S, Parsons M, Fairchild J and Bourne A (2022) Opening doors: Ensuring LGBTIQ-inclusive family, domestic and sexual violence services, ARCSHS, La Trobe University, accessed 9 April 2024.

Ovenden G, Salter M, Ullman J, Denson N, Robinson KH, Noonan K, Bansel P and Huppatz KE (2019) Sorting in Out: Gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer (GBTIQ) men’s attitudes and experiences of intimate partner violence and sexual assault, Sexualities and Genders Research, Western Sydney University and ACON, accessed 9 June 2023.

Szalacha LA, Hughes TL, McNair R and Loxton D (2017) Mental health, sexual identity, and interpersonal violence: Findings from the Australian longitudinal Women’s health study. BMC Women’s Health, 17(1):94, doi:10.1186/s12905-017-0452-5.

Teunissen C, Boxall H, Napier S and Brown R (2022) ‘The sexual exploitation of Australian children on dating apps and websites’, Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice 658, accessed 9 June 2023.

Wolbers H, Boxall H, Long C and Gunoo A (2022) ‘Sexual harassment, aggression and violence victimisation among mobile dating app and website users in Australia’, AIC (Australian Institute of Criminology) Research report 25, accessed 9 June 2023.

- Previous page People with disability

- Next page People from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds