Children and young people

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

On this page

Key findings What forms of FDSV affect children and young people? What do we know? How common are experiences of FDSV among children and young people? What are the responses to FDSV for children and young people? Impacts and outcomes of FDSV Has it changed over time? Is the experience of FDSV the same for everyone? Related materialKey findings

- 13% of adults in 2021–22 had witnessed partner violence against a parent before the age of 15.

- About 3 in 5 (59%) recorded sexual assault victims had an age at incident under 18 years in 2022.

- Among hospitalisations for FDV-related injuries in 2021–22, the most common perpetrator was parents among children aged 0–14, domestic partners for females aged 15–24 and other family members for males aged 15–24.

Children and young people are particularly at risk of experiencing the effects of family, domestic and sexual violence (FDSV). Violence to children and young people often occurs in homes and family settings. For children and young people who experience or are exposed to FDSV, the harm caused can be serious and long-lasting, affecting their health, wellbeing, education, and social and emotional development (Boxall et al. 2021; Campo 2015; DSS 2022; Toivonen and Backhouse 2018).

Experiences and exposure to FDSV can also increase the probability of the child or young person using violence in their home and later in life (Fitz-Gibbon et al. 2022; Ogilvie et al. 2022). This process can be referred to as the intergenerational transmission of violence, for further discussion, see Family and domestic violence.

This page presents the available national data and research on violence and abuse experienced by children and young people in the context of FDSV in Australia.

In AIHW reporting, ‘children’ are generally defined as people aged 0–12 and ‘young people’ as those aged 12–24. However, definitions can vary between legal frameworks, government policies and data sources. In some cases, data may not be available for certain age groups or the numbers may be too small for robust reporting. Therefore, different age groups may be used in reporting on children and young people, with children most commonly referring to people aged 0–14 years or 0–18 years and young people referring to people aged 15–24 or 19–24. Regardless of the age groups used for these terms, it is important to acknowledge that children develop at different rates and the term child can diminish the differences among young people’s capacity for and desire for self-determination (AIFS 2018).

What forms of FDSV affect children and young people?

In AIHW reporting FDSV refers to all forms of violence that occur in the context of family and intimate partner relationships, and sexual violence in any context (see What is FDSV?). Child abuse and neglect or child maltreatment includes any direct and indirect experiences of violence or neglect among young people aged under 18 years by a person in a position of responsibility, trust or power over the child or young person. This may involve violence used by related or unrelated adults, young people or other children (AIFS 2018; WHO 2022).

Direct forms of FDSV

Direct forms of FDSV include those in which the child or young person is the direct target of FDSV, which may be through neglect, physical, sexual and emotional violence or abuse, and sexual harassment (see Box 2).

A person may experience multiple and overlapping forms of FDSV including:

- Physical violence or abuse – the intentional attempt, use or threat of physical force with the intent to harm or frighten a person (ABS 2023d).

- Sexual violence or abuse – any act or attempted act of a sexual nature without consent or threat of sexual acts. Any sexual acts with a person under the age of consent are considered sexual abuse. Note that the age of consent varies between jurisdictions (see Consent) (ABS 2023d; DSS 2022).

- Sexual harassment – unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature which makes a person feel offended, humiliated and/or intimidated, where a reasonable person would anticipate that reaction in the circumstances (ABS 2023d; DSS 2022).

- Emotional violence or abuse – behaviours or actions that are perpetrated with the intent to manipulate, control, isolate or intimidate, and which cause emotional harm or fear (ABS 2023d).

- Neglect – any serious acts, omissions or patterns of behaviour, intentional or not, that result in a dependent child or young person not receiving essentials for healthy physical and emotional development (AIFS 2018).

See also What is FDSV?

Technology can be misused to support the perpetration of different forms of violence, such as harassment, stalking, and sexual violence. The term, technology-facilitated abuse, is used to refer to any abusive behaviours and activities that also involve the use of technology such as phones, internet-enabled devices and online platforms (Dragiewicz et al. 2020; Powell et al. 2022).

Indirect forms of FDSV

Indirect forms of FDSV (or exposure to FDSV) occur among children and young people when they are exposed to the obvious and/or subtle acts of violence directed at people around them, most commonly someone they live with. Exposure to FDSV can include:

- seeing and/or hearing acts of physical and sexual violence and/or its effects

- witnessing patterns of non-physical controlling behaviours, for example, a parent belittling, disregarding or limiting the freedom of another parent (see also Coercive control) (Campo 2015; Katz et al. 2020).

What do we know?

Factors related to experiencing FDSV

Many factors that are more common among people who have experienced FDSV than those who have not (risk factors) are also associated with experiences of FDSV among children and young people, see Factors associated with family, domestic and sexual violence. While there is a statistical association between risk factors and experiences of FDSV, this does not mean these factors cause FDSV. Risk factors that are unique to or may have a stronger association among children and young people include:

- parental/caregiver factors – including a parent’s substance abuse, parental separation or divorce, poor mental and physical health and low levels of education or income

- family factors – including large size, economic hardship, patterns of conflict or violence, involvement in criminal behaviour and actual or intended separation of parents

- individual factors – including low birth weight, disability, pregnancy or birth complications (AIFS 2017; CDC 2022; Fazel et al. 2018; Higgins et al. 2023; Toivonen and Backhouse 2018).

As is the case for people in most age groups, FDSV among young people is more likely to be experienced by young women than young men. This gendered pattern, while present, is less apparent among children, with no gendered pattern evident for exposure to domestic violence (DSS 2022; Mathews et al. 2023b). For a discussion of FDSV centred on the experiences of young women, see Young women.

There are some factors that have been associated with a decreased likelihood that children and young people will have experienced FDSV (protective factors), including, but not limited to:

- strong parent/child relationships

- family cohesion and support networks

- parental education, employment, resilience and understanding of child development (AIFS 2017; CDC 2022).

Barriers to accessing help

Children and young people may experience many barriers to accessing help that are shared with the general population including, but not limited to, the fear of not being believed, restrictive cultural norms and previous negative experiences with the police and legal systems (AIFS 2015; Coumarelos et al. 2023; RCIRCSA 2017). Some surveys have found that many people in Australia hold attitudes that discredit or distrust children and young people’s disclosures of abuse and violence (Tucci and Mitchell 2021; Coumarelos et al. 2023). For example, an online survey with a sample of about 1000 people aged 18 years and over in Australia that was weighted to be nationally representative found that 67% of respondents believed that children make up stories about being abused or are uncertain whether to believe children when they disclosed being abused (Tucci and Mitchell 2021).

Barriers that are specific to children and young people or may have a larger effect among them include:

- fear of withdrawal of support

- perceived or actual reliance on the perpetrator of violence (for example, when abuse is perpetrated by a parent)

- a lack of understanding or recognition of the abuse or its seriousness

- being unable to express or communicate the abuse

- a lack of appropriate institutional (for example, schools) or child and young people-specific supports (AIFS 2015; Alaggia et al. 2019; Humphreys and Healey 2017; RCIRCSA 2017).

For a further discussion of barriers, see How do people respond to FDSV?, and for a discussion of community attitudes to FDSV, see Community attitudes.

Negative effects on health and wellbeing

Experiences of and exposure to FDSV as a child or young person can have both immediate and lifelong negative effects on the health, wellbeing, development and life satisfaction of victim-survivors. Experiences of FDSV can negatively impact everyone connected to the victim-survivor through physical, emotional, financial, social and psychological effects. Both victim-survivors and their connections can be affected by a loss of trust in people, hyper-vigilance and a loss of connection to their communities. Interactions with services can often be re-traumatising, especially in cases of inadequate justice and support service responses (C3P 2017; DSS 2022; Jones et al. 2021).

Maternal experiences of and exposure to FDSV as a child or young person are statistically associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. These include low birth weight and pregnancy or birth complications, which in turn, are risk factors for experiencing FDSV among children and young people. This demonstrates the intergenerational impacts of FDSV (see also Family and domestic violence and Pregnant people) (Mamun et al. 2023).

For information related specifically to the outcomes of child sexual abuse, see Child sexual abuse.

How does FDSV affect children long-term?

'Children from families experiencing family violence end up having to recover from their childhood in their adult years. The unaddressed trauma from navigating an unhealthy, abusive parent gets carried into their own relationships often leading to unhealthy coping behaviours, and the continuation of the intergenerational cycle of violence.'

Lily

Measuring the extent of violence against children and young people

It is difficult to obtain robust data on children’s experiences of FDSV. Due to the sensitive nature of this subject, most large-scale population surveys focus on adults. However, estimates of adults from surveys are likely to underestimate the true extent of FDSV due to some people’s reluctance to disclose information and reliance on participants’ recollections of events, which may have changed over time.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Personal Safety Survey (PSS) asks people aged 18 and over (adults) about experiences of FDSV within specified timeframes (such as before and since the age of 15, in the last 12 months, and in the last 2 years). Data related to experiences of physical and sexual abuse perpetrated by an adult before the age of 15 and experiences of witnessing parental violence before the age of 15 do not provide estimates of the current prevalence of abuse experienced by children (ABS 2023c). For more information about the PSS, please see What is FDSV? and Data sources and technical notes.

The 2021 Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS) was a cross-sectional survey of people aged 16 and over about their experiences of child sexual abuse and child maltreatment from a parent or caregiver. It also assessed some other childhood adversities and associations with aspects of health and wellbeing later in life. These data provide information about those who responded to the survey and we have restricted our discussion to this group. We have not used these data to draw conclusions about the Australian population given the response rate (see Box 3). However, the survey does provide important information about the survey respondents, which can inform the work of researchers, advocates, and policy makers.

Due to differences in the methods used, findings from these sources are not comparable. For more information about the differences in design and scope, concepts, and definitions for these sources, please refer to the ABS Technical note: Personal Safety Survey and the Australian Child Maltreatment Study.

What national data are available to report on FDSV among children and young people?

Data are available across a number of surveys and administrative data sources to look at the experience, service responses and outcomes of FDSV among children and young people.

- ABS Personal Safety Survey

- ABS Recorded Crime – Victims

- AIC National Homicide Monitoring Program

- AIHW Australian Burden of Disease Study

- AIHW Child Protection National Minimum Data Set

- AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database

- AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services (SHS) collection

- Australian Child Maltreatment Study

- The National Survey of Secondary Students and Sexual Health

- The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children.

For more information on these data sources, please see Data sources and technical notes.

How common are experiences of FDSV among children and young people?

-

13%

of adults in 2021–22

had witnessed partner violence against a parent before the age of 15

Source: ABS Personal Safety Survey

The PSS asks respondents about whether they had witnessed violence towards their own parents when they were children. These data are collected from adults 18 years and over about the violence they witnessed before the age of 15.

According to the 2021–22 PSS, about 1 in 8 (13% or 2.6 million) people, aged 18 years and over, witnessed violence towards a parent by a partner before the age of 15. A higher proportion of people had witnessed partner violence against their mothers (12%, or 2.2 million) than their fathers (4.3%, or 837,000). Of people who had witnessed violence towards their mother, almost 3 in 4 (72% or 1.6 million) had witnessed the violence on more than 2 occasions (ABS 2023a). See also Family and domestic violence and Intimate partner violence.

-

18% of women

11% of men

in 2021–22 had experienced physical and/or sexual abuse before the age of 15

Source: ABS Personal Safety Survey

The PSS also collects data on experiences of physical and/or sexual abuse (abuse) before the age of 15 among females and males aged 18 and over (women and men) and whether perpetrators were known or strangers. The PSS found that about 1 in 6 women (18%, or 1.7 million) and 1 in 9 men (11%, or 1.0 million) in 2021–22 had experienced abuse before the age of 15 (ABS 2023a).

Of the 989,000 women and 788,000 men who had experienced childhood physical abuse, the most common perpetrator of the first incident was a family member, with the majority involving a parent:

- 89% for women, with 52% perpetrated by their father or step-father and 36% by their mother or step-mother

- 87% for men, with 56% perpetrated by their father or step-father and 32% by their mother or step-mother (ABS 2023a).

For the available data on the experiences of sexual abuse before the age of 15, see Child sexual abuse.

Estimates from the 2021–22 PSS indicate that people who had witnessed parental violence or experienced childhood physical and/or sexual abuse were more likely to have experienced violence since the age of 15 when compared with those who had not had childhood experiences of violence or abuse.

The experience of partner violence (physical and/or sexual violence, emotional abuse or economic abuse by a partner they lived with, or had lived with, in a married or de facto relationship), occurred among:

- 43% (or 1.1 million) of people who had witnessed parental violence before the age of 15, compared with 18% (or 3 million) of people who had not witnessed parental violence

- 43% (or 1.2 million) of people who had experienced physical and/or sexual abuse before the age of 15, compared with 17% (or 2.8 million) of people who had not experienced childhood abuse (ABS 2023a).

See also Intimate partner violence.

Experiences of maltreatment as a child

The 2021 ACMS collected data on experiences of maltreatment as a child (person under 18 years) (see Box 3). The study indicated for surveyed people aged 16 years and over in 2021:

- about 3 in 10 (29%) had experienced sexual abuse from any person – about 1 in 12 (8.7%) people experienced forced sex (rape) in childhood

- about 3 in 10 (31%) had experienced emotional abuse from a parent/caregiver, with 80% of these people reporting the abuse occurred over years

- about 1 in 11 (8.9%) had experienced neglect from a parent/caregiver, with 75% of these people reporting the neglect occurred over years

- 2 in 5 (40%) had experienced exposure to domestic violence (EDV) between a parent/caregiver and their partner, with 32% of these people reporting more than 50 incidents (Haslam et al. 2023c; Higgins et al. 2023; Mathews et al. 2023b).

The most recent ACMS report does not provide data about specific perpetrators, however, analyses related to this and other topics are expected in future ACMS reports. See Child sexual abuse for a discussion of the ACMS findings about perpetrators of child sexual abuse.

For more information about this study, see Children and young people: Measuring the extent of violence against children and young people and Data sources and technical notes.

The ACMS was a cross-sectional survey of just over 8,500 participants aged 16 years and over between 9 April and 11 October 2021. People were considered to be eligible for participation if they were aged 16 years or more, in an age group for which participants were required when contacted and had sufficient English language proficiency for participation. The final response rate was 4.0% when based on the estimated number of eligible participants (about 210,000 people) and 14% when based on eligible participants contacted (about 60,800 people) (Haslam et al. 2023a).

Retrospective self-report data was collected exclusively via computer assisted mobile phone interview using a well-validated questionnaire that was adapted to measure child maltreatment in an Australian cultural context (see Data sources and technical notes). While the ACMS did not exclude First Nations people (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people), it was determined that it was not ethically or methodologically appropriate to disaggregate data by Indigenous status for this survey (Haslam et al. 2023a, 2023b; Mathews et al. 2021).

The ACMS defines a child as a person aged under 18 years (Haslam et al. 2023a). The ACMS measured five types of child maltreatment with the following definitions:

- Physical abuse – experiences of physical force used by an adult against a child that result, or have a high likelihood of resulting, in injury, pain, or a breach of dignity.

- Sexual abuse – any contact and non-contact sexual act, or attempted act, inflicted on a child by a person where the child either lacks capacity to give consent, or has capacity but does not give full, free, and voluntary consent. Sexual harassment was excluded from estimates of sexual abuse.

- Emotional abuse – non-physical interactions between a child and parent or caregiver that make the child feel worthless, flawed, unloved, unwanted, endangered or only of value in meeting another’s needs. Emotional abuse was considered to have occurred if such experiences occurred over a period of at least weeks.

- Neglect – involves the failure by a parent or caregiver to provide a child with the basic necessities of life. Neglect was considered to have occurred if such experiences occurred over a period of at least weeks. Neglect has several dimensions: medical, educational, supervisory, physical, nutritional, and environmental.

- Exposure to domestic violence – occurs when a child sees or hears one parent/caregiver behave in certain ways towards their partner including: physical acts of violence; serious threats of harm; intimidating, controlling and isolating behaviours; and damage to property and pets during an argument (Mathews et al. 2023a).

The ACMS also conducted assessments for other childhood adversities including corporal punishment, internet sexual victimisation, generalised sexual harassment, peer bullying, sibling victimisation, out of home care, and family-related adversities (Haslam et al 2023a).

Figures presented from the ACMS have been rounded. For exact figures, please see the cited primary source.

For more information about this study, see Children and young people: Measuring the extent of violence against children and young people and Data sources and technical notes.

Partner violence experienced by young people

The PSS defines a partner as a person the respondent lives with or lived with at some point in a married or de facto relationship (ABS 2017b, 2023a).

The latest available estimates of experiences of partner violence among women aged 18–24 are provided by the 2021–22 PSS. Estimates are not available for men aged 18–24 as 2021–22 data are not sufficiently statistically reliable for reporting. The 2016 PSS (which had estimates for both men and women) showed that among people aged 18–24, most partner violence is experienced by women (AIHW 2022a).

Among women aged 18–24, in the 2 years prior to 2021–22:

- about 22,700* (2.2%*) experienced partner physical and/or sexual violence

- about 29,200* (2.9%*) experienced emotional abuse by a partner

- about 26,100* (2.6%*) experienced economic abuse by a partner (ABS 2023b).

Note that estimates marked with an asterisk (*) should be used with caution as they have a relative standard error between 25% and 50%. For the PSS definitions of physical or sexual violence and emotional abuse, see Data sources and technical notes.

Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) is an ongoing national study following the development of 10,000 children and their families from all parts of Australia. The sample was nationally representative of all Australian children at recruitment. The Australian Institute of Family Studies examined intimate partner violence (IPV) victimisation among people aged 18-19 in Australia using data from the LSAC K cohort at Wave 8, which were collected in 2018. The report found that among the 3,000 participants aged 18-19 who completed the Wave 8 survey, around 3 in 10 (29%) reported at least one experience of IPV in the year before the survey. Specifically:

- 1 in 4 (25%) experienced emotional abuse

- 1 in 8 (12%) experienced physical violence

- 1 in 12 (8%) experienced sexual abuse in the previous year.

Women aged 18-19 (11%) were more likely to be victim-survivors of sexual abuse than men of the same age (4%). The rates of emotional abuse and/or physical violence victimisation were similar between young women and men.

The report also identified supportive friendships and high trust and good communication with parents during adolescence as protective factors that reduce the risk of IPV.

Please see Data sources and technical notes for more information on the LSAC.

Source: O’Donnell et al. 2023.

Sexual violence experienced by young people

The latest available estimates of sexual violence and sexual harassment among women aged 18–24 are provided by the 2021–22 PSS, while the latest estimates for men aged 18–24 are provided by the 2016 PSS.

About 1 in 10 (11%, or 113,000) women aged 18–24 experienced sexual assault in the 2 years prior to 2021–22, more than any other age group.

People aged 18–24 are more likely than other age groups to have experienced sexual violence and sexual harassment (ABS 2017b, 2023h, 2023i).

Based on the latest PSS data (2021–22) on experiences of sexual violence and harassment among women aged 18–24:

- about 126,000 (12%) women aged 18–24 experienced sexual violence in the 2 years prior to 2021–22, with about 113,000 (11%) women experiencing sexual assault (ABS 2023i)

- about 356,000 (35%) women aged 18–24 experienced sexual harassment in the 12 months prior to 2021–22 (ABS 2023h).

Based on the latest PSS data (2016) on experiences of sexual violence and harassment among men aged 18–24:

- about 26,400* (2.3%) men aged 18–24 experienced sexual violence in the 12 months prior to 2016, which compares with 65,100 (5.9%) women aged 18–24 during the same period

- about 185,000 (16%) men aged 18–24 experienced sexual harassment in the 12 months prior to 2016, which compares with 421,000 (38%) women aged 18–24 during the same period (ABS 2017b).

Note that estimates marked with an asterisk (*) should be used with caution as they have a relative standard error between 25% and 50%. For the PSS definitions of sexual violence and sexual harassment, see Data sources and technical notes.

Sexual violence experienced by university and secondary school students

Data about sexual harassment and sexual assault at Australian universities are available from the National Student Safety Survey (NSSS) (see Data sources and technical notes for the NSSS definitions of sexual harassment and assault). The 2021 NSSS included a sample of about 43,800 students aged 18 and over from 38 universities who volunteered to respond to the online survey. The sample was weighted to be representative of students studying at Australian universities aged 18 years and over. The NSSS found that, in the 12 months prior to 2021, in an Australian university context, younger students (aged 18–21) were more likely to have experienced:

- sexual harassment (12%), when compared with those aged 22–24 years (8.4%), 25–34 years (5.5%) or older, with those aged 18–21 also more likely to report incidents in student accommodation or residences (16%)

- sexual assault (1.9%) compared with those aged 22–24 years (1.1%), 25–34 years (0.5%) or older (Heywood et al. 2022).

For further discussion of the NSSS, see Sexual violence.

The 7th National Survey of Secondary Students and Sexual health in 2021 investigated some key issues related to sexual harassment and violence among secondary school students including experiences of unwanted sex and the sharing of sexual images, video and messages (sexting) (see Box 5).

The 7th National Survey of Australian Secondary Students and Sexual Health (SSASH survey) conducted in 2021 surveyed about 6,800 secondary school students aged 14–18 years. The SSASH survey is not considered representative of all secondary school students aged 14–18 as it used a convenience sample based on voluntary survey completion and online recruitment and completion.

For definitions and other technical details about this data source, please see Data sources and technical notes.

Experiences of unwanted sex by secondary school students

The SSASH survey asked students about whether they had ever had sex when they did not want to, the context and circumstances of the experience/s and whether they sought help.

About 2 in 5 (40%) respondents who had ever experienced sex had also experienced unwanted sex during their life. Experiences of unwanted sex were more common among respondents that were:

- trans and non-binary young people (55%) and young women (45%) than young men (21%)

- LGBQ+ young people (48%) than heterosexual young people (34%).

The average age at which unwanted sex was first experienced was 14.9 years, lower for respondents that were trans and non-binary young people (14.0 years) compared with young women (15.0 years) and men (15.4 years). About 1 in 5 (21%) were younger than 14 years of age.

Most respondent’s first experience of unwanted sex occurred in an intimate relationship (60%). About 1 in 5 (21%) were in familial or friendship relationships and for about 1 in 10 (9.9%) it was perpetrated by someone known but not a friend or family member. Respondents described the context in which their most recent experiences of unwanted sex occurred:

- about 2 in 3 (65%) young people described experiencing verbal pressure

- about 2 in 5 (41%) said they agreed to sex as they were worried about the negative outcomes of not having sex

- about 1 in 3 (32%) were physically forced to have sex

- about 3 in 10 (28%) indicated they were too drunk or high at the time to consent to sex.

About 1 in 4 (23%) respondents who had experienced unwanted sex had talked to someone or sought help about their experience.

The percentage of respondents in year 10 and year 12 with unwanted sexual experiences has varied between 25% and 29% between 2002 and 2018, increasing to 41% in 2021. It is currently unclear why the percentage increased, although it may reflect an increasing awareness of sexual violence and consent among young people.

Experiences of sexting and image-based abuse

Sharing sexual images, video and sexually suggestive messages (sometimes collectively referred to as ‘sexting’) can be a part of sexual communication and relationships. It can also put someone at risk of abuse, including the non-consensual sharing of images (image-based abuse) and pressure through threats of image-based abuse (eSafety Commissioner 2022).

The SSASH survey found that many respondents had experienced sexting, with over 4 in 5 (86%) reporting that they had received sexual messages or images and over 2 in 3 (71%) that they had sent them before. In questions related to consent and sexting:

- about 1 in 3 (29%) reported that they had been sent a sexual or nude image that they had not asked for and did not want to receive on at least one occasion

- about 1 in 5 (18%) reported that sexual photos of them had been shared without their permission on at least one occasion (unwanted sharing) – young women (21%) and trans and non-binary young people (19%) were more likely to report this than young men (11%).

Most respondents agreed or strongly agreed that you have to be careful about sexting (96%) and that sending photos may have serious negative consequences (92%). However, many felt there were positive aspects to sexting such as being more open about sex and sexuality (65%) and that ‘sexting is a regular part of a relationship’ (63%)

See Consent for further discussion of consent.

Source: Power et al. 2022.

Sexual harassment in the workplace

Data related to experiences of sexual harassment in workplaces are available from the 2022 Australian Human Rights Commission’s national survey on sexual harassment in workplaces (see Box 6).

The Australian Human Rights Commission’s national survey on sexual harassment in workplaces sampled about 10,200 people aged 15 and over using non-probability, quota sampling methods and weighting to obtain a sample representative of the population aged 15 and older by sex, age and area of residence.

In this survey, sexual harassment also included behaviours more commonly reported as sexual violence, such as rape or sexual assault. There was only a small number of respondents aged 15–17 (n<50) so results should be interpreted with caution.

Source: AHRC 2022.

More people aged 15–17 (47%) or 18–29 (46%) in 2022 had been sexually harassed in their workplace in the previous 5 years when compared with the total population (33%). Young women were more likely than young men to report sexual harassment:

- 60% of women and 25% of men aged 15–17 years

- 56% of women and 35% of men aged 18–29 years (AHRC 2022).

For more information on sexual harassment and sexual violence, see Sexual violence and for a discussion of FDSV centred on the experiences of young women, see Young women.

Technology-facilitated abuse among children and young people

Most Australian children and young people have ready access to the internet and digital technology. However, there is no nationally-representative data on the prevalence of technology-facilitated abuse among children.

A non-representative national survey in 2019 of 515 professionals who work on family and domestic violence (FDV) cases asked some questions related to experiences of technology-facilitated abuse among children. This found that:

- about one-quarter (27%) of FDV cases the professionals dealt with involved technology-facilitated abuse of children

- common forms of abuse included monitoring and stalking, threats and intimidation and blocking communication

- everyday technologies were used in abuse such as mobile phones, texting and Facebook

- many of the children experienced mental health issues (67% of cases), fear (63%), and negative impacts on their relationship with the non-abusive parent (59%) (Dragiewicz et al. 2020).

-

72% of surveyed people aged 18-24

in 2022 had experienced technology-facilitated abuse in their lifetime, more than any other age group

Source: ANROWS Technology-facilitated abuse: National survey of Australian adults’ experiences

Data on the prevalence of technology-facilitated abuse among young people aged 18–24 are available from a nationally representative survey of about 4,600 adults in 2022. The survey used random probability-based sampling methods and weighting to allow results to be generalised to the adult Australian population (Powell et al. 2022). This survey estimated that among young people aged 18–24 years:

- about 5 in 7 (72%) have experienced technology-facilitated abuse in their lifetime, the highest proportion of any other age group

- young women (74%) are more likely than young men (68%) to have experienced technology-facilitated abuse in their lifetime

- about 2 in 5 (38%) young people have perpetrated technology-facilitated abuse in their lifetime, the second highest proportion of any age group (Powell et al. 2022).

While the increased use of mobile dating apps and websites over the past 10 years has allowed many people to build relationships, studies have suggested that experiences of technology-facilitated sexual violence are common for people who use these online spaces, particularly women and members of LGBTIQA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer, asexual people, or people otherwise diverse in gender, sex or sexual orientation) communities (Wolbers et al. 2022). However, there is no research that specifically relates to prevalence among young people. For further discussion, see Stalking and surveillance.

Technology-facilitated abuse also includes the possession, production and distribution of pictures and video that capture child sexual abuse (child sexual abuse material [CSAM]). With increases in the global availability of the internet, CSAM has continued to grow as a global issue. However, there is limited information on its effects on children and young people in Australia (see Child sexual abuse).

Corporal punishment

About 3 in 5 (58%) surveyed young people aged 16–24 in 2021 self-reported experiencing corporal punishment 4 or more times in childhood.

Corporal punishment is the use of physical force with the intention of causing a child or young person to experience pain or discomfort to change or punish their behaviour. Research has shown that corporal punishment can negatively impact children and young people’s development, health and wellbeing in both the short- and long-term and is minimally effective in the short-term and not effective in the long-term (Sege and Siegel 2018; Poulsen 2019).

The 2021 ACMS found that about:

- 3 in 5 (58%) young people aged 16–24 self-reported experiencing corporal punishment 4 or more times in childhood

- 1 in 2 (54%) parents surveyed had used corporal punishment with their own children

- 1 in 4 (26%) people believe corporal punishment is necessary to raise children, with a higher proportion of older people than younger people holding this belief – the highest proportion was among those aged 65 and over (38%) and the lowest among those aged 16–24 (15%) (Havighurst et al. 2023).

For more information about this study, see Children and young people: Measuring the extent of violence against children and young people and Data sources and technical notes.

There are no national data available on the use of other aversive disciplinary strategies such as yelling at and shaming children.

What are the responses to FDSV for children and young people?

There are many formal and informal responses and supports which may be used by people who experience family and domestic violence, including family and friends, health professionals and helplines. However, national data related to children and young people is not available for all responses.

The First National Action Plan for the National Strategy to Prevent and Respond to Child Sexual Abuse includes an action for the AIHW to develop a scoping study for and establish an Australian Child Wellbeing Data Asset, a national, child-focused, linked data set. The data asset would support the analysis of children and young people’s pathways through government services (for example, education, health services, child protection, youth justice, mental health services, hospitals, police services) for which there is currently no national data (DPMC 2021).

On this topic page we present the available national data on responses to FDSV for children and young people.

Helplines and related support services

There are a number of general and specialised helplines in Australia that provide information, advice and support to children and young people who are experiencing or at risk of FDSV. See Helplines and related support services for a discussion of such services including but not limited to:

- Kids Helpline, a free national helpline that provides support for children and young people aged 5 to 25

- Bravehearts, a support service for people affected by child sexual abuse and a National Redress Scheme service provider (Bravehearts 2021)

- Blue Knot Foundation, a support service for people affected by complex trauma and a National Redress Scheme service provider (Blue Knot Foundation 2021).

Help seeking behaviours

Apart from data related to helplines and support services, there is no national data on help seeking behaviours among children currently available.

The PSS collects data for young people aged 18–24 on advice or support (help) sought and received after the most recent experience of family and domestic violence. However, there are data quality issues and limitations in reporting for this age group due to the number of people sampled in the survey. Only data of a sufficient quality is reported below.

Based on data from the 2016 PSS, in response to their most recent incident of violence perpetrated by an intimate partner or family member the proportion of women aged 18–24 who:

- sought help was over half (54% or 49,100) of those sexually assaulted by a male*

- sought help was about two-thirds (64% or 102,000) of those physically assaulted by a male

- did not seek help was about 1 in 4 (27% or 13,700) of females physically assaulted by a female (ABS 2017a).

Noting that statements marked with a * have a 95% margin of error greater than 10 percentage points, which should be considered when using this information.

The ACMS collected data about people aged 16 and over who had experienced child maltreatment and their contact with health providers over the 12 months before the survey. People who had experienced child maltreatment were more likely than those who had not to have engaged all types of health service professionals assessed in the survey and to be admitted to hospital with mental health problems (Pacella et al. 2023). In the 12 months before the survey, people who had experienced child maltreatment were more likely than those who had not to have:

- seen a psychiatrist (3.0 times)

- consulted a mental health nurse (2.7 times)

- had 6 or more visits to a GP (2.4 times)

- been admitted for a mental disorder (2.4 times)

- had 24 or more visits with any health practitioner (2.3 times)

- had 12 or more visits with any health practitioner (1.8 times)

- had an overnight hospital admission (1.4 times) (Haslam et al. 2023c).

Even higher associations were present for people who had experienced multi-type maltreatment (Haslam et al. 2023c).

For more information about this study, see Children and young people: Measuring the extent of violence against children and young people and Data sources and technical notes.

Child protection services

In Australia, states and territories are responsible for providing child protection services to anyone aged under 18 who has been, or is at risk of being, abused, neglected or otherwise harmed, or whose parents are unable to provide adequate care and protection.

The latest data on child protection services in Australia show that:

- about 1 in 32 (3.1% or more than 180,000) children came into contact with the child protection system in 2022–23

- almost 3 in 5 (57% or about 25,800) children who were the subject of a child protection substantiation in 2022–23 had emotional abuse recorded as the primary type of abuse or neglect (AIHW 2024b).

See Child protection for an in-depth discussion.

Police responses

To report on the police response to FDSV this report uses the ABS Recorded Crime collections, which are based on crimes that are reported to police in each state and territory (see Box 7 for key data considerations).

Recorded Crime – Victims data do not represent a count of individual people as one person can be counted multiple times if they experience multiple incidents of a specific crime and/or multiple different crime offences. Counts are also randomly adjusted to avoid the release of confidential data. Discrepancies may occur between sums of the component items and totals (ABS 2023g).

Not all offences are reported to police, which means recorded crime data underestimate FDSV in Australia. The PSS collects data on reporting levels to police and reasons for not contacting police after instances of FDSV, see FDV reported to police and Sexual assault reported to police for further discussion.

Generally, the age of victims is reported as the age victims were when they first became known to the police (age at report), however, some sexual assault data are explored by age at incident. For sexual assault, there can be more variability in the time to report crimes to police than other crimes. This means the age at incident for sexual assault can differ from age at report (ABS 2023g).

Offences are described as FDV-related where the relationship of offender to victim, as stored on police recording systems, falls within a specified family or domestic relationship, or where a FDV flag has been recorded following a police investigation. Relationship of offender to victim data for Western Australia is not of a sufficient quality for national reporting (ABS 2023g).

Changes in recorded crime data over time may be due to changes in reporting behaviour, increased awareness about forms of violence, changes to police practices, an increase in incidents and/or a combination of these factors. For detailed technical notes, see FDV reported to police and Sexual assault reported to police.

Also, refer to the ABS Recorded Crime – Victims methodology website- external site opens in new window for further information.

It is not possible to summarise data for all recorded crimes related to FDSV as recorded crime data are collected based on specific criminal offences and there is variability in the collection methods and classification of offences and FDV between states and territories. This means that some data are not available for all states and territories (see Data sources and technical notes). In this section we discuss the available data by offence type.

Recorded sexual assault offences

-

3 in 5

recorded sexual assault victims had an age at incident under 18 years in 2022

Source: ABS Recorded Crime - Victims

Based on national data, about 3 in 4 (74%) recorded sexual assault victims had an age at incident under 25 years in 2022:

- most were aged under 18 years (59% of all victims, or about 18,900 victims)

- about 1 in 7 were aged 18–24 years (15% of all victims, or about 4,900) (ABS 2023e).

Among recorded sexual assault victims with an age at incident under 25 years:

- about 5 in 6 were female (82%, or about 19,500)

- over half were aged 10–17 years (56%, or about 13,400)

- fewer than 2 in 5 were victims of FDV-related sexual assault (36%, or about 8,500) (ABS 2023e).

Most recorded FDV-related sexual assault victims in 2022 with an age at incident under 25 years were female (87%, or about 7,400). Among those aged 0–24, the most common age group for:

- female victims was 10–17 years (49%, or about 3,700)

- male victims was 0–9 years (61%, or about 680) (see Supplementary tables).

Based on 2022 data (excluding Western Australia), offenders of sexual assault crimes were known to most recorded victims with an age at incident of 0–9 years (87%), 10–17 years (79%) and 18–24 years (63%). In between 3.9% and 6.9% of cases, a perpetrator wasn’t able to be identified or a relationship was not specified (ABS Recorded Crime – Victims, unpublished).

The most common relationship of offender to victim by age at incident were:

- family for victims aged 0–9 years (57%), with 21% involving parents

- people who were known but not family members for victims aged 10–17 years (49%) and 18–24 years (37%) (ABS Recorded Crime – Victims, unpublished).

Strangers accounted for about 3 in 10 (31%) offenders of victims with an age at incident of 18–24 years, with smaller proportions among younger age groups (ABS Recorded Crime – Victims, unpublished).

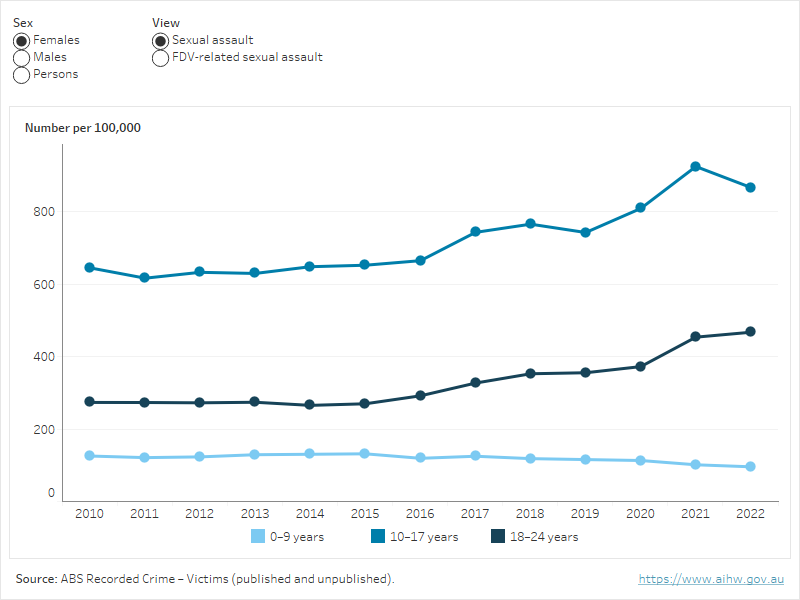

Changes over time in the rate of both recorded sexual assault and FDV-related sexual assault victims have varied by age at report:

- among victims aged 10–17 years and 18–24 years, the rate has increased

- among victims aged 0–9 years, the rate decreased among sexual assault victims and remained similar among FDV-related sexual assault victims (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Rate of recorded sexual assault and FDV-related sexual assault victims, by sex and age at report, 2010–2022

Figure 1 shows the victimisation rate of recorded sexual assault and FDV-related sexual assault victims aged 0–9, 10–17 and 18–24 years by sex from 2014 to 2022.

Recorded victims of other FDV-related offences

FDV-related assaults

Based on data on recorded FDV-related assault victims by age at report in 2022 (excluding Victoria and Queensland, see Data sources and technical notes):

- over 1 in 4 (27% or about 20,900) were under 25 years, with most aged 18–24 (about 12,300)

- there were over 3 times as many female victims (about 9,300) as male victims (about 2,900) for those aged 18–24

- there were more male victims (about 1,200) than female victims (about 820) for those aged 0–9 (ABS 2023e).

In states and territories where data are available (see Data sources and technical notes), the most common relationship of offender to victim in 2022 by age at report was:

- parent for male and female victims aged 0–9, except male victims in the Northern Territory for whom family other than parents was more common

- parent for male and female victims aged 10–17, except female victims in Tasmania and the Northern Territory for whom intimate partner was more common and male victims in the Northern Territory for whom family other than parents was more common

- intimate partner for male and female victims aged 18–24 (see Supplementary tables).

FDV-related kidnapping/abduction

In 2022, about 54% (or about 275) of all kidnapping/abduction offences involved victims with an age at report of under 25 years. Among victims under 25 years, over 1 in 4 (27% or about 75) are victims of FDV-related kidnapping/abduction. Based on data excluding Western Australia, the most common relationship of offender to victim of FDV-related kidnapping/abductions in 2022 by age at report was:

- parents for victims under 18 years

- intimate partners for victims aged 18–24 (ABS Recorded Crime – Victims, unpublished).

Recorded FDV-related kidnapping/abduction victims have varied year to year with no apparent trend over time (ABS Recorded Crime – Victims, unpublished). Due to the low number of offences, any change year to year can result in a large proportional change in the victimisation rate making changes over time difficult to interpret.

See FDV reported to police and Sexual assault reported to police for a discussion of the general population.

Hospitalisations

Children aged 0–14 years in 2022–23 had the highest proportion of hospitalisations for injuries from assault that were FDV-related compared with any other age group (AIHW 2024a).

Among injury hospitalisations in 2022–23 where the perpetrator was specified, the injury was FDV-related for:

- over half (54%, or about 295) of children aged 0–14 years, with about 125 girls and 170 boys

- over 1 in 3 (35%, or about 370) young people aged 15–19 years, with about 275 females and 93 males

- almost half (46% or about 690) young people aged 20–24 years, with about 530 females and 160 males (AIHW 2024a).

Relationship to perpetrator

Among hospitalisations for FDV-related injuries in 2022–23, the most common perpetrator was parents (79% or about 235) among children aged 0–14, domestic partners (76% or about 610) for females aged 15–24 and other family members (54% or about 135) for males aged 15–24 (Figure 2; AIHW 2024a).

Figure 2: FDV-related hospitalisations for injuries due to abuse, by age group, sex and perpetrator of abuse, 2022–23

Figure 2 shows the number of males and females aged 0–14, 15–19 and 20–24 that were hospitalised for FDV-related injuries by relationship to perpetrator as well as the proportion of FDV-related injury hospitalisations in 2022–23.

Method of FDV-related injury

The most common methods of assault in hospitalisations for FDV-related injuries in 2022–23 were classified as:

- assault by bodily force (37% or about 110) or other maltreatment (35% or about 105) for people aged under 15 years

- assault by bodily force (55% or about 580) for people aged 15–24 years (AIHW 2024a).

The most common methods of assault were similar for males and females in both age groups (AIHW 2024a).

Principal injury diagnosis

The most common principal diagnosis in hospitalisations for FDV-related injuries in 2022–23 was injuries to the head for both children under 15 years (38% or about 115) and people aged 15–24 years (35% or about 375) (AIHW 2024a).

Among FDV-related injury hospitalisations in 2022–23:

- 1 in 21 (4.7% or 14) children under 15 years experienced brain injuries, while no brain injuries were recorded for people aged 15–24 years

- more than 1 in 5 (22% or about 235) people aged 15–24 years experienced injuries to limbs compared with 18% (or 52) for children under 15 years (AIHW 2024a).

Patterns of health service use

Using longitudinal, linked data from the National Health Data Hub, the AIHW explored how children and young people who have experienced FDV interact with the health care system, as well as their outcomes. The population studied included young people who had at least one FDV hospital stay (defined as an assault due to a family member or partner) from 2010–11 to 2020–21, while aged under 18 years.

The study found that:

- Young people who had an FDV hospital stay had around 10 (10.5) emergency department (ED) presentations per person, while a non-FDV related comparison group had just under 8 per person (7.9).

- About one in 2 (52%) young people who had multiple FDV hospital stays had 11 or more ED presentations.

- The leading cause of death among young people who had an FDV hospital stay was assault (27% of deaths) while the leading cause of death among a comparison group was suicide (19%) (AIHW 2024c).

See Health services for further discussion of FDSV-related hospitalisations.

Specialist homelessness services

Specialist homelessness services (SHS) can provide assistance to people who are experiencing homelessness, or who are at risk of homelessness, including clients who have experienced FDV.

Children experiencing FDV may seek SHS support with other family members, or independently. For children in particular, SHS support is critical to reduce the likelihood of a long-term experience of homelessness (Kaleveld et al. 2018).

In 2022–23, FDV was the main reason for seeking SHS assistance among 2 in 5 (40%) children aged 0–14 and around 1 in 6 (17%) young people aged 15–24 (AIHW 2024d).

-

1 in 2

specialist homelessness services clients aged 0-9 in 2022–23 had experienced family and domestic violence

Source: AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Collection

Irrespective of their main reason for seeking support, a large proportion of children and young people supported by SHS in 2022–23 had experienced FDV, with:

- over half (55%, or about 23,800 of 43,200) of children aged 0–9 years

- about half (48%, or about 8,300 of 17,400) of children aged 10–14 years

- about one-third (35% or about 18,200 of 52,300) of young people aged 15–24 years, with over three times as many females (about 13,800) as males (4,400) (AIHW 2023).

From 2011–12 to 2022–23, the proportion of clients assisted by SHS services who had experienced FDV has generally increased for children aged 0–9 years (from 42% to 55%) and 10–14 years (from 36% to 48%) and young people aged 15–24 years (from 29% to 35%) (AIHW 2024d).

In 2022–23, the majority (70%, or about 12,700) of young people aged 15–24 years who had experienced FDV presented to a SHS agency alone, with nearly 4 times as many females (10,000) as males (2,700). One in 10 (9.9% or about 3,200) children aged 0–14 years presented to a SHS agency alone (AIHW 2024d).

Housing outcomes

Fewer clients aged 0–14 and 15–24 years were homeless by the end of their support in 2022–23.

Many clients who are supported by SHS have achieved or progressed towards a more positive housing situation by the end of their support. Among SHS clients who have experienced FDV and whose ongoing SHS support ended in 2022–23:

- fewer clients were homeless at the end of support (about 4,600 clients aged 0–14 years and 4,000 clients aged 15–24 years) compared with their first period of support in 2022–23 (7,100 and 5,400, respectively)

- more clients were housed at the end of support (13,500 clients aged 0–14 years and 6,700 clients aged 15–24 years) compared with their first period of support in 2022–23 (10,900 and 5,600, respectively) (AIHW 2024d).

For information about all people who use SHS services and have experienced FDV, see Housing.

Impacts and outcomes of FDSV

Experiences of violence before the age of 15 are associated with many negative outcomes in adult life, including experiences of violence as an adult.

At the time of writing, the latest available data from the PSS (2016) showed that adults who had experienced violence before the age 15 years, when compared to those who had not, were:

- more likely to have lower levels of educational attainment, income and life satisfaction, and to report poor health

- twice as likely to experience any violence as an adult (71% compared with 33%)

- three times as likely to experience partner violence as an adult (28% compared with 8.9%)

- more likely to report a disability or long-term health condition at the time of the interview (46% compared with 29%) (ABS 2019a).

For a discussion among the general population, see Health outcomes and Behavioural outcomes.

Burden due to child abuse and neglect

The Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018 estimated the amount of burden that could be avoided if no one in Australia had experienced child abuse and neglect.

Burden due to child abuse and neglect estimates the mental health and injury outcomes experienced at all ages that are attributable to exposure during childhood. Three diseases were causally linked to child abuse and neglect: depressive disorders, anxiety disorders and suicide and self-inflicted injuries (AIHW 2021).

Child abuse and neglect was 1 of the top 3 leading contributors to total disease burden for females and males aged 0–14 years and 15–44 years in 2018.

Compared with other risk factors that contribute to total burden, in 2018, child abuse and neglect was:

- the 2nd leading risk factor for females and males aged 0–14

- the leading risk factor for females aged 15–44

- the 3rd leading risk factor for males aged 15–44 (AIHW 2021).

Females aged under 15 experienced 44% more burden from child abuse and neglect than males aged under 15 (AIHW 2021).

Overall, child abuse and neglect contributed to:

- about 810 deaths (0.5% of deaths)

- 2.2% of the total burden of disease and injury in Australia in 2018 (AIHW 2021).

Associations between child maltreatment and mental health disorders

The ACMS determined associations between child maltreatment and 4 mental health disorders identified using widely used and validated diagnostic instruments (Lawrence et al. 2023b). These disorders included lifetime major depressive disorder (MDD), current generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), current severe alcohol use disorder (SAUD) and current post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Childhood maltreatment was strongly associated with experiences of each mental health disorder. Among surveyed people who experienced child maltreatment:

- the proportion who had a mental disorder (48%) was over twice as high as people who had not experienced maltreatment (22%)

- 1 in 4 (25%) experienced lifetime MDD, about 1 in 6 (16%) current GAD, about 1 in 13 (7.8%) current PTSD and over 1 in 16 (6.1%) current SAUD

- the strongest association was with current PTSD, with people who experienced maltreatment about 5 times more likely than those who had not

- early and persistent negative effects on mental health were evident, with people at each of three age spans in life (16–24, 26–44 and 45 and over) about 3 times more likely to have a mental disorder than those who had not experienced child maltreatment (Haslam et al. 2023c; Scott et al. 2023).

Experiences of mental disorders were most strongly associated with experiences of emotional abuse, sexual abuse and multi-type maltreatment even after adjusting for the experience of other forms of child maltreatment (Haslam et al. 2023c).

These findings show that child maltreatment has both an early and lasting impact on people’s mental health throughout their lives. It is likely child maltreatment could have an even larger impact than currently shown as some types of mental disorders (for example, eating disorders and personality disorders) and symptoms that impaired an individual’s functioning but did not meet clinical thresholds were unable to be included in this study (Haslam et al. 2023c).

For more information about this study, see Children and young people: Measuring the extent of violence against children and young people and Data sources and technical notes.

Associations between child maltreatment and health risk behaviours

The ACMS determined associations between self-reported experiences of child maltreatment and six health risk behaviours: cannabis dependence, suicide attempts, non-suicidal self-injury, smoking, binge drinking and obesity (see Data sources and technical notes). People who had experienced child maltreatment were more likely than those who had not to report each health risk behaviour in the 12 months prior to the survey.

The strongest associations between experiences of child maltreatment and health risk behaviours were for:

- cannabis dependence at the time of the interview (6.2 times more likely), reported by 3.7% of those who had experienced child maltreatment

- suicide attempt in the past 12 months (4.6 times more likely), reported by 1.5% of those who had experienced child maltreatment

- self-harm in the past 12 months (3.9 times more likely), reported by 4.7% of those who had experienced child maltreatment (Haslam et al. 2023c).

The occurrence of these risk behaviours was higher among surveyed young people aged 16–24 who had experienced child maltreatment than other age groups, whereas binge drinking, recent cigarette smoking and obesity were more common in other age groups (Table 1).

Health risk behaviour | People aged 16–24 | People aged 25–44 | People aged 45 and over |

|---|---|---|---|

Current cannabis dependence | 5.9% | 3.7% | 1.4% |

Recent suicide attempt | 5.2% | 1.7% | 0.4% |

Recent self-harm | 14% | 5.6% | 1.5% |

Binge drinking | 8.8% | 13% | 13% |

Recent cigarette smoking | 20% | 25% | 18% |

Current obesity | 14% | 24% | 29% |

Notes:

- Current refers to at the time of the interview and recent refers to any occurrence in the past 12 months.

- Binge drinking refers to having six or more drinks for men or five or more drinks for women in a single session at least weekly over the past 12 months.

Source: Lawrence et al. 2023a, 2023b.

Child maltreatment was associated with an increased risk of all assessed health risk behaviours among young people aged 16–24 except binge drinking, which was common in both groups (8.8% for those with and 7.6% for those without experiences of child maltreatment) (Lawrence et al. 2023a).

Some health risk behaviours associated with child maltreatment were more common among either females or males aged 16–24 who had experienced maltreatment:

- more females reported self-harm (18% compared with 7.5% of males)

- more males reported current smoking (23% compared with 17% of females) and binge drinking (11% compared with 6.8%) (Lawrence et al. 2023a).

The increased likelihood of health risk behaviours among all age groups were found to be primarily driven by experiences of emotional abuse, sexual abuse and multi-type maltreatment as a child (Haslam et al. 2023c).

For more information about this study, see Children and young people: Measuring the extent of violence against children and young people and Data sources and technical notes.

Criminal justice involvement

Analysis of the ACMS data examining associations between child maltreatment and criminal justice involvement found that over 1 in 7 (15%) participants who experienced maltreatment reported ever being arrested. This compares with 8.1% of participants who reported no maltreatment and having ever being arrested (Mathews et al. 2023c).

The proportion of participants who experienced maltreatment and reported ever being arrested was higher for men (23%) and gender diverse participants (23%) compared with women (8.6%) (Mathews et al. 2023c).

Compared with non-maltreated participants, participants who experienced any maltreatment were:

- 2.3 times more likely to have ever been arrested

- 1.9 times more likely to have ever been convicted

- 1.4 times more likely to have ever been imprisoned (Mathews et al. 2023c).

There were statistically significant differences in arrest, conviction and imprisonment rates between male participants who reported and did not report maltreatment. For female participants, these differences were only statistically significant for arrest rates among those aged 25-44 (Mathews et al. 2023c).

There are stronger associations between child maltreatment and criminal justice involvement for those who experienced chronic multi-type maltreatment (that is, three or more types of maltreatment). One in 5 (20%) participants who experienced chronic multi-type maltreatment reported ever being arrested, compared with 10% of participants who reported no maltreatment or less than three types of maltreatment (Mathews et al. 2023c).

For more information about this study, see Children and young people: Measuring the extent of violence against children and young people and Data sources and technical notes.

Homicide

According to the National Homicide Monitoring Program (NHMP), in 2022–23 there were 16 people killed by a parent or parent-equivalent (filicide), with 3 females and 13 males. There were also 16 people killed by their child, with 7 females and 9 males (Miles and Bricknell 2024). Note that these data relate only to the relationship between people and does not indicate age.

-

About 3 in 5

victims of homicide and related offences aged under 18 years in 2022 were the victim of a family member or intimate partner

Source: ABS Recorded Crime - Victims

According to the ABS 2022 Recorded Crime – Victims data collection, among all recorded victims of homicide and related offences (including murder, attempted murder and manslaughter):

- about 3 in 5 (59%, or 37) of those aged under 18 years were the victim of a family member or intimate partner, with a similar number of females and males

- about 1 in 4 (27%, or 12) of those aged 18–24 years were the victim of a family member or intimate partner, with a similar number of females and males (ABS 2023f).

The rate of recorded FDV-related homicide and related offences among:

- victims aged under 18 years decreased from 0.7 to 0.4 per 100,000 from 2014 to 2020, and increased to 0.6 per 100,000 in 2022

- victims aged 18–24 has varied year to year (between 0.1 and 0.8 per 100,000), with 0.5 per 100,000 in 2022 (ABS 2023f).

Due to the low numbers of offences, any change year to year can result in a large proportional change in the victimisation rate.

Characteristics of filicide

Homicides in which a parent kills a child most commonly involve custodial mothers.

To analyse the characteristics of filicide (a parent killing a child) it is necessary to combine data from multiple years due to the relatively small number of incidents year to year. The latest available data from the NHMP for this purpose covers the period between 2000–01 and 2011–12. These data show that in Australia, there were about 240 incidents of filicide (a parent killing a child) involving about 285 victims:

- Almost all (96%, or about 275) of the victims were aged under 18; the remaining 4% (10) were aged 18–33.

- There were more male victims (56%, or about 160) than female victims (44%, or 125).

- The filicides were committed by 260 offenders (Brown et al. 2019).

The most common relationship between offender and victim was:

- custodial mother (46%, or about 135)

- custodial father (29%, or 82)

- stepfather (14%, or 41)

- non-custodial father (10%, or 27) (Brown et al. 2019).

A known history of domestic violence between the offender and an intimate partner was a characteristic in almost 1 in 3 (30%, or 57) filicide incidents (Brown et al. 2019).

Characteristics of FDV homicide types other than filicide

For all family and domestic homicide types other than filicide, most victims were aged over 25 years. Based on NHMP data between 2002–03 and 2011–12:

- about 1 in 4 (23% or 9) victims of homicides committed by a sibling were aged 15–24 years, with less aged 0–14 years (5.0% or 2)

- about 1 in 5 (20% or 18) victims of homicides committed by family members other than parents or siblings were aged 15–24, with a lower proportion of victims aged 0–14 years (7.6% or 7)

- about 1 in 7 (15% or 95) victims of intimate partner homicide were young people aged 15–24, with a lower proportion among people aged 0–14 years (0.2% or 1) (Cussen and Bryant 2015).

Noting that all family relationships include biological, adoptive and step relatives (Cussen and Bryant 2015).

Has it changed over time?

There are limited data on how the rate of experiences of FDSV among children and young people has changed over time. PSS data on the rate of experiences of sexual harassment and assault among women aged 18–24 in the 12 months prior to the survey (the 12-month prevalence rate) can be used to report on changes over time. Based on the latest available data, the 12-month prevalence rate of:

- sexual harassment was similar in 2021–22 (35%) and 2016 (38%) (ABS 2017b, 2023h)

- sexual assault increased from 2012 (2.2%*) to 2016 (4.5%) (ABS 2013, 2017b).

Note that estimates marked with an asterisk (*) should be used with caution as they have a relative standard error between 25% and 50%.

Is the experience of FDSV the same for everyone?

Some children and young people who share individual, socio-demographic and cultural characteristics may experience higher rates and/or different types of FDSV. However, there are limited data and research that investigates experiences of FDSV among children and young people in many population groups. Available national data show that:

- about 1 in 11 (9.4%) First Nations females and about 1 in 18 (5.5%) First Nations males aged 15–24 years in 2014–15 experienced physical family and domestic violence in the previous 12 months (ABS 2019b)

- a higher proportion of injury hospitalisations where a perpetrator was specified in 2022–23 were FDV-related for First Nations people compared with non-Indigenous people for those aged 0–14 (59% compared with 53%), 15–19 (73% compared with 35%), and 20–24 (64% compared with 22%) (AIHW 2024a)

- in 2016:

- nearly twice as many adults with disability (10%) as adults without disability (5.4%) had experiences of physical and/or sexual abuse before the age of 15 perpetrated by a parent/step-parent

- about 1 in 9 (12%) adults with disability had experiences of sexual abuse before the age of 15 compared with 1 in 17 (5.8%) adults without disability (AIHW 2022b).

For further discussions, see Population groups.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2013) 4906.0 – Personal Safety, Australia, 2012, ABS website, accessed 13 September 2023.

ABS (2017a) AIHW analysis of the Personal Safety Survey, 2016 TableBuilder, accessed 9 December 2022.

ABS (2017b) Personal Safety, Australia – 2016, ABS website, accessed 17 March 2023.

ABS (2019a) Characteristics and outcomes of childhood abuse, ABS website, accessed 17 March 2023.

ABS (2019b) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey, 2014–15, ABS website, accessed 17 March 2023.

ABS (2023a) Childhood abuse, ABS website, accessed 7 December 2023.

ABS (2023b) Partner violence, ABS website, accessed 7 December 2023.

ABS (2023c) Personal Safety, Australia, ABS website, accessed 3 May 2023.

ABS (2023d) Personal Safety, Australia methodology, ABS website, accessed 17 March 2023.

ABS (2023e) Recorded Crime – Victims, 2022, ABS website, accessed 5 July 2023.

ABS (2023f) Recorded Crime – Victims, 2022, customised request, ABS.

ABS (2023g) Recorded Crime – Victims methodology, ABS website, accessed 17 March 2023.

ABS (2023h) Sexual harassment, ABS website, accessed 13 September 2023.

ABS (2023i) Sexual violence, ABS website, accessed 13 September 2023.

AHRC (Australian Human Rights Commission) (2022) Time for respect: Fifth national survey on sexual harassment in Australian workplaces, AHRC, accessed 23 March 2023.

AIFS (Australian Institute of Family Studies) (2015) Risk and protective factors for child abuse and neglect, AIFS website, accessed 17 March 2023.

AIFS (2017) Risk and protective factors for child abuse and neglect, AIFS website, accessed 17 March 2023.

AIFS (2018) What is child abuse and neglect?, AIFS website, accessed 17 March 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2021) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on risk factor burden, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 17 March 2023.

AIHW (2022a) Family, domestic and sexual violence data in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 17 April 2023.

AIHW (2022b) People with disability in Australia–Violence against people with disability, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 16 March 2023.

AIHW (2023) Specialist homelessness services collection annual report 2022-23, AIHW website, accessed 13 February 2024.

AIHW (2024a) AIHW analysis of the National Hospital Morbidity Database.

AIHW (2024b) Child protection Australia 2022–23, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 18 July 2024.

AIHW (2024c) Health service use among young people hospitalised due to family and domestic violence, 2010–11 to 2020–21, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 23 August 2024.

AIHW (2024d) Specialist Homelessness Services Collection data cubes 2011–12 to 2022–23, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 13 February 2024.

Blue Knot Foundation (2021) 20/21 Annual report, Blue Knot Foundation, accessed 19 October 2022.

Boxall H, Pooley K and Lawler S (2021) Do violent teens become violent adults? Links between juvenile and adult domestic and family violence, AIC (Australian Institute of Criminology), accessed 17 March 2023.

Bravehearts (2021) Annual report 20/21, Bravehearts, accessed 17 March 2023.

Brown T, Bricknell S, Bryant W, Lyneham S, Tyson D and Fernandez Arias P (2019) Filicide offenders, AIC, accessed 17 March 2023.

Campo M (2015) Children’s exposure to domestic and family violence – Key issues and responses, AIFS, accessed 17 March 2023.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) (2022) Violence prevention, CDC website, accessed 17 March 2023.

Coumarelos C, Weeks N, Bernstein S, Roberts N, Honey N, Minter K, & Carlisle E (2023) Attitudes matter: The 2021 National Community Attitudes towards Violence against Women Survey (NCAS), Findings for Australia, ANROWS (Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety), accessed 19 April 2023.

Cussen T and Bryant W (2015) Domestic/family homicide in Australia, Research in practice no. 38, AIC, accessed 17 March 2023.

C3P (Canadian Centre for Child Protection) (2017) Survivors’ survey full report 2017, C3P Inc., accessed 17 March 2023.

DPMC (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet) (2021) National Strategy to Prevent and Respond to Child Sexual Abuse, DPMC, Commonwealth of Australia, accessed 25 July 2022.

Dragiewicz C, O’Leary M, Ackerman J, Foo E, Bond C, Young A and Reid A (2020) Children and technology-facilitated abuse in domestic and family violence situations: Full report, Office of the eSafety Commissioner, Australian Government, accessed 17 March 2023.

DSS (Department of Social Services) (2022) National plan to end violence against women and children 2022–2032, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 17 March 2023.

eSafety Commissioner (2022) Sending nudes and sexting, eSafety Commissioner website, accessed 13 March 2023.

Fazel S, Smith EN, Chang Z and Geddes JR (2018) 'Risk factors for interpersonal violence: an umbrella review of meta-analyses', The British Journal of Psychiatry, 213(4):609–614, doi:10.1192/bjp.2018.145.

Fitz-gibbon K, Meyer S, Boxall H, Maher J and Roberts S (2022) Adolescent family violence in Australia: A national study of service and support needs for young people who use family violence, ANROWS, accessed 17 March 2023.

Haslam DM, Lawrence D, Mathews B, Higgins DJ, Hunt A, Scott JG, Dunne MP, Erskine HE, Thomas HJ, Finkelhor D, Pacella R, Meinck F and Malacova E (2023a) 'The Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS), a national survey of the prevalence of child maltreatment and its correlates: methodology', Medical Journal of Australia, 218 (6 Suppl): S5-S12, doi:10.5694/mja2.51869.

Haslam DM, Malacova E, Higgins D, Meinck F, Mathews B, Thomas H, Finkelhor D, Havighurst S, Pacella R, Erskine H, Scott JG and Lawrence D (2023b) 'The prevalence of corporal punishment in Australia: Findings from a nationally representative survey', Australian Journal of Social Issues, doi: 10.1002/ajs4.301.

Haslam D, Mathews B, Pacella R, Scott JG, Finkelhor D, Higgins DJ, Meinck F, Erskine HE, Thomas HJ, Lawrence D and Malacova E (2023c) The prevalence and impact of child maltreatment in Australia: Findings from the Australian Child Maltreatment Study: Brief Report, Australian Child Maltreatment Study, Queensland University of Technology, accessed 21 April 2023.

Havighurst SS, Mathews B, Doyle FL, Haslam DM, Andriessen K, Cubillo C, Dawe S, Hawes DJ, Leung C, Mazzucchelli TG, Morawska A, Whittle S, Chainey C and Higgins DJ (2023) Corporal punishment of children in Australia: The evidence-based case for legislative reform, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 47(3):100044, doi: 10.1016/j.anzjph.2023.100044

Heywood W, Myers P, Powell A, Meikle G and Nguyen D (2022) National Student Safety Survey: report on the prevalence of sexual harassment and sexual assault among university students in 2021, Social Research Centre website, accessed 27 April 2023.

Higgins DJ, Mathews B, Pacella R, Scott JG, Finkelhor D, Meinck F, Erskine HE, Thomas HJ, Lawrence DM, Haslam DM, Malacova E and Dunne MP (2023) 'The prevalence and nature of multi-type child maltreatment in Australia', Medical Journal of Australia, 218 Suppl 6:S19–S25, doi:10.5694/mja2.51868.

Humphreys C and Healey L (2017) PAThways and research into collaborative inter-agency practice: collaborative work across the child protection and specialist domestic and family violence interface: The PATRICIA project – Final report, ANROWS, accessed 1 March 2023.

Jones C, Woodlock D and Salter M (2021) Evaluation of PartnerSpeak, University of New South Wales, accessed 17 March 2023.

Katz E, Nikupeteri A and Laitinen M (2020) 'When coercive control continues to harm children: Post separation fathering, stalking and domestic violence', Child Abuse Review, 29(4):310–324, doi:10.1002/car.2611.