Antenatal care

The National Perinatal Data Collection defines antenatal care as a planned visit between a pregnant woman and a midwife or doctor to assess and improve the wellbeing of the mother and baby throughout pregnancy. Antenatal care is associated with positive maternal and child health outcomes – the likelihood of receiving effective health interventions is increased through attending antenatal care. It does not include visits where the sole purpose is to confirm the pregnancy (AIHW 2023).

For more information on antenatal care, see Antenatal care in Australia's mothers and babies.

During 2020, there were rapid changes to the way antenatal care was delivered in Australia – with the purpose of reducing the spread of COVID-19 – through the introduction of telehealth (Woods et al. 2023).

Reports on the changes to antenatal care provision have been mixed. A 2020 Australian study found that changes to antenatal care provision did not affect maternal mental health but may have increased overall neonatal morbidity (Woods et al. 2023). Whereas a 2020 survey of Australian midwives and pregnant women reported positive effects from the introduction of telehealth due to the pandemic, with convenience and increased accessibility for women who lived in remote settings or had caregiving responsibilities (Kluwgant et al. 2022).

The type of antenatal care visit (face-to-face or telehealth) is not available in the National Perinatal Data Collection (NPDC). Therefore, data presented for Telehealth services is from the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS). Future data linkage between the NPDC and MBS would allow this to be explored in more depth.

Data presented for Duration of pregnancy at first antenatal care visit and Number of antenatal care visits are from the NPDC.

Telehealth services

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Australian Government expanded telehealth items to the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) in March 2020, including antenatal care items. These temporary items included antenatal attendances and services provided by video-conference or telephone, which became permanent from 1 January 2022. Note that the MBS items used for analysis in this report may not capture all items that health providers use when providing antenatal care.

Overall, telehealth-integrated antenatal care can be a viable alternative to in-person consultations without compromising pregnancy outcomes (Atkinson et al. 2023; Thirugnanasundralingam et al. 2023). However, uncertainty remains around whether telehealth during the pandemic led to underdiagnosis of maternal conditions such as gestational diabetes and hypertension (Abelman et al. 2023; Thirugnanasundralingam et al. 2023).

In a recent survey of Australian midwives and pregnant women, respondents stated that they positively valued the integration of telehealth services into their maternity care (Kluwgant et al. 2022).

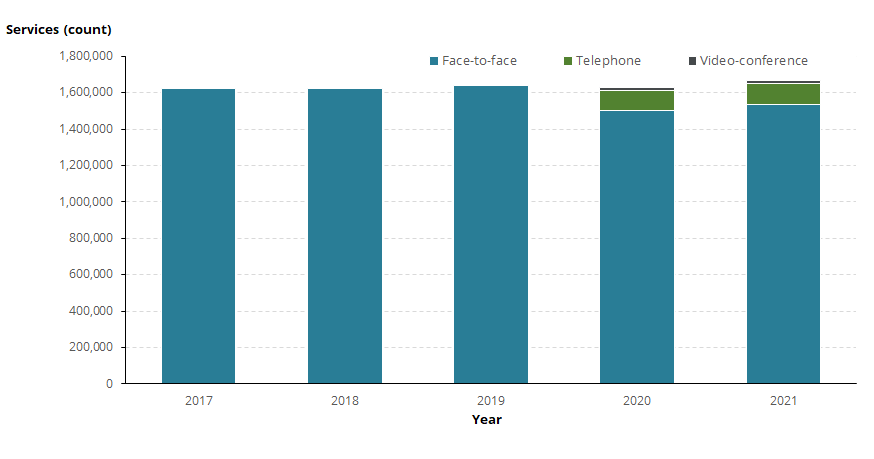

Figure 4 presents MBS data on the types of antenatal care services in Australia.

Figure 4: Number of MBS antenatal care services in Australia, by type of service, 2017 to 2021

Notes:

- Face-to-face (antenatal care) services includes MBS items 16400, 16500, 16590, 16591, 82100, 82105 and 82110.

- Telehealth (antenatal care) services delivered by video-conference includes MBS items 91211, 91212, 91850 and 91853. These items were added to the MBS on 13 March 2020, therefore no data is available prior to this date.

- Telehealth (antenatal care) services delivered by telephone includes MBS items 91218, 91219, 91855 and 91858. These items were added to the MBS on 13 March 2020, therefore no data is available prior to this date.

- State/Territory is determined according to the address (at time of claiming) of the individual to whom the service was rendered.

- The MBS is a billing scheme and the data are subject to provider’s clinical judgment and billing discretion. This means that services may not be billed with 100% accuracy, and they could also be billed outside of the MBS.

- Due to the nature of the MBS, the use of general time-tiered items, and lack of antenatal subspeciality items for some professions, not all services will be clearly represented. For example, currently there are no specific telehealth antenatal items available for Nurse Practitioners to claim. As such, any antenatal services provided by Nurse Practitioners would be claimed under broader telehealth items available.

Source: AIHW analysis of Medicare Benefits Schedule item reports on the Services Australia website on 15 February 2024.

Overall, there were a similar number of antenatal services provided between 2017 and 2020 (ranging from 1.62 million to 1.64 million) and a higher number of services delivered in 2021 (1.67 million).

Between 2017 and 2019, face-to-face delivery was the only type of antenatal care available, with over 1.6 million services provided each year.

In 2020 – after the introduction of MBS telephone and videoconference antenatal care services – face-to-face visits decreased to below 1.5 million visits, or 92% of antenatal care services. Telephone and video-conference accounted for 6.8% and 1.0% of antenatal care services, respectively.

In 2021, face-to-face visits increased to above 1.5 million visits. The type of antenatal care service was mostly face-to-face (92%), followed by telephone (7.1%) and video-conference (0.9%) antenatal care services.

Figure 5 presents data on the type of antenatal care services for states and territories.

Figure 5: Proportion of antenatal care services, by type of service and state or territory of usual residence, 2020 and 2021

Bar chart shows proportion of type of antenatal care delivery between 2020 and 2021.

In 2020, all jurisdictions used a mixed type of antenatal care service delivery ranging from 88% to 98% for face-to-face, 2.0% to 10.3% for telephone and 0.2% to 1.9% for video-conference. This was true regardless of the degree to which outbreaks and lockdowns were occurring. However, Victoria experienced the greatest shift to telehealth, which coincided with the nation’s most widespread and sustained lockdowns.

In 2021, there was an increase in face-to-face antenatal service delivery across jurisdictions (ranging from 89% to 98%) and a corresponding decrease in telephone and video-conference antenatal care service delivery (ranging from 1.6% to 9.3% and 0.1% to 1.4%, respectively).

Duration of pregnancy at first antenatal visit

The Australian Pregnancy Care Guidelines (Department of Health and Aged Care 2020) recommend that a woman has her first antenatal visit within the first 10 weeks of pregnancy.

The proportion of women receiving antenatal care in the first trimester (before 14 weeks’ gestational age) is a widely reported indicator of antenatal care. Regular antenatal care in the first trimester is associated with better maternal health in pregnancy, fewer interventions in late pregnancy and positive child health outcomes (AIHW 2023).

Figure 6 presents data on duration of pregnancy at first antenatal visit.

Figure 6: Proportion of women who gave birth, by duration of pregnancy at first antenatal visit and state and territory of birth, 2015 to 2021

Line graph shows duration of pregnancy at first antenatal visits by state and territory of birth between 2015 and 2021.

Between 2015 and 2019, the proportion of women who had at least one antenatal visit in the first trimester increased across Australia, from 64.6% in 2015 to 76.6% in 2019. Modelling showed that this was an annual increase of 3.0 percentage points. The observed proportion of women who had at least one antenatal visit in the first trimester was 79.1% in 2020 and 79.6% in 2021, which was similar to the predicted proportions based on the modelling (80.0% in 2020 and 83.0% in 2021).

Data for modelling exclude 'Not stated' data and therefore may not match the proportions presented in the data visualisation above. For more information on modelling the trend over time, see Methods.

Women who lived in some geographical locations were more likely to have at least one antenatal visit in the first trimester. Explore the map below (Figure 7) to view data on the number and proportion of women who had at least one antenatal visit in the first trimester by PHN, remoteness and SA3.

Figure 7: Proportion of women who gave birth and had at least one antenatal visit in the first trimester, by selected geography, 2017 to 2021

Line graph shows primiparous and multiparous women by number of antenatal visits by state and territory of birth between 2016 and 2021.

Number of antenatal visits

Ongoing antenatal visits are required for specific activities as pregnancy progresses, including assessing fetal growth, testing for pregnancy-related conditions, and preparing for labour and birth (Department of Health and Aged Care 2020).

For first-time mothers (primiparous), at least 10 antenatal visits are recommended during pregnancy, for mothers who have previously given birth (multiparous) and for subsequent uncomplicated pregnancies, 7 visits are recommended (Department of Health and Aged Care 2020).

Figure 8 presents data on number of antenatal visits. Data exclude Victoria for data quality reasons. This may have an impact on the results in this section, as Victoria was significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic relative to most Australian jurisdictions.

Figure 8: Proportion of primiparous and multiparous women who gave birth, by whether they met the Australian Pregnancy Care Guidelines and state and territory of birth, 2015 to 2021

Line graph shows primiparous and multiparous women by number of antenatal visits by state and territory of birth between 2015 and 2021.

Between 2015 and 2019, the proportion of first-time mothers who had 10 or more antenatal visits decreased (from 63.3% in 2015 to 61.8% in 2019) (data exclude Victoria). Modelling showed that this was an annual decrease of 0.4 percentage points. The observed proportion of first-time mothers who had 10 or more antenatal visits was 59.1% in 2020 and 59.3% in 2021, which was lower than the predicted proportions based on the modelling (61.9% in 2020 and 61.5% in 2021). This equated to around 4,670 fewer first-time mothers attending the recommended 10 or more antenatal visits than predicted in 2020 and 2021 combined.

In 2020 and 2021, despite the increase in the proportion of first-time mothers who had less than 10 antenatal care visits, there was no increase in the proportion of babies with adverse outcomes among first-time mothers such as pre-term birth, low birthweight, Apgar score of less than 7 or admission to SCN or NICU, compared with previous years.

Between 2015 and 2019, the proportion of mothers who had previously given birth and who had 7 or more antenatal visits decreased (from 85.9% in 2015 to 85.2% in 2019) (data exclude Victoria). Modelling showed that this was an annual decrease of 0.2 percentage points. The observed proportion of mothers who had previously given birth and who had 7 or more antenatal visits was 83.6% in 2020 and 84.8% in 2021, which was similar to the predicted proportions based on the modelling (84.8% in 2020 and 84.5% in 2021).

Data for modelling exclude 'Not stated' data and therefore may not match the proportions presented in the data visualisation above. For more information on modelling the trend over time, see Methods.

Women who lived in some geographical locations were more likely to have 5 or more antenatal visits. Explore the map below (Figure 9) to view data on the number and proportion of women who had 5 or more antenatal visits by PHN, remoteness and SA3.

Figure 9: Proportion of women who gave birth and had 5 or more antenatal visits, by selected geography, 2017 to 2021

Map shows proportion of women who had 5 or more antenatal visits by selected geographies and years.

Abelman SH, Svetec S, Fekder L and Boelig RC (2023) ‘Impact of telehealth implementation on diagnosis of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy’, Am J Obstet Gynecol, 5(8):101043, doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2023.101043.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2023) Australia’s mothers and babies, AIHW, Australian Government.

Atkinson J, Hastie R, Walker S, Lindquist A and Tong S (2023) ‘Telehealth in antenatal care: recent insights and advances’, BMC Med, 21(332):2023, doi:10.1186/s12916-023-03042-y.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2020) Clinical practice guidelines: pregnancy care, Department of Health and Aged Care wesbite, Australian Government.

Kluwgant D, Homer C and Dahlen H (2022) ‘Never let a good crisis go to waste: Positives from disrupted maternity care in Australia during COVID-19’, Midwifery, 110(2022):103340.

Thirugnanasundralingam K, Davies-Tuck M, Rolnik DL, Reddy M, Mol BW, Hodges R and Palmer KR (2023) ‘Effect of telehealth-integrated antenatal care on pregnancy outcomes in Australia: an interrupted time-series analysis’, The Lancet: Digital Health, 5(11):798-811.

Woods A, Ballard E, Kumar S, Mackle T, Callaway L, Kothari A, De Jersey S, Bennett E, Foxcroft K, Willis M, Amoako A and Lehner C (2023) ‘The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on antenatal care provision and associated mental health, obstetric and neonatal outcomes’, Journal of Perinatal Medicine, doi:10.1515/jpm-2023-0196.