Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Female clients experiencing family and domestic violence and persistent homelessness in 2020–21

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2024) Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Female clients experiencing family and domestic violence and persistent homelessness in 2020–21, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 30 October 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2024). Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Female clients experiencing family and domestic violence and persistent homelessness in 2020–21. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/shs-females-experiencing-fdsv-persistent-homeless

MLA

Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Female clients experiencing family and domestic violence and persistent homelessness in 2020–21. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 29 October 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/shs-females-experiencing-fdsv-persistent-homeless

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Female clients experiencing family and domestic violence and persistent homelessness in 2020–21 [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024 [cited 2024 Oct. 30]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/shs-females-experiencing-fdsv-persistent-homeless

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2024, Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Female clients experiencing family and domestic violence and persistent homelessness in 2020–21, viewed 30 October 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/shs-females-experiencing-fdsv-persistent-homeless

This article is part of Specialist homelessness services client pathways: analysis insights

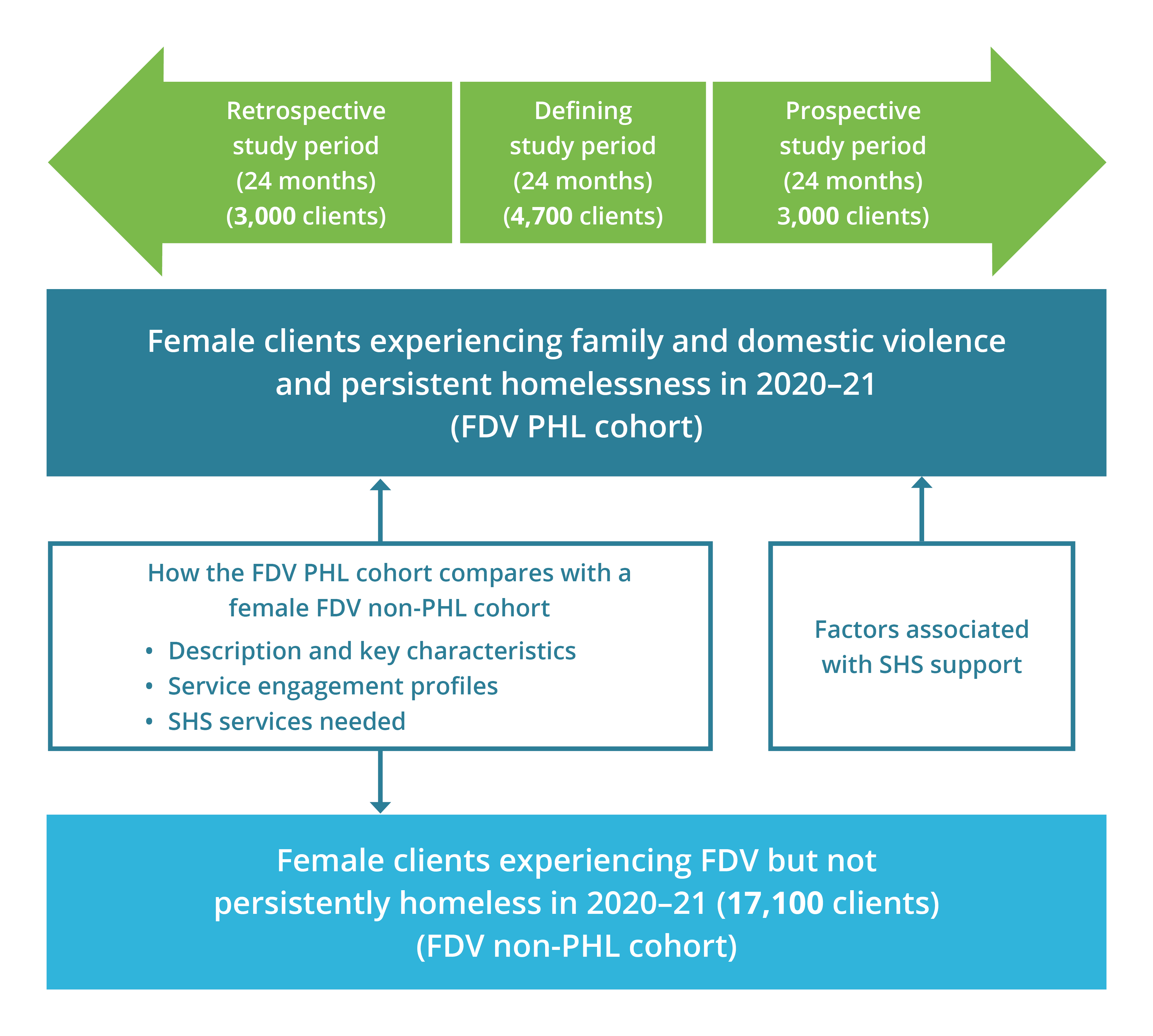

Each study cohort examines the characteristics and experiences of a group of specialist homelessness services (SHS) clients and provides valuable insights into the support profile of vulnerable client groups over time.

Each web article draws on SHSC data from 2011–12 onwards, national as well as state or territory breakdowns have been provided where possible.

Children and young people

- Specialist homelessness services and income support among young people

- Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Children on care and protection orders in 2014–17

- Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Young clients aged 18 to 24 in 2018–20

- Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Young clients aged under 18 in 2011–13

- Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Young clients presenting alone in 2015–16

Client vulnerabilities

- Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Clients exiting custodial arrangements in 2014–17

- Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Clients with mental health issues in 2015–16

- Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Clients with problematic drug or alcohol use in 2015–16

Indigenous Australians

Specialist homelessness services clients

Family, domestic and sexual violence

- Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Female clients experiencing family and domestic violence and persistent homelessness in 2020–21 (this page)

- Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Female clients experiencing family and domestic violence and returning to homelessness in 2020–21

- Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Female clients with family and domestic violence experience in 2015–16