Hospitalisations for chronic kidney disease

Page highlights:

Chronic kidney disease hospitalisations as a principal or additional diagnosis

- In 2020–21, approximately 2 million hospitalisations (17%) involved chronic kidney disease.

Variation between population groups

- In 2020–21, there were around 30,800 hospitalisations for chronic kidney disease among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – around 3,500 hospitalisations per 100,000 population.

Trends for chronic kidney disease as a principal diagnosis

- Hospitalisations for chronic kidney disease as a principal diagnosis more than doubled between 2000–01 and 2020–21, from 24,200 to 58,200 hospitalisations.

Data presented in this section are based on single episodes of care, including multiple hospitalisations experienced by the same individual. Because people receiving dialysis are admitted for this purpose multiple times a week, hospitalisations involving dialysis as the principal diagnosis are not included in analyses of CKD hospitalisations, unless otherwise stated.

For more information, see Hospitalisations for dialysis.

In 2020–21, approximately 2 million hospitalisations (17% of all hospitalisations in Australia) recorded chronic kidney disease (CKD) (including dialysis) as a principal and/or additional diagnosis.

Dialysis accounted for 80% of CKD hospitalisations in 2020–21. After excluding all hospitalisations where dialysis was recorded as the principal diagnosis, CKD hospitalisations accounted for 3.3% of all hospitalisations in Australia in 2020–21.

In 2020–21:

- there were around 58,200 hospitalisations with CKD as a principal diagnosis – the diagnosis largely responsible for hospitalisation

- there were around 333,000 hospitalisations with CKD as an additional diagnosis – a coexisting condition with the principal diagnosis or a condition arising during hospitalisation that affects patient management

- on average, people hospitalised with a principal diagnosis of CKD (excluding dialysis as a principal diagnosis) stayed 2.8 days in hospital. For people who required hospitalisation for one night or more, the average length of stay was 4.8 days.

Chronic kidney disease is a broad term that includes multiple conditions that affect kidney function, any of which might be recorded as the principal diagnosis causing hospitalisation. The most commonly recorded principal diagnosis for CKD in 2020–21 was ‘chronic kidney disease’, followed by ‘kidney tubulo-interstitial diseases’ (Table 1).

Table 1: Major causes of hospitalisation for chronic kidney disease (as the principal diagnosis), 2020–21

| Major cause of hospitalisation | Number |

|---|---|

| Chronic kidney disease | 22,244 |

| Kidney tubulo-interstitial diseases | 15,251 |

| Glomerular diseases | 5,550 |

| Other disorders of kidney and ureter | 3,921 |

| Complications related to dialysis and transplant | 2,588 |

| Hypertensive kidney disease | 1,525 |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 1,235 |

| Congenital malformations | 1,200 |

| Unspecified kidney failure | 320 |

| Dialysis (excluding preparatory care) | 1,613,405 |

| Haemodialysis | 1,606,824 |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 6,581 |

| Preparatory care for dialysis | 4,318 |

| Total | 1,671,557 |

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Chronic kidney disease hospitalisations as a principal or additional diagnosis

When CKD affects patient care during hospitalisation – but is not the principal diagnosis – it is recorded as an additional diagnosis. Except where dialysis is the principal diagnosis, CKD is more often coded as an additional diagnosis.

The leading principal diagnoses in 2020–21 when CKD was listed as an additional diagnosis were:

- heart failure: 20,600 hospitalisations (6.2%)

- type 2 diabetes: 12,100 hospitalisations (3.6%)

- sepsis (blood poisoning): 11,500 hospitalisations (3.5%)

- acute kidney failure: 10,600 hospitalisations (3.2%)

- acute myocardial infarction (heart attack): 7,200 hospitalisations (2.2%).

CKD is often comorbid with cardiovascular disease and diabetes. In 2020–21, cardiovascular diseases (also known as circulatory diseases) were the most common type of principal diagnosis when CKD was an additional diagnosis, accounting for 18% (60,600) of these hospitalisations. Endocrine diseases, including type 1 and type 2 diabetes, accounted for 8.1% of hospitalisations where CKD was an additional diagnosis.

Injuries were also common principal diagnoses when CKD was an additional diagnosis (10.8% or 35,900 of these hospitalisations). Of these, complications associated with cardiac and vascular prosthetic devices, implants and grafts (6,200 hospitalisations) and fractures of the femur (5,300 hospitalisations) were the most common reasons for hospitalisation (Table 2).

CKD is associated with an increased risk of fractures, due to disturbances in mineral and bone metabolism as a result of the disease (Moe et al. 2006). Progression or development of kidney disease is also a risk associated with surgery, due to an increase in creatinine following surgery (Ishani et al. 2011).

Table 2: Leading principal diagnoses when chronic kidney disease was an additional diagnosis, by ICD-10-AM chapter and code, 2020–21

| ICD-10-AM chapter | Hospitalisations | Percentage of hospitalisations where CKD was an additional diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 60,646 | 18.2 |

| Heart failure (I50) | 20,648 | 6.2 |

| Acute myocardial infarction (heart attack) (I21) | 7,245 | 2.2 |

| Cerebral infarction (ischemic stroke) (I63) | 4,147 | 1.2 |

| Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes | 35,902 | 10.8 |

| Complications of cardiac and vascular prosthetic devices, implants and grafts (T82) | 6,197 | 1.9 |

| Fracture of femur (S72) | 5,327 | 1.6 |

| Complications of procedures, not elsewhere classified (T81) | 1,808 | 0.5 |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | 28,439 | 8.5 |

| Acute kidney failure (N17) | 10,631 | 3.2 |

| Other disorders of the urinary system (N39) | 7,583 | 2.3 |

| Obstructive and reflux uropathy (N13) | 2,943 | 0.9 |

| Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | 26,819 | 8.1 |

| Type 2 diabetes (E11) | 12,074 | 3.6 |

| Other disorders of fluid, electrolyte and acid-base balance (E87) | 8,256 | 2.5 |

| Type 1 diabetes (E10) | 2,658 | 0.8 |

| Diseases of the digestive system | 22,885 | 6.9 |

| Other diseases of the digestive system (K92) | 2,937 | 0.9 |

| Gallstones (K80) | 1,982 | 0.6 |

| Paralytic ileus and intestinal obstruction without hernia (K56) | 1,710 | 0.5 |

Note: Excludes chronic kidney disease as a principal diagnosis and diagnoses of ‘Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified’.

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Variation by age and sex

In 2020–21, the number of CKD hospitalisations increased with age, with 70% occurring in those aged 65 and over. CKD hospitalisation rates (as a principal or additional diagnosis, excluding dialysis as a principal diagnosis):

- were between 1.2 and 2.0 times higher for females than males before the age of 45. From age 45, rates were higher for men than women

- were highest in those aged 85 and over for both males and females (19,000 and 11,200 per 100,000 population, respectively) – 1.8 and 1.7 times as high as males and females aged 75–84 (10,800 and 6,600 per 100,000, respectively) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Chronic kidney disease hospitalisation rates, by diagnosis type, age and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows the rates of hospitalisation for chronic kidney disease by age groups and sex, with rates of hospitalisation increasing with age for males and females with people aged 85 and over having the highest rates (1.7 times higher than people aged 75 to 84 for principal and/or additional diagnoses of CKD).

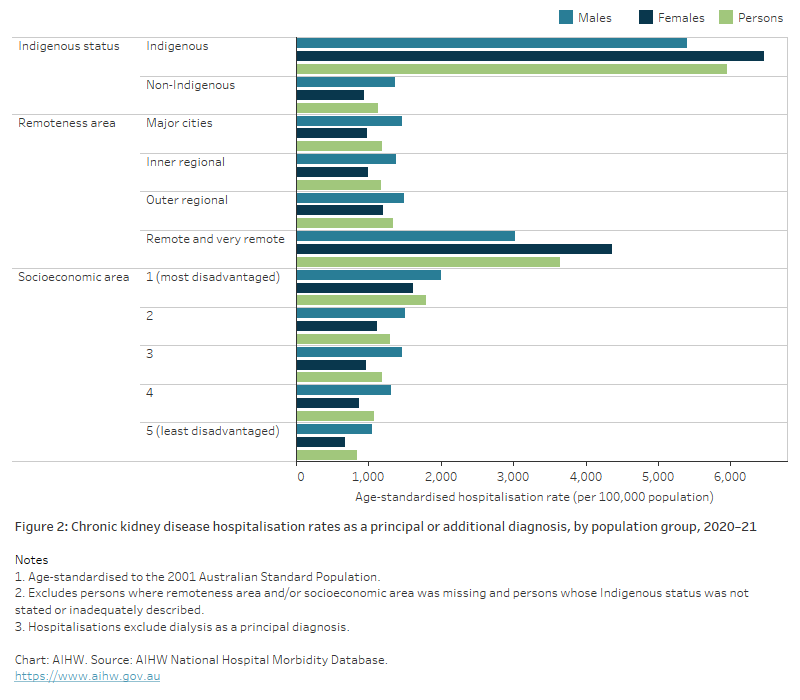

Variation between population groups

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2020–21, there were around 30,800 hospitalisations for CKD as a principal or additional diagnosis among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – around 3,500 hospitalisations per 100,000 population.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations:

- The hospitalisation rate among Indigenous Australians was 5.3 times as high as the rate among non-Indigenous Australians.

- The hospitalisation rate among Indigenous females was 6.9 times as high as the rate among non-Indigenous females, while the rate among Indigenous males was 4.0 times as high as the rate among non-Indigenous males (Figure 2).

Remoteness and socioeconomic area

In 2020–21, CKD hospitalisation rates (as the principal or additional diagnosis, excluding dialysis as a principal diagnosis) increased with remoteness and socioeconomic disadvantage.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the population groups, CKD hospitalisation rates were:

- 3.1 times as high for people living in Remote and very remote areas as for people living in Major cities

- 4.5 times as high among females living in Remote and very remote areas as for females living in Major cities

- 2.1 times as high among males living in Remote and very remote areas as for males living in Major cities

- 2.1 times as high for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with those living in the highest socioeconomic areas

- 2.4 times as high among females living in the lowest socioeconomic areas as for females living in the highest socioeconomic areas

- 1.9 times as high among males living in the lowest socioeconomic areas as for males living in the highest socioeconomic areas (Figure 2).

See Geographical variation in disease: diabetes, cardiovascular and chronic kidney disease for more information on CKD hospitalisations by state/territory, Population Health Network and Population Health Area.

Figure 2: Chronic kidney disease hospitalisation rates as a principal or additional diagnosis, by population group, 2020–21

The bar chart shows rates of hospitalisation for chronic kidney disease by sex based on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status, remoteness area and socioeconomic area. Indigenous people had rates of hospitalisation for CKD 5.3 times higher than non-Indigenous people. Hospitalisation rates for CKD across remoteness areas were similar for all areas except Remote and very remote regions, where people were hospitalised for CKD at rates 3.1 times as high as those living in Major cities. People living in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas were hospitalised at higher rates than all other areas, with rates decreasing with increasing socioeconomic advantage in the area which people lived. Males were hospitalised at higher rates than females across all measures except for Indigenous females and females living in Remote and very remote areas.

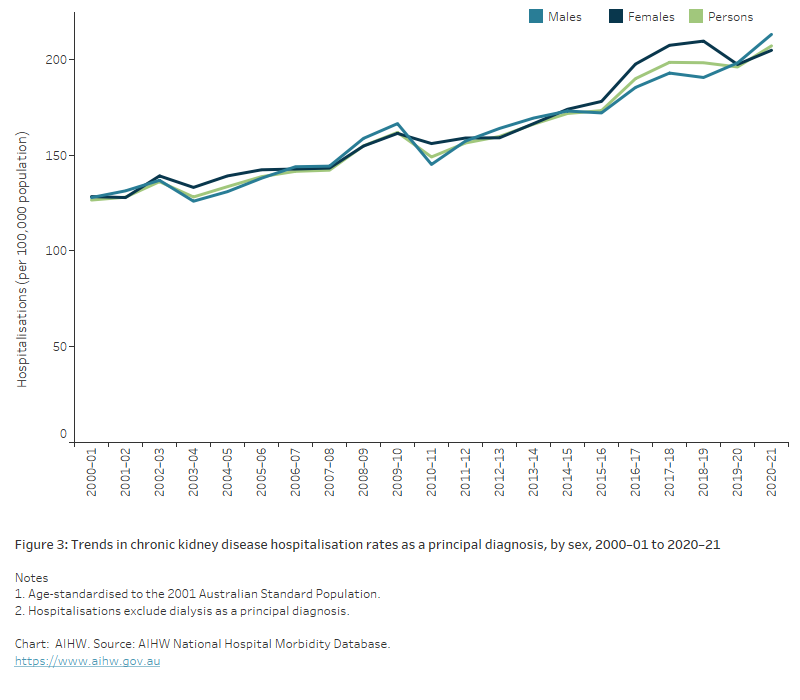

Trends for chronic kidney disease as a principal diagnosis

The number of hospitalisations for CKD as a principal diagnosis (excluding dialysis as a principal diagnosis) more than doubled between 2000–01 and 2020–21, from 24,200 to 58,200 hospitalisations. Over this period, the age-standardised rate rose by 64% (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Trends in chronic kidney disease hospitalisation rates by diagnosis type and sex, 2000–01 to 2020–21

The line chart shows an increasing trend in age-standardised CKD hospitalisation rates between 2000-01 to 2020–21, when CKD was a principal diagnosis and a principal or additional diagnosis. Over this time, when CKD was a principal diagnosis, hospitalisations increased by 64%.

Supplementary chronic condition codes

CKD (stages 3 to 5) can be recorded in hospitalisation data as a supplementary code, as opposed to a principal or additional diagnosis. Supplementary codes represent a selection of clinically important chronic conditions that are part of the patient’s current health status on admission which do not meet criteria for inclusion as additional diagnoses but may affect clinical care.

- CKD (stages 3 to 5) was the ninth most-assigned supplementary code for hospitalisations in 2020–21, assigned in 1.8% of hospital admissions.

- Since the supplementary code for CKD was introduced in 2015–16, the number of hospitalisations recording CKD as an additional diagnosis has fallen.

ANZDATA (Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry) (2021) ANZDATA 44th Annual Report 2021, ANZDATA website, accessed 30 June 2022.

Ishani A, Nelson D, Clothier B, Schult T, Nugent S, Greer N et al. (2011) The magnitude of acute serum creatinine increase after cardiac surgery and the risk of chronic kidney disease, progression of kidney disease, and death, Archives of Internal Medicine, 171(3):226–233, doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.514.

KHA (Kidney Health Australia) (2016a) An introduction to haemodialysis, KHA, Melbourne, accessed 22 February 2022.

KHA (2016b) An introduction to peritoneal dialysis, KHA, Melbourne, accessed 22 February 2022.

Moe S, Drüeke T, Cunningham J, Goodman W, Martin K, Olgaard K et al. (2006) ‘Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO), Kidney International, 69:1945–1953, doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5000414.