Hospitalisations for dialysis

Page highlights

In 2020–21, 1.6 million (14%) of hospitalisations in Australia were for dialysis.

The number of hospitalisations for dialysis nearly tripled between 2000–01 and 2020–21, from 582,000 to 1.6 million.

In 2020–21, there were 264,000 hospitalisations for dialysis (as the principal diagnosis) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, 30,300 per 100,000 population.

Dialysis is the most common reason for hospitalisation in Australia, accounting for 14% of all hospitalisations in 2020–21 (1.6 million hospitalisations). Although the majority of people admitted to hospital for dialysis receive haemodialysis, a small number receive peritoneal dialysis. Data on this web page includes hospitalisations for both types of dialysis.

Hospitalisation data count the number of dialysis episodes rather than the number of people who receive dialysis. Most people undergoing dialysis attend 3 sessions per week (ANZDATA 2021).

For more information about people receiving dialysis, see Dialysis.

What is dialysis?

Dialysis is an artificial way to remove waste and excess water from the blood, and regulate safe levels of circulating agents (such as potassium, calcium and phosphorous) in the body, a function usually performed by the kidneys. It is most often provided to treat chronic kidney failure, but is sometimes needed in cases of acute kidney failure, where the kidneys have been temporarily damaged due to illness or injury.

There are 2 types of dialysis: peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis.

Peritoneal dialysis is an internal filtration process requiring the placement of a catheter (a thin, flexible plastic tube) into the abdomen, which remains in place as long as dialysis is required. Peritoneal dialysis uses the peritoneal membrane inside the abdominal cavity to filter the blood inside the body.

The process involves filling the abdomen with a sterile dialysis solution, called dialysate. Over 4–8 hours, waste is drawn out of the blood through the peritoneal membrane and into the dialysate. The used solution is then drained out of the body and replaced with a new solution. This process is called an exchange and takes around 30–45 minutes.

Between exchanges, the person is free to continue their usual activities. Peritoneal dialysis can be performed either by the person 3 or 4 times during the day (continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis) or automatically by a machine at night for about 8–10 hours while the person sleeps (automated peritoneal dialysis).

As the necessary equipment is portable, peritoneal dialysis can be performed almost anywhere. Individuals do not need to be in a hospital or clinic and can usually manage the procedure without assistance.

Haemodialysis is an external filtration process where the blood is diverted from the body to a machine which removes waste and excess fluid. It involves an initial procedure to join an artery and vein together with either a fistula or graft, that serves as the access point to the dialysis machine (dialyser). Once this access point is ready, haemodialysis sessions take place for an average of 4 to 5 hours 3 times per week (ANZDATA 2021). Once the blood has been filtered by the dialyser, it is returned to the body through the access point.

Haemodialysis can be done at home or in specialised dialysis centres located either in hospitals or satellite units. The process involves specialised plumbing installation for the dialyser and the person requires assistance to be connected to the machine. If performed at home, the procedure may be done more frequently for shorter periods or overnight.

Sources: KHA 2016a, 2016b.

Variation by age and sex

In 2020–21, hospitalisation rates for dialysis as the principal diagnosis:

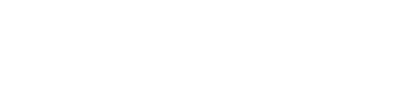

- were 1.6 times higher in males than in females. Age-specific rates for males were higher than those for females across all age groups

- increased with age up to ages 75–84, with 76% of hospitalisations occurring in people aged 55 and over. Dialysis hospitalisation rates for males and females were highest among those aged 75–84 (39,000 and 19,200 per 100,000 population, respectively) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Dialysis hospitalisation rates, as a principal diagnosis, by age and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows hospitalisations for dialysis by age and sex in 2020–21, which people aged 75-84 having the highest rates of hospitalisation. Prior to age 75, hospitalisations rates increase with age, and then decrease after age 85. The pattern was the same for males and females, with males having higher rates than females.

Trends over time

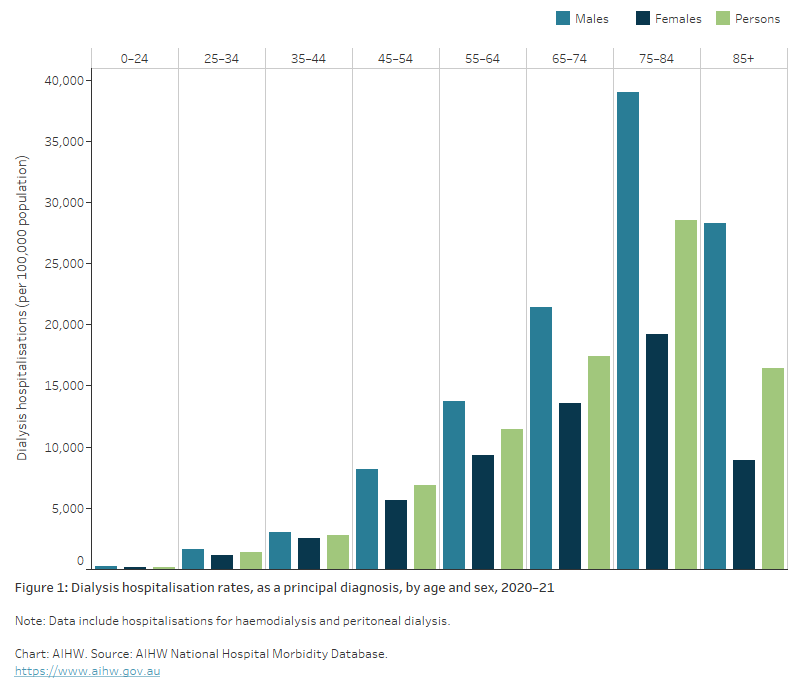

The number of hospitalisations for dialysis rose by 177% between 2000–01 and 2020–21, from 582,000 to over 1.6 million. After adjusting for changes in the age structure of the population over this time, this equated to an increase of 76% in the rate of dialysis hospitalisations. Note that this does not capture trends in dialysis performed outside of hospitals.

The rate of hospitalisations for dialysis among males was consistently higher than for females over the period, with both showing similar respective rates of increase (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Trends in dialysis hospitalisation rates, as a principal diagnosis, by sex, 2000–01 to 2020–21

The line chart shows the age-standardised trend in hospitalisations for dialysis from 2000-01 to 2020–21, by sex. Between 2000-01 and 2020–21, hospitalisations for dialysis increased by 76%. Males had higher rates of dialysis than females across this period.

Variation between population groups

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

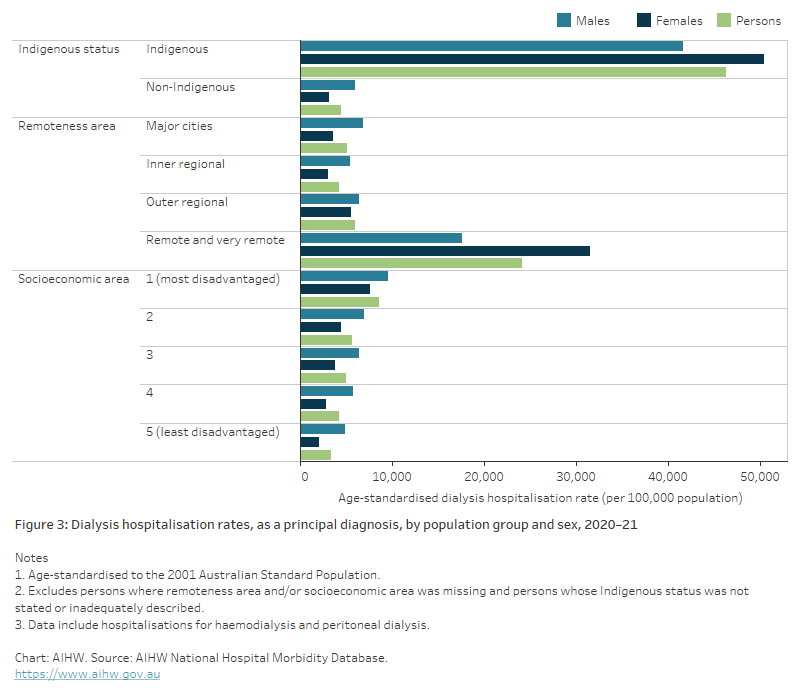

In 2020–21, there were 264,000 hospitalisations for dialysis (as the principal diagnosis) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (113,000 males, 151,000 females).

Indigenous Australians were hospitalised for dialysis at a rate of 30,300 per 100,000 population. Indigenous females were hospitalised for dialysis at a rate of 34,600 per 100,000 population, and Indigenous males at a rate of 26,000 per 100,000 population.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of these populations:

- Indigenous Australians were hospitalised for dialysis at a rate over 10 times as high as that for non-Indigenous Australians

- Indigenous females were hospitalised for dialysis at a rate that was 16 times as high as that for non-Indigenous females. Indigenous males were hospitalised at a rate 7.0 times as high as that for non-Indigenous males (Figure 3).

Remoteness and socioeconomic area

In 2020–21, hospitalisation rates for dialysis (as the principal diagnosis) varied by remoteness and socioeconomic area (Figure 3).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the population groups:

- dialysis hospitalisation rates were 4.7 times as high in Remote and very remote areas as in Major cities

- females living in Remote and very remote areas were hospitalised for dialysis at a rate 8.8 times as high as that for females living in Major cities. Males living in Remote and very remote areas were hospitalised for dialysis at a rate that was 2.6 times the rate of males living in Major cities

- hospitalisations for dialysis were 2.5 times as high for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas as for those living in the highest

- females living in the lowest socioeconomic areas were hospitalised at a rate 3.7 times as high as that for females living in the highest socioeconomic areas. Males living in the lowest socioeconomic areas were hospitalised at a rate 2.0 times as high as that for males living in the highest socioeconomic areas.

See Geographical variation in disease: diabetes, cardiovascular and chronic kidney disease for more information on dialysis hospitalisations by state/territory, Population Health Network and Population Health Area.

Figure 3: Dialysis hospitalisation rates, as a principal diagnosis, by population group and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows rates of hospitalisation for dialysis by sex based on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status, remoteness area and socioeconomic area. Indigenous people had rates of hospitalisation for dialysis 10.4 times higher than non-Indigenous people. Hospitalisation rates for dialysis across remoteness areas were similar for all areas except Remote and very remote regions, where people were hospitalised for dialysis at rates 4.7 times as high as those living in Major cities. Hospitalisations for dialysis increased gradually by socioeconomic area, with people living in the least disadvantaged socioeconomic areas having the lowest rates of hospitalisation for dialysis, and those living in the most disadvantaged areas having the highest. Males were hospitalised at higher rates than females across all measures except for Indigenous females and females living in Remote and very remote areas.

Further information

For more information on hospitalisation for dialysis for Indigenous people, see: Profiles of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with kidney disease

Reference

ANZDATA (Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry) (2021) ANZDATA 44th Annual Report 2021, ANZDATA website, accessed 30 June 2022.