Intercountry adoption in Australia

Intercountry adoption refers to the adoption of children from countries other than Australia through one of Australia’s official adoption programs. These children are legally able to be placed for adoption, but generally have had no previous contact or relationship with their adoptive parent(s). A simplified overview of the intercountry adoptions process in Australia is presented in Figure 1.

Note: Intercountry adoptions may be finalised in various ways, depending on the type of adoption. Processes might vary between jurisdictions.

Source: AIHW

Changes in overseas domestic adoption practices, and social factors such as the degree of acceptance of single motherhood or falling fertility rates in countries of origin, can affect the number and characteristics of children for whom intercountry adoption is considered appropriate. As traditional countries of origin improve in areas of economic and social development, options for domestic care also improve, and fewer children need intercountry adoption. This can result in more stringent eligibility criteria or further program restrictions for adopting young children, and an increasing proportion of those in need of intercountry adoption being children with complex backgrounds, health issues or impairments.

Directly influenced by the countries with which Australia has an adoption program, the majority of intercountry adoptions in Australia have consistently been from Asian countries of origin. Variations in the intercountry programs, including restrictions on these programs by either Australian authorities or authorities in the country of origin, contribute to changes in intercountry adoption trends.

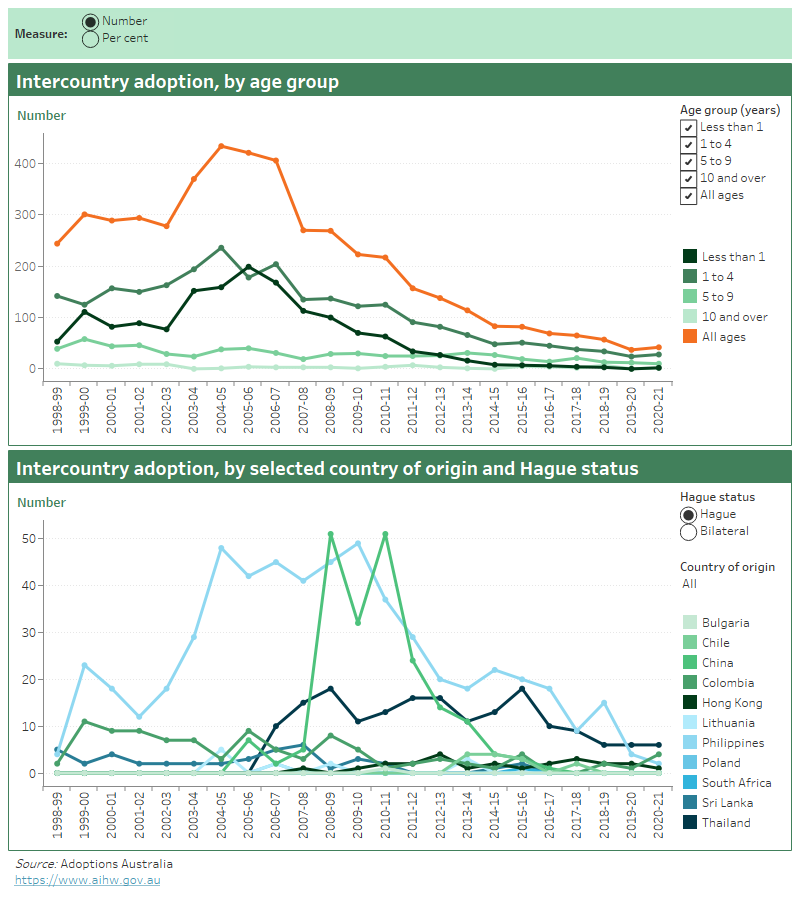

Two panels presented. The top panel shows the number of intercountry adoptions per year, by age group of the adoptees, from 1998-99 to 2020-21. Adoptees aged 1 to 4 have been the most numerous group in all but one of the years across this period. Adoptees under 12 months were similarly numerous up to 2011-12, but have since represented a minor proportion. The bottom panel shows the number of intercountry adoptees, by year and by country of origin, from 1998-99 to 2020-21. For Hague adoptions, the Philippines has been the main country of origin for most of this period. For bilateral adoptions the main country of origin has varied over this period, but 2013-14 has been either South Korea or Taiwan.

Types of intercountry adoption programs

Australia has been a party to the Hague Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption (the Hague Convention) since December 1998. The Hague Convention establishes:

- uniform standards and procedures between countries, including legally binding standards and safeguards;

- a system of supervision to ensure set standards and procedures are observed;

- channels of communication between authorities in countries of origin and countries of destination for children being adopted; and,

- principles that focus on the need for intercountry adoptions to occur only where it is in the best interest of the child with respect to their fundamental rights, and to prevent abduction, sale, or traffic of children.

Not all of the countries with which Australia has an adoption program are parties to the Hague Convention. However, programs are established only where Australia can be satisfied that the principles of the Hague Convention are being met, regardless of whether the country is a signatory. In this context, bilateral arrangements exist with South Korea and Taiwan, which have not currently ratified the Hague Convention.

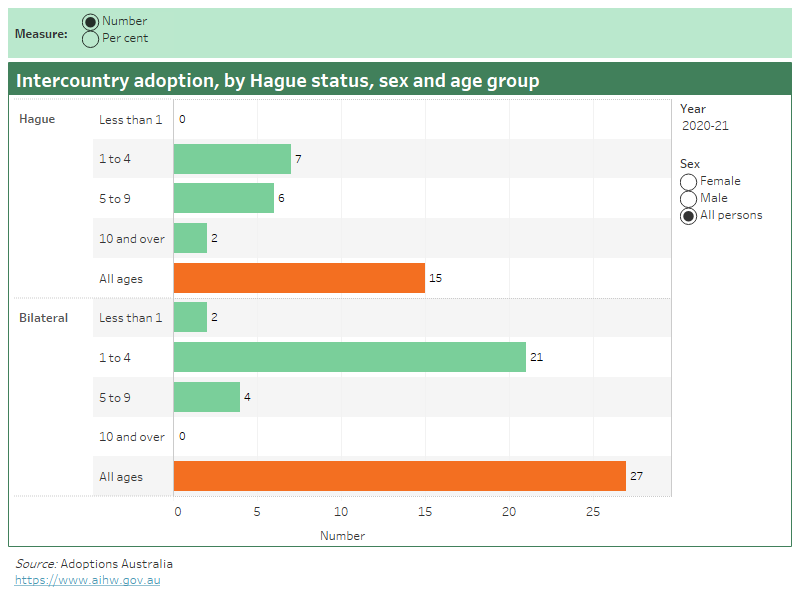

The plot shows the age distribution of intercountry adoptees, by year, Hague status (Hague or bilateral), and sex of the child. For both Hague and bilateral adoptions finalised in 2020-21, most adoptees were aged 1 to 4 at the time of placement for both males and females.

Processing times

Several factors outside of the control of Australian authorities can affect processing times, including the number and characteristics of children in need of intercountry adoption, the number of applications received, and the resources of the overseas authority. For example, Australia’s partner countries generally have more applications from prospective adoptive parents willing to parent healthy younger children and infants than there are such children in need of adoption.

In contrast, a growing proportion of children in need of intercountry adoption are considered to have special needs and more complex care requirements. Targeted programs in countries of origin can assist with matching eligible prospective adoptive parents with these children and potentially reduce processing times.

It is also possible that some Australian applicants have their application in a country for a number of years with no outcome, and may change their application to an adoption program in another country of origin before they are successfully matched with a child.

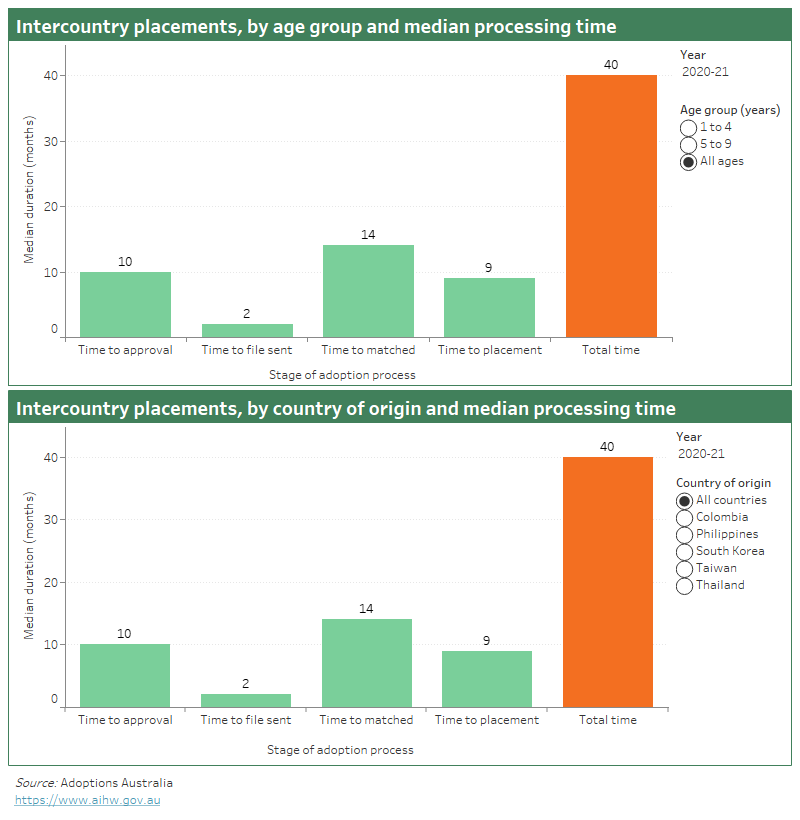

Two panels presented. Both show the average processing times of intercountry adoptees, by year of adoption order finalisation, split by the stage of the process. In the top panel, this is presented by age group of adoptee. For adoptions finalised in 2020-21, the overall process took longer on average for children aged 5 to 9 compared with those aged 1 to 4. In the bottom panel, average duration is presented by country of origin. The overall process took longest on average for children from the Philippines (66 months), where the period from when the file was sent overseas to when the child was matched was the longest stage (40 months, on average).

Adoption of children with special needs

Special needs in the Australian adoptions context is defined as the level of resources or support services required by the adoptee and/or their adoptive family to foster healthy development and wellbeing, and to support positive family functioning and prevent adoption disruption. Special needs is examined through a continuum of level of need that is broken down into the following categories: no additional care needs, minor additional care needs, and moderate to substantial additional care needs. Children are assessed at the time they are matched and again 12 months after they were placed.

Children with special needs represent a growing proportion of children for whom intercountry adoptions is deemed appropriate, and the adoption process can be more difficult due to the need to find families who can care for the child’s specific needs.

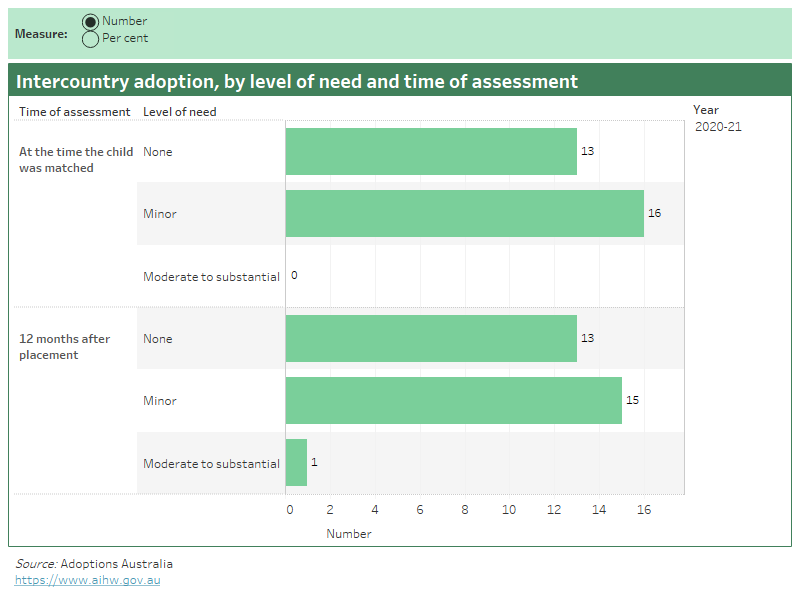

The plot shows the level of need for intercountry adoptees, by year, and by the time at which they were assessed (at the time the child was matched, and 12 months after placement). Of the children who entered Australia in 2019-20, 13 were assessed to have no additional care needs, 16 assessed to have minor additional care needs, and 0 assessed as having moderate to substantial care needs. When re-assessed 12 months after placement, one fewer child was assessed as having minor additional care needs, and one more child was assessed as having moderate to substantial care needs.

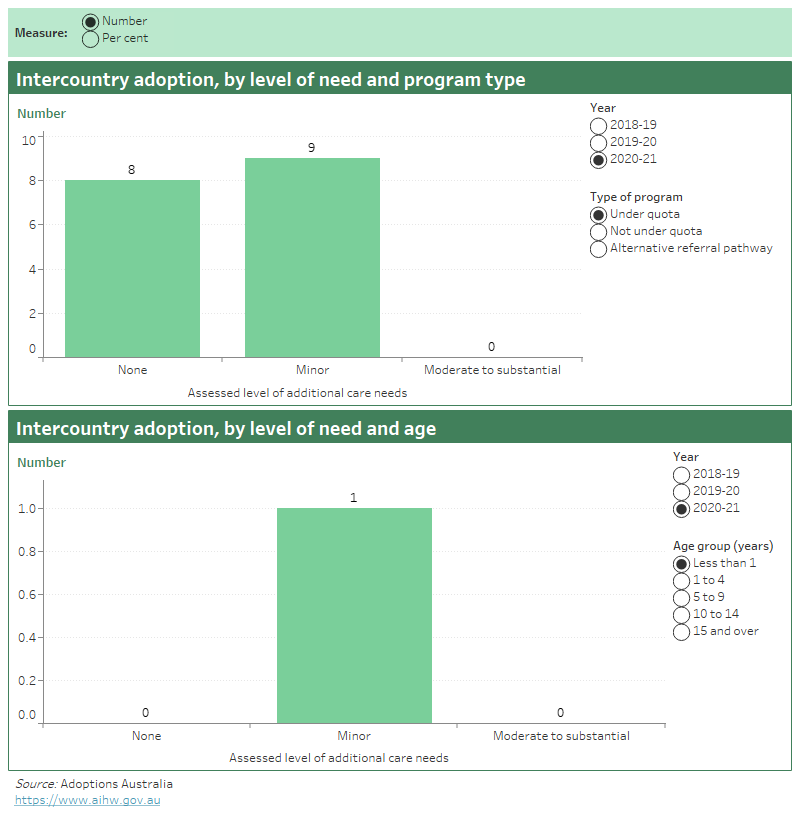

Two panels presented, both of which present data on the level of need of intercountry adoptees, assessed 12 months after they entered Australia. The top panel presents this data by the type of program through which the child placement occurred. For intercountry adoptees who entered Australia in 2019–20 under quota programs, the number assessed as having no additional care needs (8) was similar to those assessed as having minor additional care needs (9), with none assessed as having moderate to substantial additional care needs. The bottom panel presents data on assessed level of need by age group of the adoptee. For intercountry adoptees who entered Australia in 2019–20, the vast majority of those with no or minor additional care needs are aged 1 to 4.

Explanatory notes

Age is calculated from date of birth, in completed years. For intercountry adoptions, it is the age at which the child was placed with the adoptive family.

Only countries of origin with which Australia had an active adoption program since 2011–12 are presented. As at June 2021, Australia had an active intercountry adoption program with 13 countries: Bulgaria, Chile, China, Colombia, Hong Kong, India, Latvia, Poland, South Africa, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan and Thailand.

Since 1998, adoptions where the Hague Convention had not entered into force in the adoptive child’s country of origin before the file of the prospective parent(s) was sent were referred to as ‘non-Hague’ adoptions for national reporting purposes. Commencing 2017–18, the term ‘bilateral’ is used to refer to such adoptions.

The median length of time calculated for intercountry adoption processing times is reported in whole months. Medians are not presented where there were fewer than 3 placements in an age group or from a country of origin.