Older Australians living in rural and remote communities

This feature article reports on the health and wellbeing of older people (aged 65 and over) living in rural and remote areas, which encompass many diverse locations and communities. The geographical isolation of some rural and remote communities can impact the experience of ageing due to the availability of services, transport, infrastructure, employment opportunities, housing and living arrangements, and community resources (AIHW 2019b; Davis and Bartlett 2008).

Throughout this feature article, ‘older people’ refers to people aged 65 and over. Where this definition does not apply, the age group in focus will be specified. The 'Older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people' feature article defines older people as aged 50 and over. This definition does not apply to this feature article, with Indigenous Australians aged 50–64 not included in the information presented unless specified.

Regions of Australia

The regions within Australia can be broadly divided into Major cities, Inner regional, Outer regional, Remote and Very remote. These areas are based on the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia, which takes into consideration the road distances people have to travel for services (ABS 2020d). The majority of Australia’s total population lives in Major cities (72%), with a further 26% in Inner regional and Outer regional and 1.9% in Remote and Very remote areas (AIHW 2020a).

The term ‘rural and remote’ covers the areas outside Australia’s Major cities. Due to small population sizes, data for Outer regional, Remote and Very remote are sometimes combined for reporting.

Demographic profile

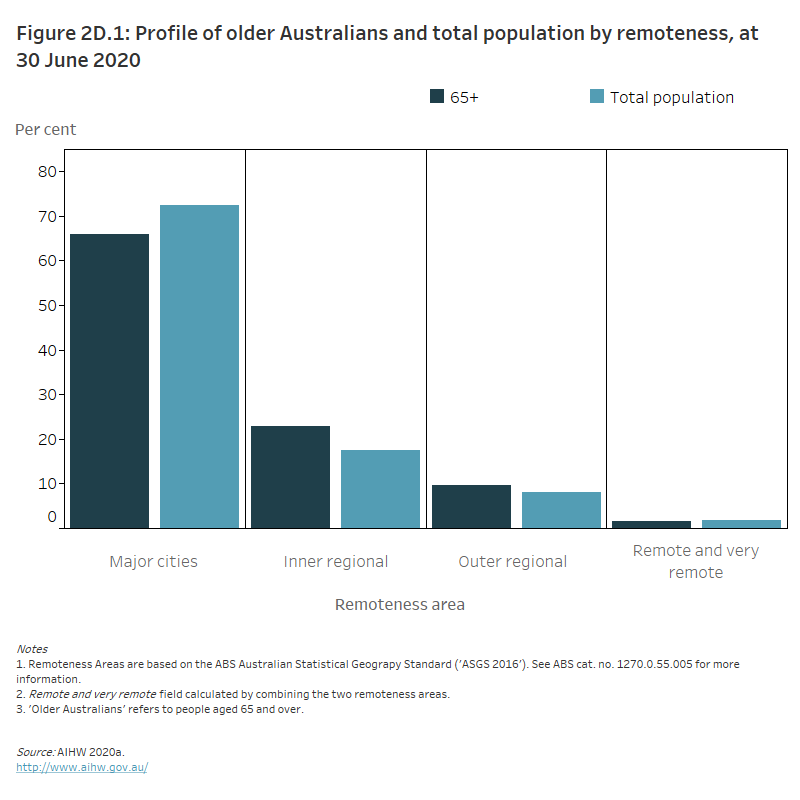

At 30 June 2020, there were an estimated 4.1 million older people (aged 65 and over) living in Australia. Two-thirds lived in Major cities (66%, 2.7 million), nearly 1 in 4 in Inner regional areas (23%, 0.9 million) and the remaining 11% lived in Outer regional and Remote and very remote areas combined (0.5 million, Figure 2D.1). Compared with the total Australian population, a higher proportion of older people lived in Inner regional areas and a lower proportion in Major cities. Nearly 3 in 4 (72%) of the total Australian population lived in Major cities, 18% in Inner regional areas and the remaining 9.9% lived in Outer regional and Remote and very remote areas combined (AIHW 2020a) (Figure 2D.1).

Younger people are more likely to live in, and migrate to, Major cities because of education and job opportunities, and to easily access social activities. However, older people may also move to Major cities for better access to services (Davis and Bartlett 2008).

Figure 2D.1: Profile of older Australians and total population by remoteness, at 30 June 2020

The column graph shows that a higher proportion of older Australians live in Inner regional and Outer regional areas in comparison to the total population (66% of older Australians live in Major cities, 23% in Inner regional areas, 9.7% in Outer regional areas and 1.5% in Remote and very remote areas).

Health

Rural and remote areas tend to overlap with areas identified as the most disadvantaged in Australia (ABS 2018a). Australians living in rural and remote areas, on average, have shorter lives, higher death rates, higher levels of disease and injury, and poorer health outcomes compared with people living in metropolitan areas (AIHW 2019b, 2020b). This can be linked to multiple factors including lifestyle risk factors, socioeconomic disadvantages and poorer access to health services (NRHA 2011).

The health disadvantages of communities in rural and remote Australia can also be impacted by the availability of health care services. Accessibility issues, such as access to dental, general practitioner and community services, and higher prevalence of health risk factors, such as higher rates of smoking, disability and physical inactivity, can all contribute to poorer health outcomes (NRHA 2011).

For more information, see Rural & remote health.

Chronic conditions

In Australia, chronic conditions and diseases are the leading cause of ill health, disability and death, having a significant impact on the health sector in all regions. Although the prevalence of many health conditions does not vary between people living in areas of increasing remoteness, some conditions are reported more frequently among people living outside of Major cities. These include mental and behavioural conditions, arthritis, back pain and asthma (AIHW 2019b). Alongside the factors identified above, differences in the rates of these chronic conditions may contribute to the poorer health outcomes of Australians living in rural and remote communities.

Similar patterns in health conditions and remoteness are observed among older Australians (aged 65 and over) specifically. For example, compared with older people living in Major cities, older people living in rural and remote areas have a higher prevalence of chronic conditions such as arthritis, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ABS 2018c). Although differences exist in these specific conditions, no differences were detected between remoteness categories in the presence of multiple chronic conditions more generally in 2017–18: around 1 in 2 older people reported having 2 or more chronic conditions in Major cities (50%), Inner regional (51%) and Outer regional, remote and very remote areas (50%). In comparison, around 1 in 6 (17%) older people in Inner regional areas, and around 1 in 5 in Major cities (21%) and Outer regional, remote and very remote areas (23%), reported having no chronic conditions (ABS 2018c).

The differing sociodemographic profiles of urban and remote communities also likely explain some of the divergence in health conditions and outcomes between these regions. For instance, there are differences in age composition and other demographic characteristics associated with health and wellbeing. At 30 June 2020, around 1 in 10 (9%) people living in Very remote areas were aged 65 and over, compared with 1 in 7 (15%) in Major cities. Moreover, at 30 June 2016, around 1 in 5 (22%) older people living in Very remote areas were Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people, compared with only 0.5% in Major cities (ABS 2018b). Indigenous Australians tend to develop chronic conditions earlier in life and are more likely to have higher rates of hospitalisations and poorer health outcomes than non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2019b).

For more information on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health by remoteness, see Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework (HPF) report and Older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Disability

The prevalence of disability among older Australians has remained stable over recent years. Based on data from the 2018 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC), 1 in 2 (50%) older people had disability in 2018. This was similar in 2015 (51%) and 2012 (53%) (ABS 2019a; AIHW analysis of ABS 2019c). Even though the proportion of older people with disability has been stable, the number of older people with disability has increased:

- 1.94 million in 2018

- 1.80 million in 2015

- 1.72 million in 2012 (AIHW analysis of ABS 2013, 2016, 2019c).

Of these older Australians with disability, 1 in 3 (34%) lived in rural and remote areas (AIHW analysis of ABS 2019c). Overall, the prevalence of disability among older Australians did not vary systematically by level of remoteness, with a slightly lower prevalence of older Australians with disability in Major cities (49%) and Outer regional areas (49%), and a slightly higher prevalence in Inner regional (52%) and Remote areas (55%) (AIHW analysis of ABS 2019c). However, looking solely at those older Australians with disability who report mild limitations in core activities, a step-wise relationship between prevalence of disability and level of remoteness was observed: lowest in Major cities (19%), followed by Inner regional (21%), Outer regional (22%) and Remote (27%) areas. This relationship does not extend to those older Australians with disability who report other levels of limitation in core activities; for example, moderate limitations were most prevalent in Inner regional areas (8.7%), whereas severe limitations were most prevalent in Remote areas (9.1%).

Deaths

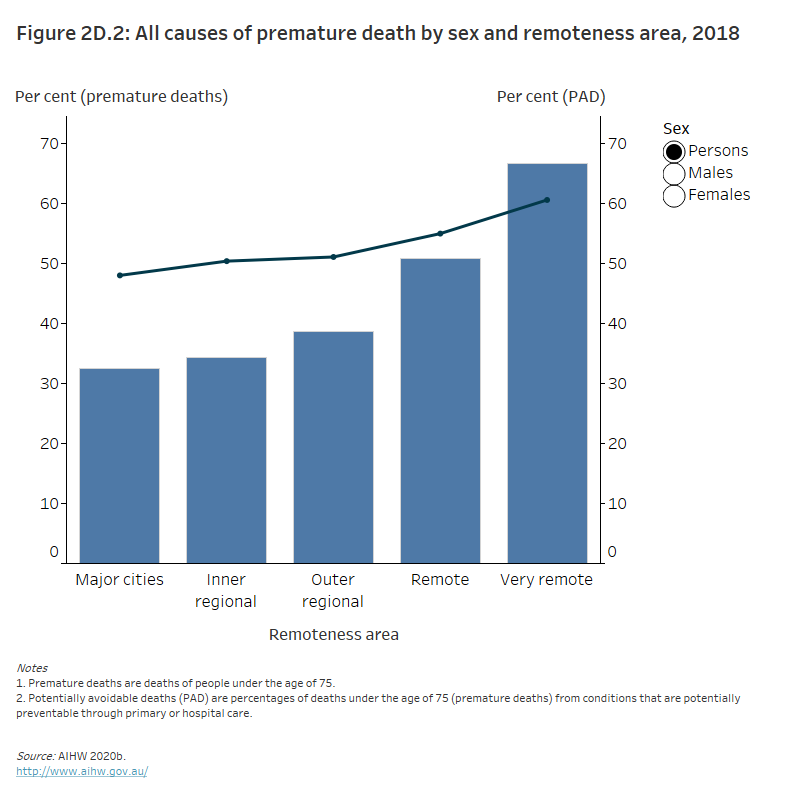

People living in rural and remote areas are more likely to die at a younger age than their counterparts living in Major cities among both men and women. They have higher mortality rates and higher rates of potentially avoidable deaths – deaths under the age of 75 from conditions that are potentially preventable through primary or hospital care – than those living in Major cities (Figure 2D.2).

Across Australia in 2018, the median age at death decreased as remoteness increased for both sexes and the overall population. Men had the lowest median age at death across the remoteness areas: 68 years in Very remote areas compared with 79 years in Major cities (Table 2D.1). Of the total number of deaths that occurred in Very remote areas in 2018, 2 in 3 (67%) were premature deaths – people aged under 75. Around 3 in 5 (61%) of these premature deaths were considered to be potentially avoidable. In contrast, 33% of all deaths were premature deaths in Major cities, of which nearly half (48%) were considered potentially avoidable (AIHW 2020c) (Figure 2D.2). As discussed in ‘Chronic conditions’ below, the differences between remoteness areas may be due to the characteristics of the population.

Figure 2D.2: All causes of premature death by sex and remoteness area, 2018

The column and line graph shows that the proportion of people who died prematurely and the proportion of potentially avoidable premature deaths in Australians aged under 75 increased with increasing remoteness. The proportion of premature deaths was highest among males in very remote areas (71% of men died prematurely with 61% of these premature deaths being potentially avoidable).

|

Sex |

Major cities |

Inner regional |

Outer regional |

Remote |

Very remote |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Men |

79 |

78 |

76 |

73 |

68 |

|

Women |

85 |

84 |

83 |

80 |

70 |

|

People |

82 |

81 |

79 |

76 |

69 |

Source: AIHW 2020c.

Burden of disease

The impact of disease, injury and dying early can be measured as the burden of disease on a population. A summary measure of health, called disability-adjusted life years, combines the estimates of years of life lost due to premature death and years lived in ill health or with disability to account for the total years of healthy life lost from disease and injury (AIHW 2019a).

In Australia, the total burden of disease rates increased as remoteness increased. Each remoteness area showed a similar pattern of increasing rates of burden in older age groups, with Remote and Very remote areas having the highest rates across all age groups. In 2015, the rates of total burden of disease were around twice as high for people aged 85 and over compared with those aged 65–84 (AIHW 2019a).

Risk factors

Health risk factors are characteristics or exposures that increase the likelihood of a person developing a disease or health disorder.

Based on the 2017–18 ABS National Health Survey, there was little difference in the prevalence of common health risk factors across remoteness areas. Across all remoteness areas, around 3 in 4 older people were overweight or obese based on measured body mass index, and more than 7 in 10 had high blood pressure (AIHW analysis of ABS 2019b) (Table 2D.2).

|

|

Major cities |

Inner regional |

Outer regional and Remote |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Exceeded lifetime alcohol risk guideline(a) |

15 |

16 |

17 |

|

Overweight or obese(b) |

75 |

78 |

78 |

|

High blood pressure(c) |

74 |

71 |

73 |

|

Did not meet physical activity guidelines(d) |

72 |

72 |

74 |

|

Current daily smoker |

7.1 |

6.5 |

7.1 |

|

Did not meet either fruit or vegetable guidelines(e) |

36 |

33 |

36 |

(a) National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2009 Guideline 1: Reducing the risk of alcohol-related harm over a lifetime, which recommends no more than 2 standard drinks per day.

(b) Based on measured height and weight and includes a body mass index of 25 and above.

(c) High blood pressure includes all persons with a high, very high or severe (from 140/90 mmHg) measured or imputed blood pressure (regardless of whether taking hypertension medication) as well as persons with normal/low (<140/90 mmHg) measured or imputed blood pressure who reported they were taking hypertension medication.

(d) The 2014 NHMRC Guidelines recommend that older Australians aged 65 and over should accumulate at least 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity on most, preferably all, days. This guideline is met where physical activity is completed 7 days in the last week and at least 30 minutes of physical activity is completed on at least 5 days in the last week. Data capture older Australians who did not meet this guideline and do not include people for whom this measure was not known or not applicable. Physical activity includes exercise at work, walking for fitness, recreation, or sport; walking to get to or from places; moderate exercise; and vigorous exercise (multiplied by 2) in the week prior to interview.

(e) Whether vegetable and fruit consumption met the recommended guidelines based on recommendations from the NHMRC Australian Dietary Guidelines (2013).

Notes:

- The above data are survey data and as such have a level of error attached to each estimate. Comparisons should be made with caution. Please refer to ABS 2019b for further information and relevant estimates of error.

- Data for Very remote areas are not included.

- 'Older people’ refers to people aged 65 and over.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019b.

For more information see Risk factors and Rural and remote health.

Aged care

Older people who live in Remote and Very remote areas can face more barriers to accessing aged care services than older people living in Major cities and regional areas. A range of demographic, geographical, climatic, cultural and socioeconomic factors contribute to the complexity of providing high-quality aged care services, especially in rural and remote communities (RDAA 2017).

The proportion of older Australians using mainstream higher level aged care services (that is, residential aged care and home care) tends to decrease as people live more remotely. This may reflect people in rural and remote areas moving to access higher level services that are not available in their community. Mainstream services tend to be concentrated in more densely populated areas, with almost two-thirds (62%) of permanent residential aged care facilities located in metropolitan areas and only 21% located in rural or remote areas (AIHW 2021a). By contrast, as people live more remotely, they tend to use more basic support services, such as home support assistance under the Commonwealth Home Support Programme. Additional care types, such as Multi-Purpose Services and the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Flexible Aged Care Program also cater to older Australians living in remote areas. At 30 June 2020, 89% of older Australians living in Very remote areas used home support services, compared with 70% living in Major cities (Table 2D.3) (AIHW 2020a).

Table 2D.3. Percentage of older people using aged care services by remoteness area, 30 June 2020

|

|

Home support |

Residential aged care |

Home care |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Major cities |

70 |

17 |

13 |

|

Inner regional |

74 |

14 |

12 |

|

Outer regional |

79 |

12 |

9.0 |

|

Remote |

86 |

6.9 |

6.8 |

|

Very remote |

89 |

3.8 |

7.4 |

Note: 'Older people' refers to people aged 65 and over.

Source: AIHW 2020a.

Compared with Major cities, the number of available places differ significantly for older people living remotely. In residential aged care, at 30 June 2020, 7 in 10 (71%) places were available in Major cities, followed by 21% in Inner regional areas, 7.6% in Outer regional areas and 0.6% in Remote and Very remote areas.

At 30 June 2020, the number of operational aged care services available in Remote and Very remote areas included:

- 43 residential aged care services, 1.6% of the national total

- 109 home care programs, 4% of the national total

- no transition care programs (AIHW 2020a).

For information on aged care services and places in Australia, see GEN Aged Care Data.

Social support

Social support can be formal or informal and includes emotional, personal and domestic support to individuals or groups. Informal social support is commonly provided by people close to the individual, such as friends, family and community. Formal social support refers to government and non-government services and programs. Unpaid care provided by family, friends and the community is invaluable, especially in regional and remote areas (Edwards et al. 2009).

Carers

In the 2018 ABS SDAC, an estimated 647,300 (17%) people aged 65 and over provided informal care and assistance within their household (18% of older men and 17% of older women were primary or secondary carers). Around 2 in 3 older Australians who identified as a carer during this period lived in Major cities (66%), 1 in 4 lived in Inner regional areas (25%) and 1 in 10 lived in Outer regional, remote and very remote areas (10%) (ABS 2019a).

Across remoteness areas, a similar proportion of older people identified as a carer:

- 17% in Major cities

- 17% in Outer regional, remote and very remote

- 19% in Inner regional (ABS 2019a).

Family and community support

Providing assistance and social support is significant to maintaining and supporting the health and independent functioning of older Australians. Broad activities such as mobility, self-care, oral communication, health care, cognitive or emotional tasks, household maintenance, meal preparation, reading or writing and private transport are recognised as activities where assistance or supervision may be required for older Australians (ABS 2019a). Assistance may be provided formally through services or informally through existing relationships, such as family members, friends or neighbours.

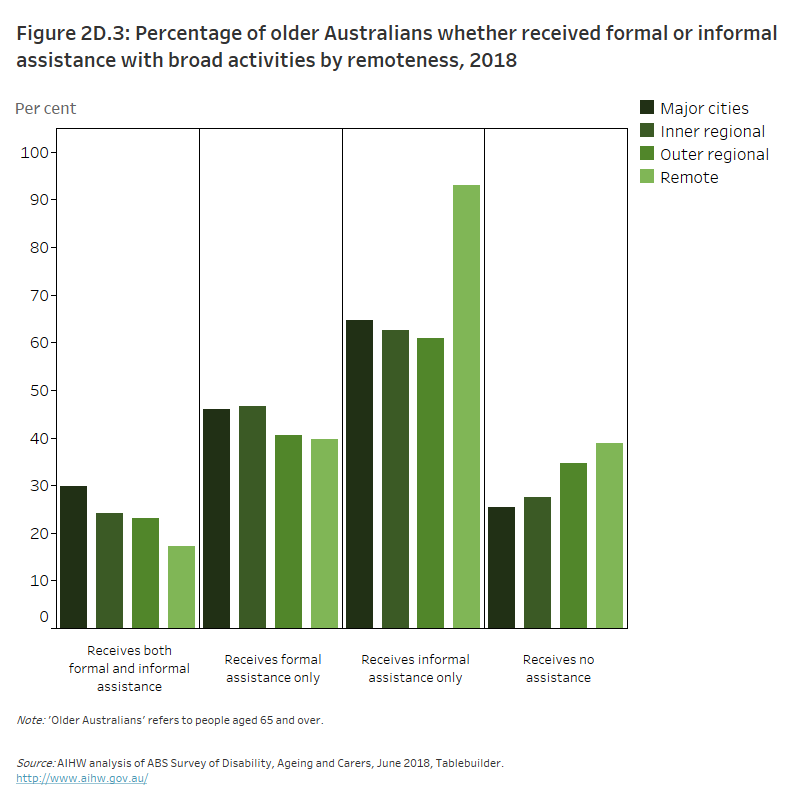

Based on the 2018 ABS SDAC:

- Around 2 in 7 (28%) older Australians (aged 65 and over) received both formal and informal assistance. However, as remoteness levels increased, older Australians were less likely to receive both kinds of support. Almost 1 in 3 (30%) older Australians in Major cities received both formal and informal assistance, compared with under 1 in 4 in both Inner regional (24%) and Outer regional, remote and very remote (23%*) areas.

- Almost 2 in 3 (64%) older Australians received only informal assistance. This did not differ substantially across Major cities (65%), Inner regional (63%) and Outer regional (61%) areas. However, in Remote and very remote areas, 9 in 10 (93%*) older Australians relied on only informal assistance.

- Nearly 1 in 2 older Australians (46%) received only formal assistance. Older Australians in Outer regional, remote and very remote areas were less likely to receive only formal assistance (41%*) compared with in Major cities (46%) and Inner regional areas (47%).

- Over 1 in 4 (27%) older Australians received no assistance. The proportion of those receiving no assistance varied by remoteness, with 1 in 3 (35%*) older Australians in Outer regional, remote and very remote areas, 2 in 7 in Inner regional areas (28%) and 1 in 4 in Major cities (25%) receiving no assistance (AIHW analysis of ABS 2019c) (Figure 2D.3).

In these points, asterisks (*) indicate that the estimate has a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution. Also note that proportions within regional areas do not add to 100%. For further information, see ABS 2019c.

The column graph shows, across all remoteness areas, the greatest proportion of older Australians receive informal assistance only. Older Australians in remote areas had the highest proportion of people receiving informal assistance only (93%). The proportion of people receiving no assistance was also highest in remote areas followed by outer regional areas (39% and 35%, respectively).

Volunteering

Volunteering provides a substantial benefit to communities and organisations. Volunteers bring new insights, enhance the image of an organisation and increase efficiencies, operations and effectiveness (AIHW 2021b). According to the 2014 ABS General Social Survey (GSS) (the most recent GSS data available that include age and remoteness breakdowns), an estimated 566,600 (30%) people aged 65 and over participated in unpaid voluntary work through an organisation in the last 12 months. Older people in more remote areas were more likely than their more urban counterparts to participate in volunteering: around 1 in 2 (49%*) older people living in Remote and very remote areas participated, 4 in 10 (41%) in Outer regional areas, 1 in 3 (32%) in Inner regional areas and 1 in 4 (27%) in Major cities (AIHW analysis of ABS 2015). (Note that estimate marked with asterisk (*) has a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution).

For more information on the social support of older Australians, see Social support.

Justice and safety

Elder abuse is a serious public health issue that can cause a range of physical, psychological and financial harms to older people. The prevalence of abuse among older Australians is largely unknown and there is a lack of information about the justice and safety of older Australians living in rural and remote communities. For information on the justice and safety of older Australians, see Justice and safety.

Housing and living arrangements

The housing and living arrangements of older people can have an impact on their health, economic status and overall wellbeing. Many older people live with family members; however, with changing circumstances – such as the loss of a spouse or a decline in health and functioning – living arrangements can change. According to the 2016 ABS Census:

- Around half (49%) of older people (aged 65 and over) in both Major cities and Remote and very remote locations lived with their spouse, compared with 55% of those in Inner regional areas and 54% in Outer regional areas.

- 2 in 7 (28%) older people in Remote and very remote areas lived alone, similar to 28% in Outer regional areas and 26% in both Inner regional areas and Major cities, respectively (AIHW analysis of ABS 2017).

- In 2016, older people aged 85 and over were more likely to live alone than their younger counterparts. The more remote the population, the greater the prevalence of people aged 85 years and over living alone: 44% of people lived alone in Major cities, 46% in Inner regional areas, 50% in Outer regional areas and 43% in Remote and very remote areas (AIHW analysis of ABS 2017).

For more information on the housing and living arrangements of older Australians see Housing and living arrangements.

Education and skills

The highest level of educational attainment of older Australians differs by remoteness. In Remote and very remote areas, 5 in 7 (72%) people aged 65 and over had an equivalent of year 12 or below as their highest education attainment, compared with 66% in Outer regional areas, 62% in Inner regional areas and 57% in Major cities (AIHW analysis of ABS 2017).

Older Australians in Major cities were more likely to have a bachelor degree or postgraduate qualification as their highest educational attainment compared with older Australians in Remote and very remote areas (16% and 5.6%, respectively) (AIHW analysis of ABS 2017).

For more information on the education and skills of older Australians, see Education and skills page.

Employment and work

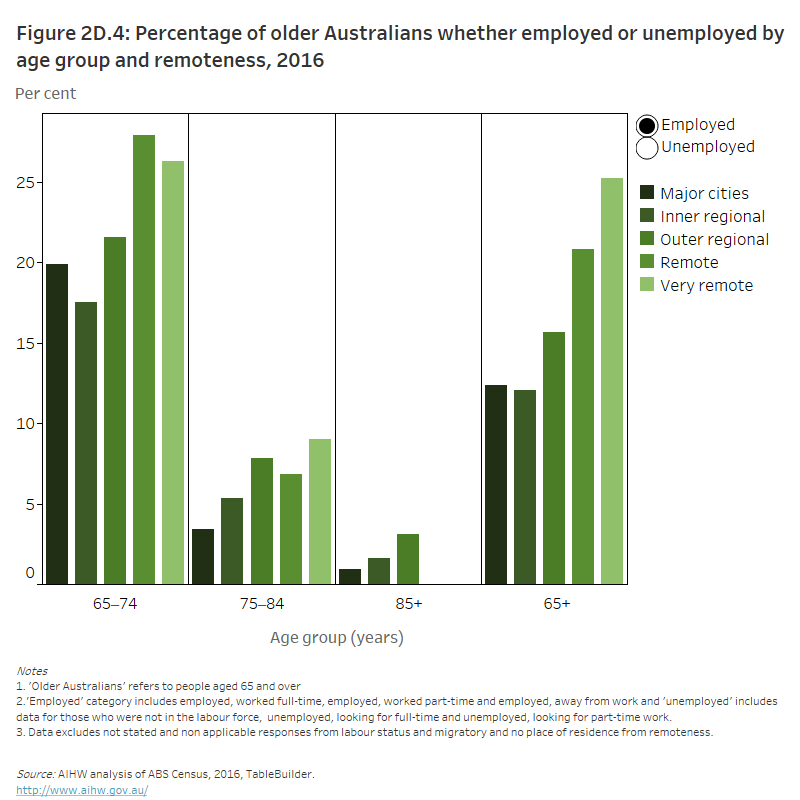

Some older Australians (aged 65 and over) participate in the workforce, with those in more remote areas more likely to do so. Around 1 in 6 (17%) older men were employed and participated in the workforce compared with 1 in 10 (9.2%) women in 2016.

According to the 2016 ABS Census:

- 1 in 4 (25%) people aged 65 and over in Very remote Australia were employed, compared with 12% in Major cities.

- The proportion of older people who were employed and worked full-time hours also increased with remoteness – 5% in Major cities, 4.6% in Inner regional areas, 7.2% in Outer regional areas, 11% in Remote and 15% in Very remote areas.

- Compared with those in Major cities, older Australians in Remote and Very remote areas were more than twice as likely to be employed on a full-time basis.

- Most (87%) older Australians in Major cities were not in the labour force compared with almost three-quarters (75%) of older people in Very remote areas (AIHW analysis of ABS 2017).

Across all remoteness areas, as age increased the proportion of people not participating in the workforce increased. In Major cities, 4 in 5 (80%) people aged 65–74 were not in the labour force compared with 96% aged 75–84 and 99% of those 85 and over. In Remote and Very remote areas, all people aged 85 and over were not participating in the workforce (Figure 2D.4).

Figure 2D.4: Proportion of older Australians whether employed or unemployed by age and remoteness, 2016

The column graph shows that the proportion of older Australians employed is highest in Remote and Very remote areas (21% and 25% respectively). The proportion of unemployed older Australians was highest in Major cities and Inner regional areas (both 88%).

For more information about the work and employment of older Australians see Employment and work.

Income and finances

Generally, the main sources of income for older people (aged 65 and over) are government pension or allowance, followed by superannuation and wages or salary. According to the 2018 ABS SDAC, nearly 2 in 3 (63%) older Australians in Outer regional and Remote and very remote areas received a pension or allowance as their main source of income, 15% received superannuation and 7.5% received wages or salary (AIHW analysis of ABS 2019c).

For more information on the income and finances of older Australians, see Income and finances.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on older Australians living in regional and remote communities, see:

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2013. Microdata: Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers, 2012. ABS cat. no. 4430.0.30.002. AIHW analysis using TableBuilder. Canberra: ABS. Viewed March 2021.

ABS 2015. Microdata: General Social Survey, 2014. ABS cat. no. 4159.0.30.004. AIHW analysis using TableBuilder. Canberra: ABS. Viewed March 2021.

ABS 2016. Microdata: Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers, 2015. ABS cat. no. 4430.0.30.002. AIHW analysis using TableBuilder. Canberra: ABS. Viewed March 2021.

ABS 2017. Microdata: Australian Census Longitudinal Dataset, 2006–2011–2016. ABS cat. no. 2020.0. AIHW analysis using TableBuilder. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 30 March 2021.

ABS 2018a. Census of Population and Housing: reflecting Australia – stories from the Census, 2016. ABS cat. no. 2071.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed March 2021.

ABS 2018b. Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2016. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 30 March 2021.

ABS 2018c. National Health Survey: first results 2017–18. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 31 March 2021.

ABS 2019a. Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: summary of findings, 2018. ABS cat. no. 4430. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 30 March 2021.

ABS 2019b. Microdata: National Health Survey 2017–18. ABS cat. no. 4324.0.55.001. AIHW analysis of TableBuilder. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 30 March 2021.

ABS 2019c. Microdata: Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers, 2018. ABS cat. no. 4430.0.30.002. AIHW analysis of TableBuilder. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 31 March 2021.

AIHW 2019a. Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2015. Cat. no. BOD 22. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 31 March 2021.

AIHW 2019b. Rural & remote health. Cat. no. PHE 255. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 31 March 2021.

AIHW 2020a. GEN Aged care data snapshot 2020 – third release. Canberra: GEN. Viewed 20 March 2021.

AIHW 2020b. Health of older people. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 31 March 2021.

AIHW 2020c. Mortality Over Regions and Time (MORT) books. Cat. no. PHE 229. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 31 March 2021.

AIHW 2021a. GEN fact sheet 2019–20: services and places in aged care. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 23 September 2021.

AIHW 2021b. Volunteers. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 07 April 2021.

Edwards, B, Gray, M, Baxter, J & Hunter, B. 2009. The tyranny of distance? Carers in regional and remote areas of Australia. Carers Australia and Australian Institute of Family Studies: Canberra.

Davis, S, & Bartlett, H 2008. Review article: healthy ageing in rural Australia: issues and Challenges. Australasian Journal on Ageing 27(2):56–60. Viewed 31 March 2021.

NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research Council) 2009. Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol. Canberra: NHMRC. Viewed 2021.

NHMRC 2013. Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra: NHMRC. Viewed 2021.

NHMRC 2020. Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol. Canberra: NHMRC. Viewed 2021.

NRHA (National Rural Health Alliance) 2011. Improving the prospects for healthy ageing and aged care in rural and remote Australia. Canberra: NRHA. Viewed 31 March 2021.

RDAA (Rural Doctors Association of Australia) 2017. Aged care in rural and remote Australia. Canberra: RDAA. Viewed 31 March 2021.