Onset of labour

Labour can occur spontaneously or may be induced by medical or surgical intervention. Examples of medical inductions are oxytocin and prostoglandins, examples of surgical inductions are artificial rupture of membranes and mechanical cervical dilation. Some women don’t have labour, such as when a caesarean section is performed before the onset of labour or a failed induction of labour.

Induction of labour is performed for a number of reasons related to both the mother and the baby, such as maternal or baby medical conditions and post-term pregnancy (Coates et al. 2020). Whilst most women who have induced labour – and their babies – do well, induction of labour increases the risk of infection and bleeding, and women reporting a less positive birth experience when compared to spontaneous labour (Coates et al. 2020; Grivell et al. 2012).

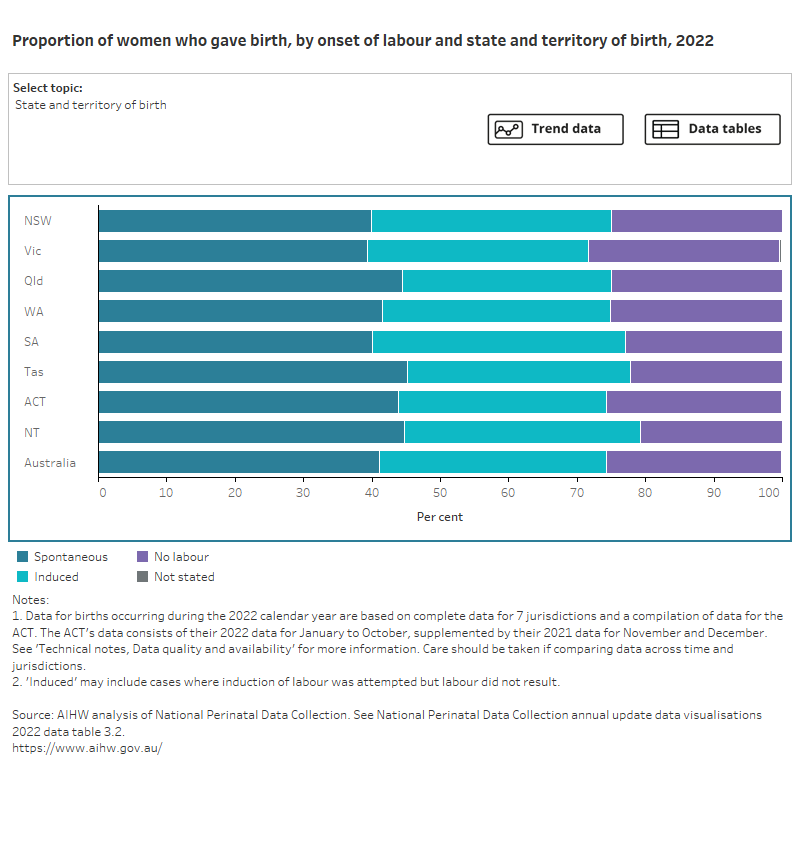

In 2022, 41% of mothers who gave birth had a spontaneous labour, 33% had an induced labour and 26% had no labour.

Figure 1 presents data on the onset of labour of women who gave birth, by selected maternal characteristics, for 2022. Select the trend button to see how data has changed over a 13-year period (where available).

Figure 1: Proportion of women who gave birth, by onset of labour and selected topic

Bar chart shows onset of labour by selected topics and a line graph shows topic trends between 2011 and 2021.

Labour onset varied by maternal age group. Teenage mothers (aged under 20) were the most likely to have spontaneous labour (53%), and mothers aged 40 or over were the most likely to have no labour onset (45%).

Onset of labour varied considerably by the number of babies born from a single pregnancy, with women who had a multiple pregnancy being more likely to have no labour (61%) than women with a singleton pregnancy (25%).

The rate of spontaneous labour decreased between 2010 and 2020 (from 56% to 41%) and has remained stable since, at 41% in both 2021 and 2022. This corresponds to an increase in the rate of induced labour between 2010 and 2020 (from 25% to 36%). There has been a slight decrease in the rate of induction since 2020 (34% in 2021 and 33% in 2022). Between 2010 and 2022, the rate of no labour has steadily increased from 19% to 26%.

For related information see National Core Maternity Indicator Induction of labour.

For more information on onset of labour see National Perinatal Data Collection annual update data table 2.26.

Induction type and reason

For mothers whose labour was induced, oxytocin was most commonly used (75 per 100 women who gave birth and had an induction). Noting that a combination of medical and/or surgical types of induction can be reported.

In 2022, the main reasons for inducing labour were diabetes (16%), pre-labour rupture of membranes (10%) and prolonged pregnancy (10%).

For more information on induction type and reason see National Perinatal Data Collection annual update data tables 2.27 and 2.28 and National Perinatal Data Collection annual update data visualisations table 3.2.

Augmentation of labour

Once labour starts, it may be necessary to intervene to speed up or augment the labour. Labour was augmented for 15% of mothers in 2022 (27% of mothers with spontaneous onset of labour). The augmentation rate was higher among first-time mothers, at 38% of those with spontaneous labour onset, compared with 19% of mothers who had given birth previously. Data excludes Western Australia.

For more information on augmentation of labour see National Perinatal Data Collection annual update data table 2.25.

References

Coates D, Makris A, Catling C, Henry A, Scarf V, Watts N, Fox D, Thirukumar P, Wong V, Russell H and Homer C (2020) ‘A systematic scoping review of clinical indications for induction of labour’, PLOS One, 15(1):e0228196, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0228196.

Grivell RM, Reilly AJ, Oakey H, Chan A and Dodd JM (2012) ‘Maternal and neonatal outcomes following induction of labor: a cohort study’, ACTA Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 91(2):198–203, doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01298.x.