Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease

Page highlights:

How many Australians have rheumatic heart disease?

- In 2019, there were 5,385 people living with rheumatic heart disease recorded on registers in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory.

- There were 4,600 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease in 2020–21.

- In 2020–21, the rate of hospitalisation for acute rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease among Indigenous Australians was 7 times as high as the non-Indigenous rate.

Acute rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease was the underlying cause of 338 deaths in 2019.

Acute rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease was the underlying cause of 338 deaths in 2019.

What are acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease?

Acute rheumatic fever

Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) is an autoimmune response to an infection of the upper respiratory tract by group A streptococcus bacteria. The infection can cause inflammation throughout the body including the heart, brain, skin and joints.

ARF is rare among most Australians, but still has a substantial impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

Early detection and treatment can prevent the bacterial infection progressing to ARF. The risk of ARF recurrence is high following an initial episode, and repeated episodes increase the chance of long-term heart valve damage.

Rheumatic heart disease

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is permanent damage of the heart muscle or heart valves as a result of ARF. RHD reduces the ability of the heart to pump blood effectively around the body, leading to symptoms such as shortness of breath after physical activity, fatigue and weakness. Severe forms can result in serious incapacity or death.

Symptoms of RHD can also occur with other heart conditions, making a diagnosis more difficult. Signs of damage detected by echocardiography and a history of ARF are both important clinical indicators for RHD diagnosis.

Risk factors and prevention of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease

ARF and RHD are closely associated with social and environmental factors such as poverty, overcrowding, and reduced access to health care.

Secondary prevention of the progression from ARF to RHD relies on correct diagnosis, to enable commencement of regular antibiotic preventive medication. Guidelines recommend admission to hospital for clinical investigation and confirmation of the diagnosis of ARF (RHD Australia 2020).

Effective prevention, diagnosis and treatment remain a challenge in remote Indigenous communities. Under the Rheumatic Fever Strategy (RFS), the Australian Government provides funding to support RHD control programs in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory.

Notifications of acute rheumatic fever

There were 2,244 notifications of ARF were recorded in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory in 2015–2019 (4.7 per 100,000 population) (AIHW 2021). Of these:

- 95% (2,128 ARF notifications) were recorded among Indigenous Australians – a rate of 96 per 100,000 population over 2015–2019

- ARF was more common among Indigenous females than males, and rates were highest among Indigenous people aged 5–14 (1,029 notifications, 208 per 100,000)

- the number and rate of notifications has increased – from 342 (3.7 per 100,000) in 2015 to 477 (5.0 per 100,000) in 2019.

How many Australians have rheumatic heart disease?

As at 31 December 2019, there were 5,385 (56 per 100,000 population) people living with RHD recorded on registers in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory (AIHW 2021).

Of these:

- 81% were Indigenous Australians (4,337 diagnoses, 955 per 100,000 population)

- 39% were aged under 25 (1,558 diagnoses)

- 66% were female (3,561 diagnoses)

- Northern Territory had the highest prevalence (2,308 diagnoses, 938 per 100,000).

Of those RHD diagnoses with severity status recorded, 41% had mild disease (2,206 diagnoses), while 28% had severe disease (1,532).

Older people were more likely to have severe RHD, with 42% aged 45 or over having severe disease (777 diagnoses), compared to 16% of those aged 15–24 (173 diagnoses).

New rheumatic heart disease diagnoses

In 2015–2019, there were 1,776 new RHD diagnoses in Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory (3.7 per 100,000 population).

Of these, 75% (1,325) were Indigenous Australians (60 per 100,000 population).

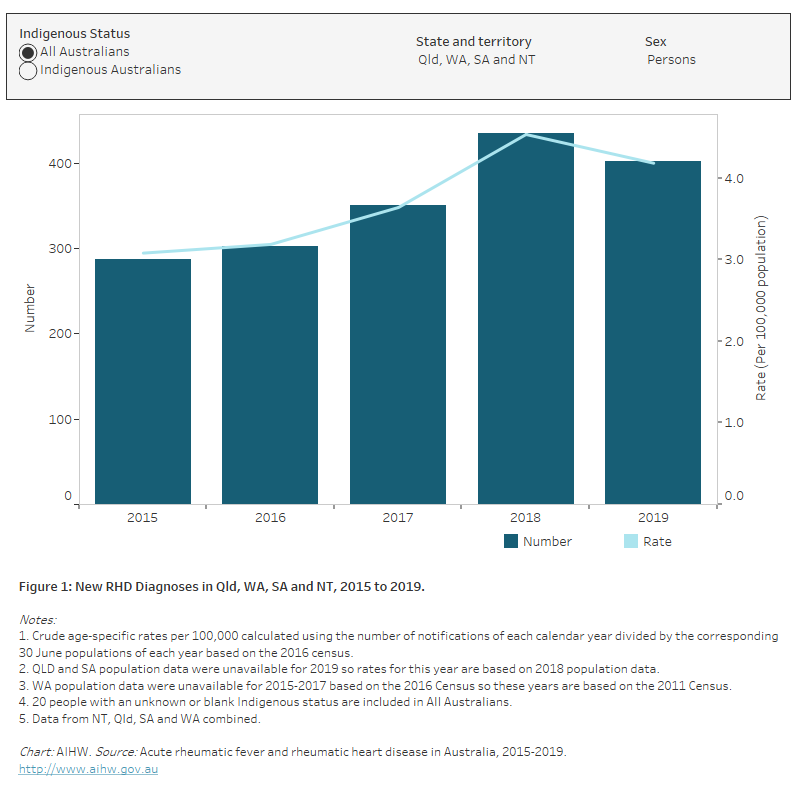

For the 4 jurisdictions combined, RHD diagnosis rates between 2015 and 2019 have remained relatively stable, at around 3–4 diagnoses per 100,000 population annually (Figure 1).

During this period, diagnosis rates varied by state and territory, but in general:

- South Australia had less than 1 diagnosis per 100,000 population

- Western Australia and Queensland had 2–5 diagnoses per 100,000

- Northern Territory had 40–60 diagnoses per 100,000.

Figure 1: New RHD diagnoses in Qld, WA, SA and NT, 2015 to 2019

The bar chart shows the number and rate of new rheumatic heart disease diagnoses in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory in 2015-2019. Among all Australians in these four states and territories combined, there was an increase in the age-standardised rate of new rheumatic heart disease diagnoses between 2015 and 2018 (3.1 to 4.5 per 100,000 population). The age-standardised rate of new rheumatic heart disease diagnoses was consistently higher among Indigenous Australians compared to the total Australian population.

Hospitalisations

Because hospital records may not always distinguish between ARF and RHD, the 2 diseases are here grouped together.

In 2020–21, there were 4,600 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of ARF or RHD – 0.8% of all cardiovascular disease (CVD) hospitalisations, and equating to an age-standardised rate of 18 hospitalisations per 100,000 population.

Age and sex

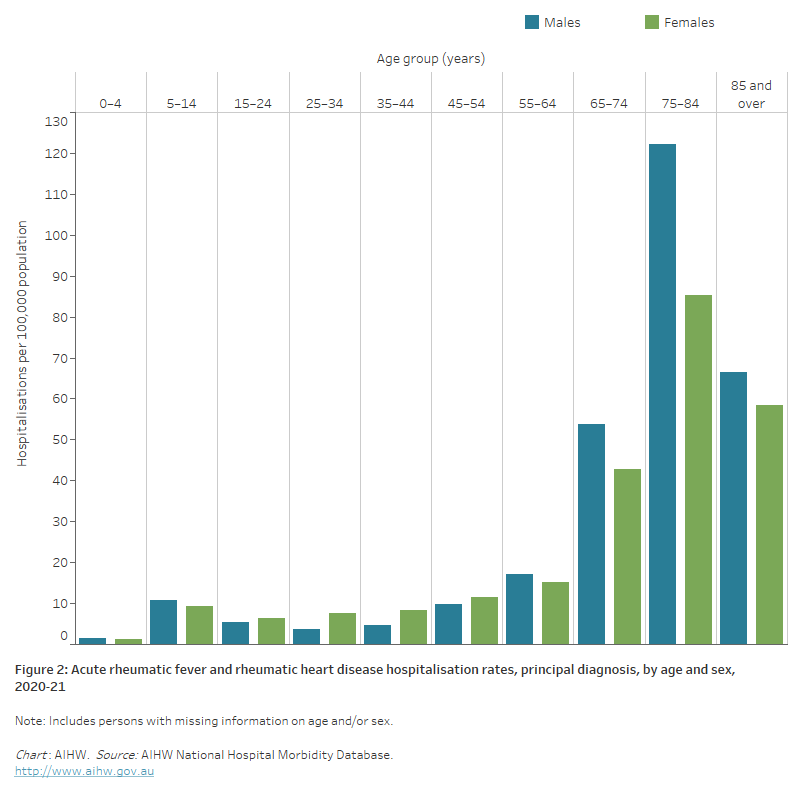

In 2020–21, where ARF or RHD was recorded as the principal diagnosis, hospitalisation rates:

- were similar for males and females after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations

- were higher for females than males aged 15–54, but higher for males aged 0–14 and 55 and over (Figure 2)

- were highest among males and females aged 75–84―around twice as high as those aged 65–74.

Figure 2: Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease hospitalisation rates, principal diagnosis, by age and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows in 2020–21 acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease hospitalisation rates were highest among males and females aged 75–84 years with 122 and 85 hospitalisations per 100,000 population, respectively.

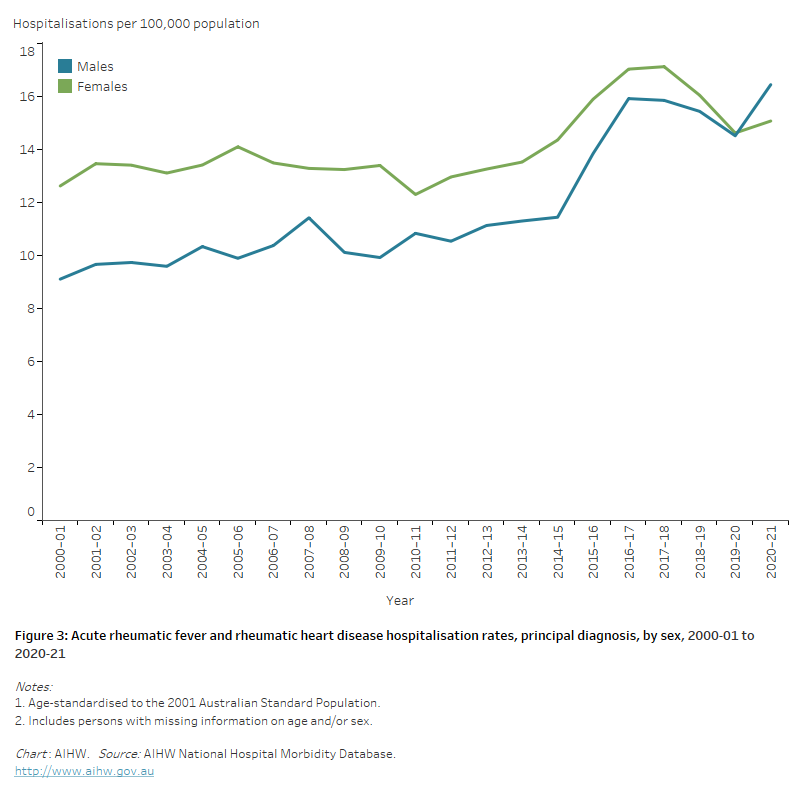

Trends

Between 2000–01 and 2020–21 the number of hospitalisations with ARF or RHD increased from 2,100 to 4,600. Over this period the age-standardised hospitalisation rate for ARF and RHD increased from 10.8 to 15.7 per 100,000 population. Females generally had higher rates than males, although the difference decreased over time and the male rate was higher in 2020–21 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease hospitalisation rates, principal diagnosis, by sex, 2000–01 to 2020–21

The line chart shows the overall increase in age-standardised acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease hospitalisation rates between 2000–01 and 2020–21 from 9.1 to 16.5 and 12.6 to 15.1 per 100,000 population for males and females, respectively.

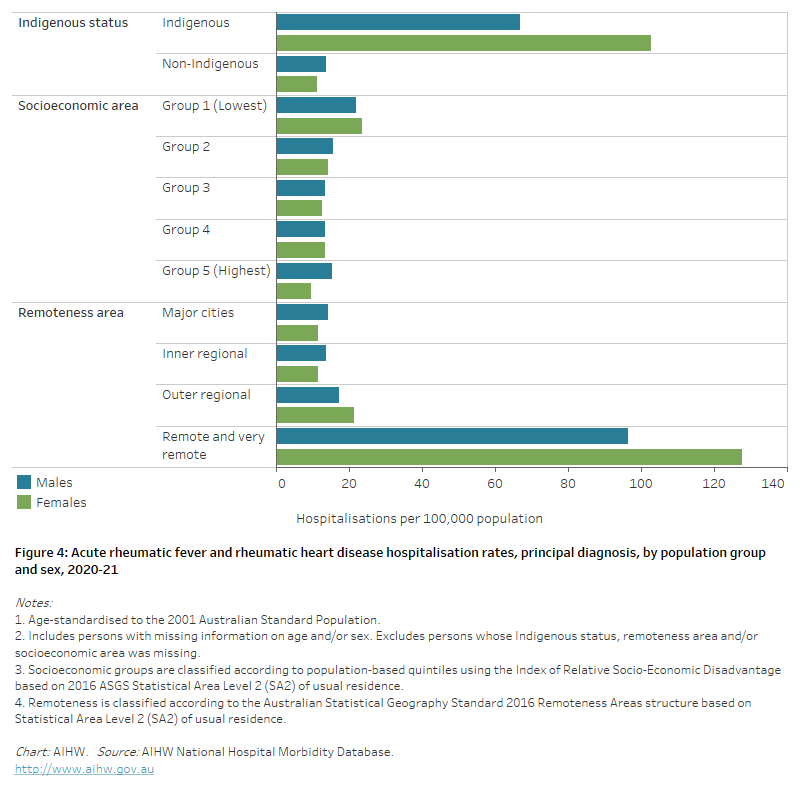

Variation among population groups

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2020–21, there were around 760 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of ARF or RHD among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, a rate of 88 per 100,000 population.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations:

- the rate among Indigenous Australians was 7 times as high as the non-Indigenous rate

- the disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians was greater for females than males—9 times as high for females and 5 times as high for males (Figure 4).

Socioeconomic area

In 2020–21, the ARF and RHD hospitalisation rate was 1.9 times as high for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with those in the highest socioeconomic areas.

The difference was greater for females (2.5 times as high) than males (1.4 times as high) (Figure 4).

Remoteness area

In 2020–21, age-standardised ARF and RHD hospitalisation rates were 8.6 times as high among those living in Remote and very remote areas compared with those in Major cities (Figure 4).

The high Remote and very remote rates reflect both the high proportion of Indigenous Australians living in these areas and that Indigenous Australians in remote areas continue to experience new cases of ARF and RHD, often at a young age. In non-remote areas, hospitalisations with ARF and RHD occur mostly among older people.

Figure 4: Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease hospitalisation rates, principal diagnosis, by population group and sex, 2020–21

The horizontal bar chart shows in 2020–21 age-standardised acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease hospitalisation rates were higher among Indigenous Australians, people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas and people living in Remote and very remote areas.

Deaths

Deaths from ARF and RHD are uncommon in Australia, and, as with hospitalisations, death records may not distinguish well between ARF and RHD. Here, the 2 conditions are here presented together.

In 2021, ARF or RHD was the underlying cause of 338 deaths, representing 0.2% of all deaths and 0.8% of CVD deaths, and equivalent to 1.3 deaths per 100,000 population.

Age and sex

Unlike many other forms of CVD, more females die from ARF and RHD than males. In 2021, females accounted for 60% of ARF and RHD deaths – 210 compared with 128 for males.

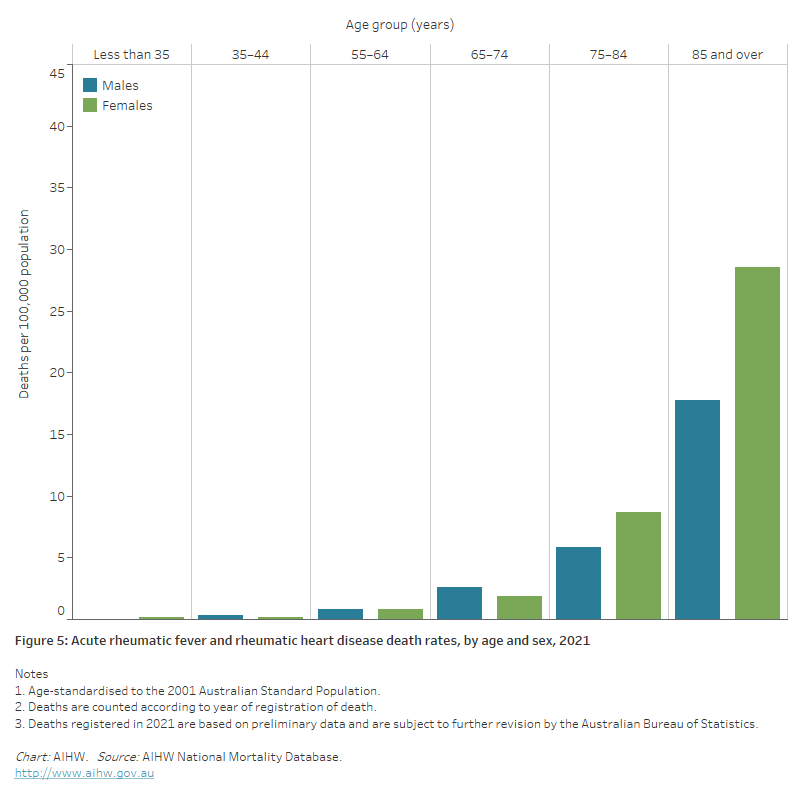

In 2021, ARF and RHD death rates:

- were 1.4 times as high for females than males

- increased with age, with two-thirds (68%) of all ARF and RHD deaths occurring in those aged 75 and over. ARF and RHD death rates for males and females were highest in the 85 and over age group — 3.1 times as high for males and 3.3 times as high for females aged 75–84 (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease death rates, by age and sex, 2021

The bar chart shows in 2021 acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease death rates were highest among males and females aged 85 and over, at 18 and 29 per 100,000 population, respectively.

Trends

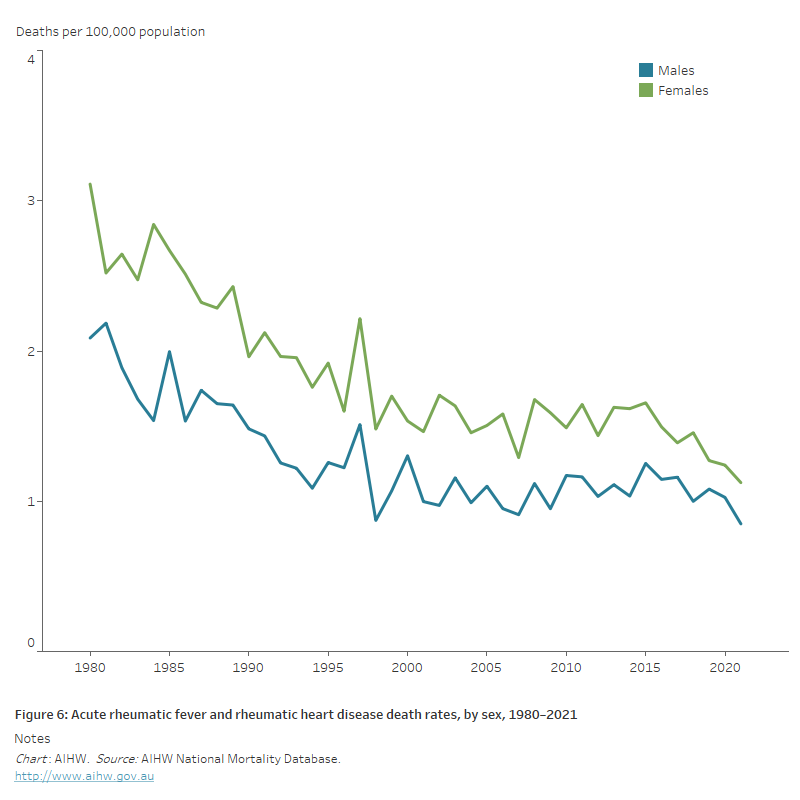

Between 1980 and 2021:

- the number of ARF and RHD deaths increased by 10%, from 306 to 338

- the age-standardised ARF and RHD death rate declined by 63%, falling from 2.7 to 1.0 deaths per 100,000 population (Figure 6). Much of the decline occurred before 2000.

Figure 6: Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease death rates, by sex, 1980–2021

The line chart shows the decline in age-standardised acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease death rates between 1980 and 2021 from 2.1 to 0.8 and 3.1 to 1.1 for males and females, respectively.

Variation among population groups

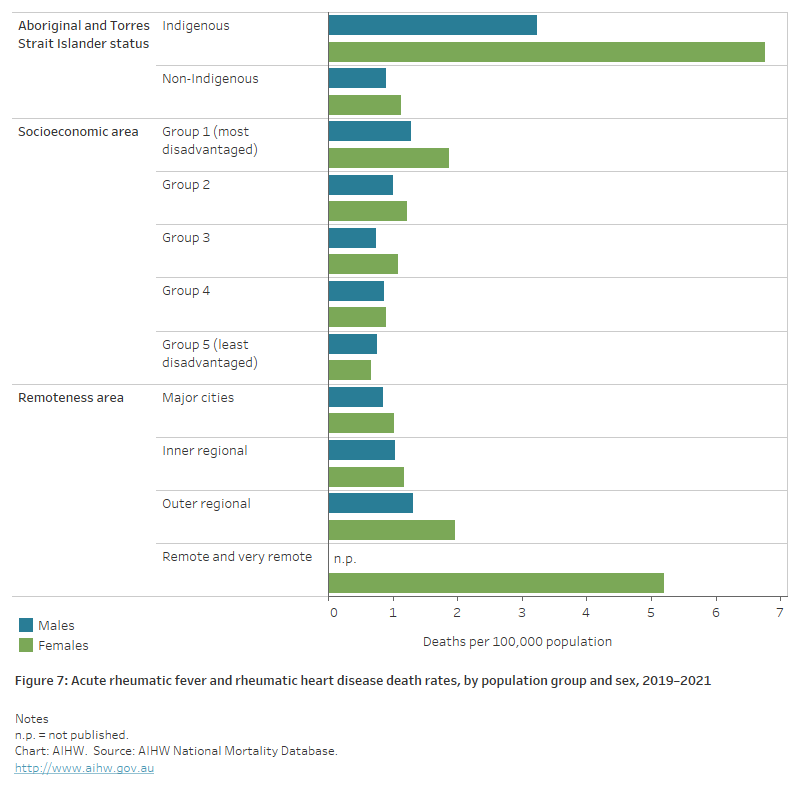

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2019–2021, there were 72 deaths from ARF or RHD among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in jurisdictions with adequate identification of Indigenous status, a rate of 3.2 per 100,000 population.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations, the ARF and RHD death rate for Indigenous people was 5.2 times as high as that for non-Indigenous people.

Indigenous males and females had ARF and RHD death rates 3.6 times and 6.2 times as high as non-Indigenous males and females (Figure 7).

In the 25–64 age group, the Indigenous death rate was 17 times as high as the non-Indigenous rate.

Socioeconomic area

In 2019–2021, the age-standardised ARF and RHD death rate was 2.3 times as high for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with those living in the highest socioeconomic areas.

The rate for males was 1.6 times as high, and for females 2.7 times as high (Figure 7).

Remoteness area

In 2019–2021, age-standardised death rates for ARF and RHD increased with remoteness, from 1.0 deaths per 100,000 population in Major cities to 3.6 per 100,000 in Remote and very remote areas (Figure 7).

The differences between regions are closely related to Indigenous status. In Remote and very remote areas, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people comprise a high proportion of the overall population, and patterns of deaths across age groups seen among Indigenous Australians resemble those of the most remote areas.

Figure 7: Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease death rates, by population group and sex, 2019–2021

The horizontal bar chart shows in 2019–2021 age-standardised acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease death rates were higher among Indigenous Australians, people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas and people living in Remote and very remote areas.

Deaths among Australians with RHD

In 2017–2021, 595 deaths were reported for people with RHD who were listed on one of the four jurisdictional registers in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory (AIHW 2023). Note that people with RHD may have died of any cause, and that cause-of-death is not captured on most registers.

Of these, 382 people (64%) were Indigenous Australians. The median age of death was 51 years for Indigenous males and 56 years for Indigenous females, compared with 73 years for non-Indigenous males and 74 years for non-Indigenous females.

References

AIHW (2023) Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia, 2017-2021. AIHW cat. no. CVD 99. Canberra: AIHW.

RHD Australia (2020) The 2020 Australian guideline for the prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease (3rd ed.). Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research.