Medicine use

Page highlights:

- In 2020–21, over 16.5 million prescriptions were dispensed for diabetes medicines through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, representing 5.3% of total prescriptions.

- Prescriptions dispensed through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme for diabetes medicines increased by 24% between 2017–18 and 2020–21, from 13.4 million to 16.5 million.

- In 2021, 31,700 people began using insulin to treat their diabetes. Around 15,600 people living with type 2 diabetes initiated insulin therapy (1,700 per 100,000 population).

- The incidence of insulin therapy in people living with type 2 diabetes was highest for both males and females aged 10–39 and was 1.6 times as high for females compared with males, overall.

Management of gestational diabetes

Of all females (aged 15–49) diagnosed with gestational diabetes in 2020–21, at the time of giving birth, 49% were recorded as having managed their condition without medication using diet, exercise and/or lifestyle management; 39% had been treated with insulin therapy and 8.4% had been treated with oral hypoglycaemic medications.

Diabetes medicines

Diabetes medicines are key elements in preventing and treating diabetes and its risk factors. They are most commonly used to help manage blood glucose levels.

Types of diabetes medicines

People living with diabetes may require medications including insulin to help manage their blood glucose levels. All people with type 1 diabetes will require insulin. There are a variety of diabetes medicines used in Australia:

- Insulin: This is a hormone made by beta cells in the pancreas. Insulin is released into the blood stream where it helps to move glucose from food that is eaten into the body’s cells to be used as energy. Injectable insulin is provided to people living with diabetes to supplement or replace insulin produced by the body to help reduce the level of glucose in the blood.

- Biguanides: Also known as metformin, these are tablets which lower blood glucose levels by reducing the amount of stored glucose released by the liver, slowing the absorption of glucose from the intestine, and helping the body to become more sensitive to insulin so that its own insulin works better.

- Sulphonylureas: This group of tablets lower blood glucose levels by stimulating the pancreas to release more insulin.

- Thiazolidinediones: These medicines help to lower blood glucose levels by increasing the effect of the body’s own insulin, especially on muscle and fat cells.

- Alpha Glucosidase Inhibitors: These help to slow down the digestion and absorption of certain dietary carbohydrates.

- Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors: These inhibit the enzyme DPP-4 which enhances the levels of active incretin hormones and act to lower blood glucose levels by increasing insulin secretion and decreasing secretion of glucagon (a hormone that has the opposite effect of insulin, that is, by increasing blood glucose levels).

- Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1a): GLP-1 is a hormone that is produced in the body when you eat which stimulates the pancreas to secrete insulin to reduce blood glucose levels. Medicines belonging to the GLP-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1a) class mimic the effects of GLP-1 to reduce blood glucose level and are normally given as an injection.

- Sodium-glucose transporter (SGLT2) inhibitors: These are a class of tablet which lower plasma glucose concentrations by increasing renal excretion of glucose (Diabetes Australia 2021).

In 2020–21, there were over 16.5 million prescriptions dispensed for diabetes medicines through Section 85 of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) and Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (RPBS), representing 5.3% of total prescriptions. Over one third of those claims (5.4 million) were for metformin which was the seventh highest dispensed medicine, costing over $50 million from out-of-pocket payments and government subsidies.

Supply of diabetes medicines

The PBS and RPBS are Australian Government programs that subsidise approved prescriptions for medicines to make them more affordable. Medicines may be discounted through this subsidy and require a co-payment from the patient to reach the gap between the subsidy and the cost of the medicines. Some medicines are subsidised enough to be under the co-payment threshold and not require any further out-of-pocket costs to the person.

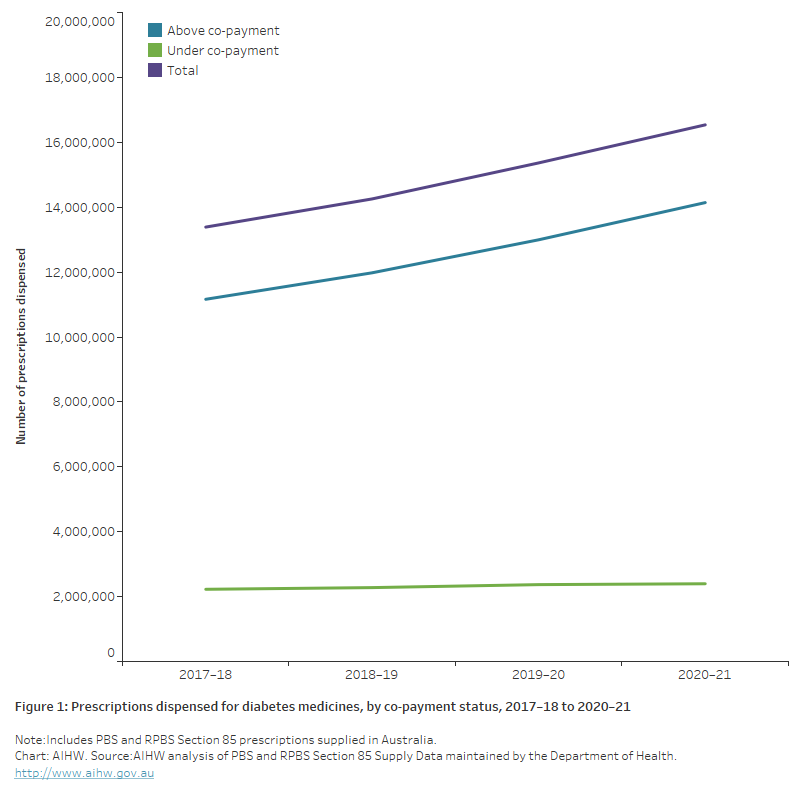

Prescriptions dispensed through the PBS for diabetes medicines increased by 24% between 2017–18 and 2020–21, from 13.4 million to 16.5 million (Figure 1). The increase across this period was due to PBS subsidised prescriptions which included an out-of-pocket expense for the person.

Prescriptions dispensed for diabetes medicines made up 5.3% of the total number of prescriptions dispensed in 2020–21, an increase of 18% from 2017–18 (4.5%).

Figure 1: Prescriptions dispensed for diabetes medicines, by co-payment status, 2017–18 to 2020–21

The chart shows the number of prescriptions dispensed for diabetes medicines, by co-payment status between 2017–18 and 2020–21. Over the period, diabetes medicines increased from 13.4 million to 16.5 million. The increase across this period was due to PBS subsidised prescriptions which included an out-of-pocket expense for the person.

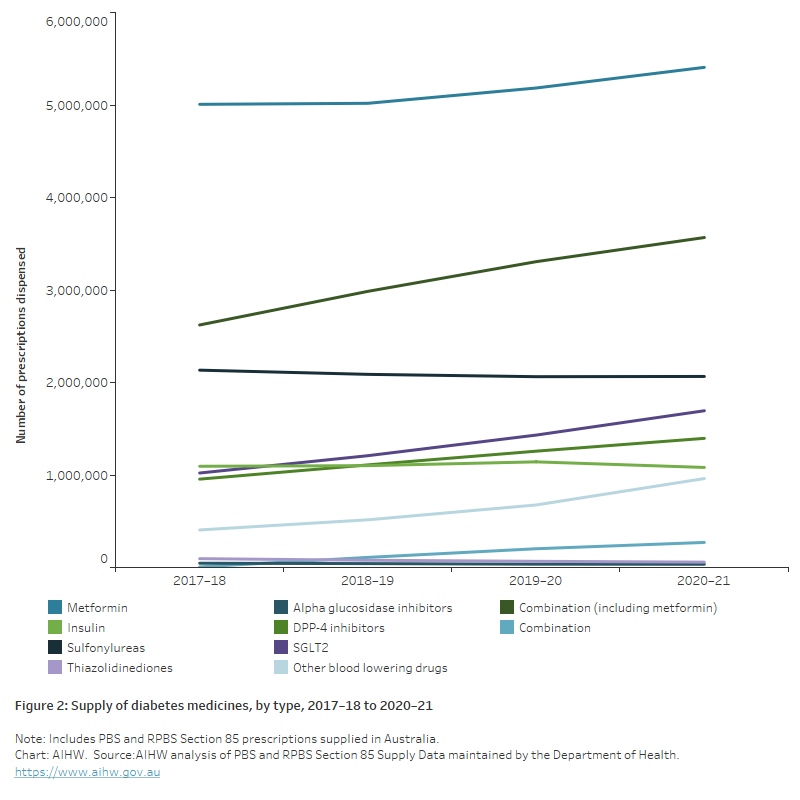

Overall, prescriptions dispensed for thiazolidinediones and alpha glucosidase inhibitors have been decreasing over time, and there was a small decrease in the number dispensed for insulin in 2020–21. All other diabetes medicines have recorded increasing prescriptions dispensed over time. Combination therapies and other blood glucose lowering medications such as I GLP-1a recorded the largest increases from 2017–18 to 2020–21 (36% and 136%, respectively) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Supply of diabetes medicines, by type, 2017–18 to 2020–21

Insulin use

Insulin is a hormone made by beta cells in the pancreas. For people living with type 1 diabetes, the body does not produce insulin and daily insulin injections or infusion via an insulin pump are required to survive. Not all people living with type 2 diabetes require insulin therapy initially, but most will require some form of insulin treatment to maintain blood glucose levels over time. For people with type 2 diabetes, insulin is now considered a second-line therapy after initial treatment with metformin, depending on the clinical context, and early intervention with insulin can be beneficial for long-term outcomes in some patients (Wong and Tabet 2015).

All diabetes

In 2021, 31,700 people registered on the National (insulin-treated) Diabetes Register (NDR) began using insulin to treat their diabetes. Of these:

- around 3,000 (9.5%) people were diagnosed with type 1 diabetes

- 15,600 (49%) people began using insulin to treat type 2 diabetes

- 12,300 (39%) females began using insulin to treat gestational diabetes

- 589 (1.9%) people began using insulin to treat other forms of diabetes.

- 253 (0.8%) people began using insulin for whom diabetes type was unknown.

Due to rounding, percentages do not sum to 100.

Type 2 diabetes

In 2021, around 15,600 people living with type 2 diabetes initiated insulin therapy according to the National (insulin-treated) Diabetes Register (1,700 per 100,000 population).

Age and sex

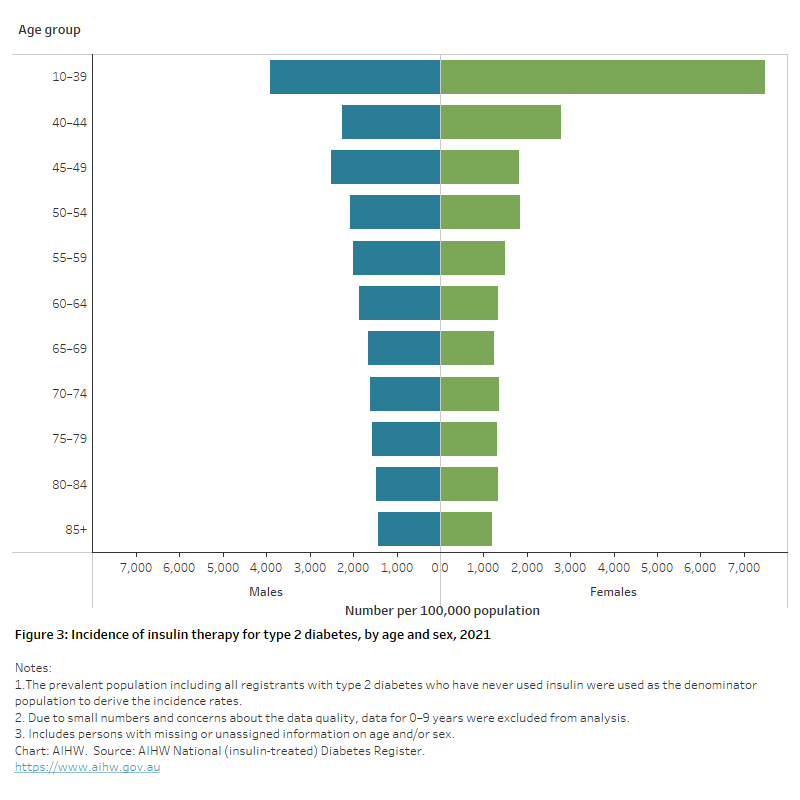

In 2021, the incidence of insulin therapy in people living with type 2 diabetes was:

- highest for both males and females aged 10–39 (3,900 and 7,500 per 100,000 population, respectively) and decreased with age (Figure 3)

- 4.2 times as high in people aged 10–39 as those aged 85 and higher (5,500 and 1,300 per 100,000 respectively)

- higher for males compared with females from age 45 onwards (Figure 3)

- overall, 1.6 times as high for females compared with males after adjusting for the different age structures of the population.

Figure 3: Incidence of insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes, by age and sex, 2021

The chart shows the incidence of insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes by age group in 2021. Rates were highest in males and females aged 10–39 (3,900 and 7,500 per 100,000 population, respectively).

Trends over time

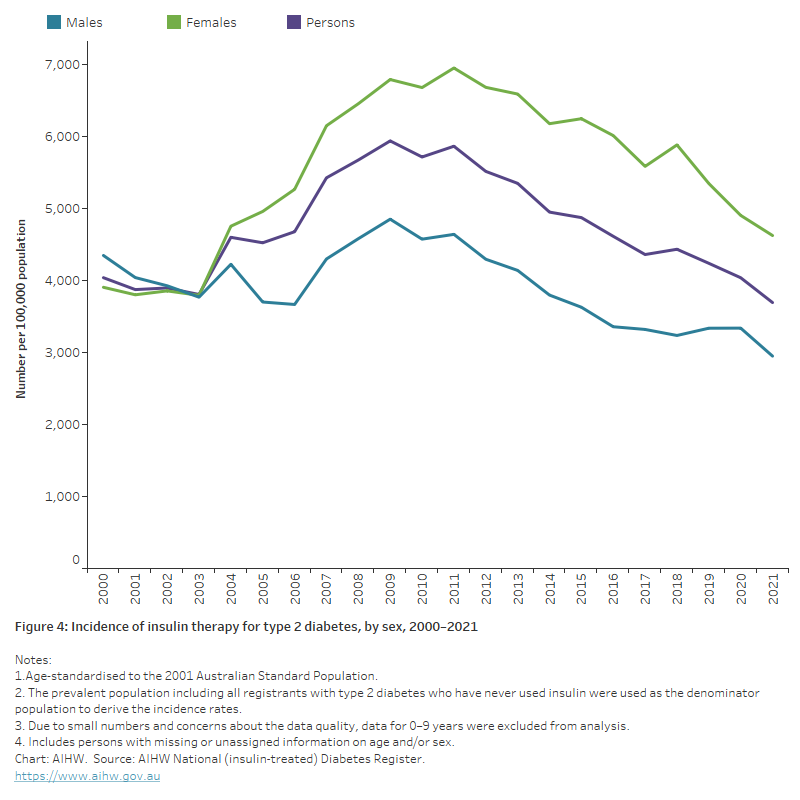

After controlling for the age structure of the population, the incidence of insulin therapy for people living with type 2 diabetes decreased overall between 2000 and 2021 (down 8.5%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Incidence of insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes, by sex, 2000-2021

The chart shows a decline in the incidence rate of insulin therapy for people living with type 2 diabetes between 2000 and 2021 from around 4,000 to 3,700 per 100,000 population.

Variation between population groups

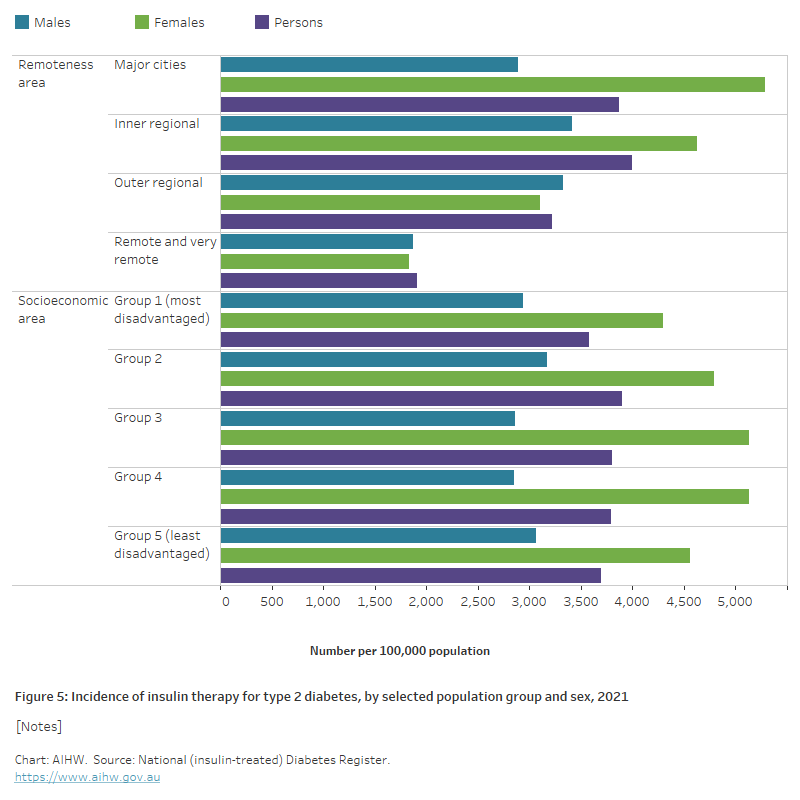

In 2021, the age-standardised incidence of insulin therapy for people living with type 2 diabetes:

- was higher among those living in Major cities and Inner regional areas compared with Outer regional and Remote and very remote areas

- was similar among socioeconomic areas (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Incidence of insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes, by selected population groups and sex, 2021

The chart shows that for males and females the incidence of insulin therapy in people living with type 2 diabetes in 2021, was lower among people living in remote and very remote areas, and similar among socioeconomic areas.

Note: Incidence rates of insulin-treated type 2 diabetes for Indigenous Australians have been excluded from this report, as the NDR may underestimate the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with diabetes registered. For more information see the ‘Methods and classifications’ section of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s Incidence of insulin-treated diabetes in Australia report.

Management of gestational diabetes

Of all females (aged 15–49) diagnosed with gestational diabetes in 2020–21, at the time of giving birth in hospital:

- 49% were recorded as having managed their condition without medication using diet, exercise and/or lifestyle management.

- 39% had been treated with insulin therapy.

- 8.4% had been treated with oral hypoglycaemic (blood glucose lowering) medications.

- The treatment type for 3.5% was unspecified.

Variation by age

In 2020–21, females who managed their gestational diabetes:

- without the use of medication were more likely to be younger, with those aged 15–19 being 1.4 times as likely to manage their condition using diet, exercise and/or lifestyle modifications compared with those aged 45 and over

- with the use of oral hypoglycaemic medications were more likely to be younger, with those aged 15–19 being 2.1 times as likely as those aged 45 and over to use this treatment type

- with the use of insulin (an indication of increasing gestational diabetes severity) were more likely to be older with those aged 45 and over being 2.5 times as likely to require this treatment type than those aged 15–19.

References

Diabetes Australia (2021) Medicine to treat diabetes, Diabetes Australia website, accessed 15 December 2021.

Wong J and Tabet E (2015) 'The introduction of insulin in type 2 diabetes mellitus', Australian Family Physician, 44(5):278–83, PMID: 26042399.