1. Smoking during pregnancy

Why are smoking in pregnancy rates important?

Smoking in pregnancy is an important modifiable risk factor for low birthweight, pre-term birth, placental complications and perinatal mortality. Tobacco smoke reduces the flow of oxygen to the placenta and exposes the fetus to a number of toxins (Knopik et al. 2012; Milner et al. 2007).

Smoking during pregnancy can also impact the infant or developing child, with children whose mothers smoked during pregnancy more likely to be affected by sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), childhood cancers, high blood pressure, asthma, obesity and lowered cognitive development (Julvez et al. 2007; Ng & Zelikoff 2006).

Poorer child health outcomes are associated with a higher number of cigarettes smoked during pregnancy. There were positive changes in smoking behaviour during the antenatal period, with around one-fifth (22%) of women who smoked quitting during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy (AIHW 2015). Quitting smoking, particularly within the first 20 weeks of pregnancy, may help to reduce some of the effects of smoking (Chan & Sullivan 2008). The AIHW’s perinatal dynamic data display also provides comparison of rates of smoking in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy compared to the second 20 weeks of pregnancy.

National Core Maternity Indicator 1 also reports on smoking in pregnancy, for those who reported smoking in the first 20 weeks and among those who reported smoking, the proportion who reported smoking after 20 weeks of pregnancy. This NCMI indicator includes disaggregations by hospital sector, remoteness, Indigenous status of the mother and disadvantage quintile. This information may be used alongside the children’s headline indicator to provide a more detailed picture of smoking in pregnancy in Australia.

Does smoking in pregnancy vary across population groups?

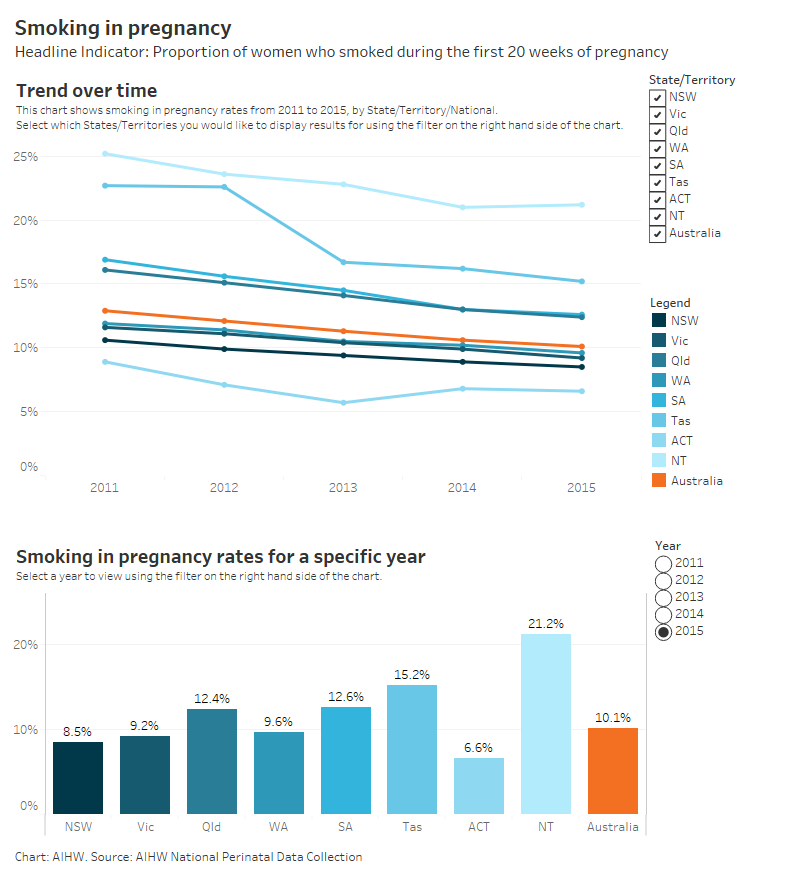

In 2015, around 1 in 10 (10.1%) mothers across Australia smoked during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy. The proportion of women who smoked during the first 20 weeks was highest among teenage mothers, with almost one third (32.3%) of mothers under the age of 20 reporting smoking during this period. The proportion decreased with increasing maternal age: 6.4%, 6.3% and 6.8% for mothers aged 30-34, 35-39, and 40 and over, respectively.

Age-standardised rates have been used for this indicator to present the data by Indigenous status to take into account differences in the age distribution of the two groups. The proportion of Indigenous women smoking during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy was 3.7 times as high (43.8%) as that for non-Indigenous women (11.7%). Mothers born in Australia (13.4%) were 3.8 times as likely to smoke during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy when compared to overseas born mothers (3.5%). Smoking rates were around 3.4 times as high for those mothers living in Remote or very remote areas (26.0%) compared to women living in Major cities (7.7%).

Has there been a change over time?

Smoking during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy was reported in Children’s Headline Indicators for the first time in 2011. The overall rate of women smoking during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy in 2015 (10.1%) is slightly lower compared to the rate in 2011 (12.9%). In fact, for every national disaggregation reported in the portal the proportion of women who smoked in the first 20 weeks has decreased each year, though sometimes by a small amount. The rate for women under the age of 20 has decreased slightly between 2011 and 2015, from 35.7% to 32.3%. The rate for Indigenous women was also slightly lower across the five years (43.8% in 2015 compared with 47.0% in 2011), as was the rate for women living in Remote and very remote areas (26.0% in 2015 compared with 29.4% in 2011), and in the lowest socioeconomic areas (17.9% in 2015 compared with 20.5% in 2012).

Notes

Smoking status in pregnancy is self-reported by the mother and is based on the first 20 weeks of pregnancy.

For Indigenous status of the mother, Indigenous and non-Indigenous proportions are directly age-standardised using the 2001 Australian female Estimated Resident Population (ERP) population as the standard population.

Age-standardisation is a method of removing the influence of age when comparing populations with different age structures. The age structures of the different populations are converted to the same ‘standard’ structure, and then the disease rates that would have occurred with that structure are calculated and compared.

References

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2015. Australia's mothers and babies 2013 —in brief. Perinatal statistics series no. 31. Cat. no. PER 72. Canberra: AIHW.

Chan DL & Sullivan EA 2008. Teenage smoking in pregnancy and birthweight: a population study, 2001–2004. Medical Journal of Australia 188(7):392–6.

Julvez J, Ribas-Fito N, Torrent M, Forns M, Gracia-Esteban R & Sunyer J 2007. Maternal smoking habits and cognitive development of children at age 4 years in a population-based birth cohort. International Journal of Epidemiology 36(4):825–32.

Knopik VS, Maccani MA, Francazio S & McGeary JE 2012. The epigenetics of maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy and effects on child development. Development and Psychopathology 24(4):1377-1390.

Milner AD, Rao H & Greenough A 2007. The effects of antenatal smoking on lung function and respiratory symptoms in infants and children. Early Human Development 83(11):707–11.

Ng SP & Zelikoff JT 2006. Smoking during pregnancy: subsequent effects on offspring immune competence and disease vulnerability in later life. Reproductive Toxicology 23(3):428–37.