Rural and remote health

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2024) Rural and remote health, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 03 May 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2024). Rural and remote health. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-remote-australians/rural-and-remote-health

MLA

Rural and remote health. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 30 April 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-remote-australians/rural-and-remote-health

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Rural and remote health [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024 [cited 2024 May. 3]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-remote-australians/rural-and-remote-health

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2024, Rural and remote health, viewed 3 May 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-remote-australians/rural-and-remote-health

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

Around 7 million people – or 28% of the Australian population – live in rural and remote areas, which encompass many diverse locations and communities (ABS 2023h). These Australians face unique challenges due to their geographic location and often have poorer health outcomes than people living in metropolitan areas. Data show that people living in rural and remote areas have higher rates of hospitalisations, deaths and injury and also have poorer access to, and use of, primary health care services, than people living in Major cities.

This report uses 2 remoteness structure classification systems.

The Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) Remoteness Structure (ABS 2021) defines remoteness areas in 5 classes of relative remoteness:

- Major cities

- Inner regional

- Outer regional

- Remote

- Very remote.

These remoteness areas are centred on the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia, which is based on the road distances people have to travel for services (ABS 2021).

This report uses the term ‘rural and remote’ to cover any area outside of Australia’s Major cities. Due to small population sizes, data for Outer regional and remote and Remote and very remote areas are sometimes combined for reporting.

The Modified Monash Model (MMM) (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023b) is based on the ASGS Remoteness Structure and also town size. It classifies metropolitan, regional, rural and remote areas in Australia into seven categories:

- MM 1: Metropolitan areas

- MM 2: Regional centres

- MM 3: Large rural towns

- MM 4: Medium rural towns

- MM 5: Small rural towns

- MM 6: Remote communities

- MM 7: Very remote communities

Areas classified MM 2 to MM 7 are considered to be rural or remote.

The MMM was developed to better target health workforce programs and to attract health professionals to more remote and smaller communities. This report uses the MMM for presentation of access to primary health care and health workforce data.

Profile of rural and remote Australians

Most Australians live in Major cities than in regional or remote areas. As at 30 June 2022, the proportion of Australians by area of remoteness was:

- 72% in Major cities

- 18% in Inner regional areas

- 8.1% in Outer regional areas

- 1.2% in Remote areas

- 0.8% in Very remote areas (ABS 2023h).

First Nations people

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people are more likely to live in urban and regional areas compared with more remote areas. However, the proportion of the total First Nations population increases with remoteness from 1.9% in Major cities, to 32% in Remote and very remote areas based on estimated Indigenous population projections for 2021 (AIHW 2023k).

For more information, see First Nations people.

Age

On average, people living in Inner regional and Outer regional areas are older than those in Major cities. For Inner regional areas, 22.1% of the population were aged 65 years or older in 2022 compared with 15.5% in Major cities, 14.7% in Remote and 10.3% in Very remote areas (ABS 2023h).

Figure 1: Australian population, by age group, sex and area of remoteness, 2022

This graph shows the age and sex for each of the remoteness areas by age groups 0-4, 5–14, 15–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84 and 85+. The graph shows that on average, people living in Remote and very remote areas are younger than those in Major cities. The highest proportion of older Australians aged 65+ live in Inner regional and Outer regional areas.

Note: Percentages for each remoteness area includes those from Other Territories.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2023h; Table S1.

Age standardisation

Health status, outcomes and service use are associated with age. This means that comparisons between population groups can be confounded by differences in their age distributions. Age-standardised rates are often used to compare outcomes for populations with different age structures, such as remoteness areas. As the purpose of this web report is to make comparisons between remoteness areas, age-standardised results have been used for health risk factors and chronic conditions, where possible. Unadjusted (crude) rates are available in the supplementary data tables and are often available in the referenced and/or linked reports.

Education

Increasing levels of education is shown to have an overall positive effect on an individual’s life satisfaction, particularly through the indirect effects of improved income and better health (AIHW 2023g).

In 2023, people aged 20–64 living in rural and remote areas were less likely than those in Major cities to have completed Year 12 or a non-school qualification (Figure 2; ABS 2023b). Around 3 in 5 people living in Inner regional (62%), Outer regional (59%) and Remote and very remote areas (59%) had completed Year 12, compared with 3 in 4 (78%) of those in Major cities (ABS 2023b). The gap in completion of year 12 between Major cities and Remote and very remote areas has narrowed slightly from 24% in 2014 to 19% in 2023 (Figure 2; ABS 2023b).

Similarly, a smaller proportion of people aged 20–64 living in Inner regional (27%), Outer regional (22%) and Remote and very remote areas (20%) had completed a bachelor’s degree or above in 2022, compared with those in Major cities (41%) (ABS 2023b). The gap in completion of a bachelor’s degree between Major cities and Remote and very remote areas has widened from 16% in 2014 to 21% in 2023 (Figure 2; Table S2; ABS 2023b).

Figure 2: People aged 20–64 with a Bachelor's degree or higher/Year 12 or equivalent qualification, by remoteness area, 2014–2023

This line chart shows the proportion of people aged 20–64 with a Bachelor’s degree or higher qualification or Year 12 equivalent qualification, by remoteness area. There was a higher proportion of people aged 20–64 living in Major Cities who have a Bachelor’s degree or higher qualification or Year 12 equivalent qualification compared with people living in Regional and Remote areas.

Source: ABS 2023b

Young people from rural and remote areas may be more likely to move to metropolitan areas to study and subsequently stay after completing their studies (Mackey 2019). The education levels of people living in rural and remote areas are also influenced by factors such as decreased study options, the skill and education requirements of available jobs and the earning capacity of jobs in these communities (Lamb and Glover 2014; Regional Education Expert Advisory Group 2019).

Employment and income

Employment underpins the economic output of a nation and enables people to support themselves, their families and their communities. Employment is also connected to physical and mental health and is a key factor in overall wellbeing (AIHW 2023f).

In general, people aged 15 and over living in metropolitan (greater capital city) areas are more likely to be employed than people living outside these areas (ABS 2023c). This may be due to fewer opportunities and access to work outside metropolitan areas and the smaller range of employment and career opportunities in these areas (ABS 2023c; NRHA 2013).

People living in rural and remote areas also generally have lower incomes but pay higher prices for goods and services (NRHA 2014). In 2019–20, Australians living outside capital cities had, on average, 15% less household income per week compared with those living in capital cities, and 22% less mean household net worth (ABS 2022a).

For more information, see Employment and unemployment and Income and income support.

Health risk factors

Health risk factors such as smoking, overweight and obesity, diet, high blood pressure, alcohol consumption and physical activity can influence health outcomes and the likelihood of developing disease or health disorders.

The AIHW National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) collects information on tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption and illicit drug use among the general population in Australia. Data for daily tobacco smoking from the latest NDSHS 2022–23 shows the proportion of people aged 14 and over who smoke daily increases with increasing remoteness, from 7% for those living in Major cities to 10.5% for Inner regional areas, 11.4% for Outer regional areas and 20.4% for those living in Remote and very remote areas (AIHW 2024a). Since 2019, these proportions have declined slightly in all remoteness areas, except in Remote and very remote areas (AIHW 2024a).

In 2022, based on self-reported data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ National Health Survey (NHS) and after adjusting for age, it was estimated that people living in Inner regional and Outer regional and remote areas were more likely to engage in risky behaviours, such as smoking and consuming alcohol at levels that put them at increased risk of alcohol-related diseases or injuries, compared with people living in Major cities (Figure 3; Table S3).

For more information, see Alcohol, tobacco & other drugs in Australia.

Figure 3: Prevalence of health risk factors, by remoteness area, 2022

This chart shows the prevalence of health risk factors including, current daily smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, inadequate fruit intake, inadequate vegetable intake, insufficient physical activity, overweight and obesity and high blood pressure by remoteness area. For most risk factors, prevalence was similar across all remoteness areas, except current daily smoking and excessive alcohol consumption which was higher outside of Major cities.

Notes:

- Proportions were age standardised to the 2001 Australian Standard Population.

- Excludes Very remote areas.

- Estimates for overweight or obese and high blood pressure are based on measured data while estimates for all other risk factors are based on self-reported data. For more information, see National Health Survey Methodology (ABS 2023f).

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2023e; Table S3.

Family, domestic and sexual violence

Family, domestic and sexual violence is a major health and welfare issue in Australia. The ABS 2021–22 Personal Safety Survey estimated that 8 million adults had been victims of physical and/or sexual violence from a partner since the age of 15 (ABS 2023g).

Women living outside Major cities were 1.5 times as likely to have experienced partner violence than women living in Major cities (23% compared with 15%). For men living outside of Major cities, 6.6% experienced partner violence compared with 5.9% of men living in Major cities (AIHW 2019).

For more information, see Family, domestic and sexual violence.

Health status and outcomes

Chronic conditions

Chronic conditions are long-lasting and have persistent effects throughout a person’s life. They are becoming increasingly common and are influenced by a wide variety of factors.

In 2022, based on self-reported data from the NHS and after adjusting for age, people living outside Major cities had higher rates of arthritis, and mental and behavioural conditions, while chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was higher in Outer regional and remote areas compared with Major cities (Figure 4; Table S4; ABS 2023e).

People living outside Major cities have lower usage of chronic disease management services, which can be due to availability of services or the health and age of the population within an area (AIHW 2022b).

For more information, see Chronic disease and Chronic conditions and multimorbidity.

Figure 4: Prevalence of selected chronic conditions, by remoteness areas, 2022

This chart shows the prevalence of chronic conditions including arthritis, asthma, back pain and problems, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, heart, stroke and vascular disease, mental and behavioural problems and osteoporosis by remoteness area. The prevalence of most chronic conditions was similar across remoteness areas but rates of arthritis and mental and behavioural conditions were higher outside of Major cities.

Notes:

- Proportions were age standardised to the 2001 Australian Standard Population.

- Excludes Very remote areas.

- Data are self-reported. For more information, see National Health Survey Methodology (ABS 2023f).

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2023e; Table S4.

Cancer

The age-standardised incidence rate of all cancers combined was highest in Inner regional and Outer regional areas in 2012–2016 (513 and 512 per 100,000 people, respectively), slightly lower in Major cities and Remote areas (both 487 cases per 100,000 people), and lowest in Very remote areas (422 cases per 100,000 people) (AIHW 2021b).

However, the incidence rate for all cancers combined for Very remote areas may be influenced by lower population screening participation rates, later detection of cancer and lower life expectancy due to death from other causes (AIHW 2021b; Fox and Boyce 2014). Very remote areas had the highest incidence rate for cervical cancer, liver cancer, cancer of unknown primary site, uterine cancer and head and neck cancers (including lip).

In the period 2012–2016, people living in Major cities had the highest 5-year observed survival for all cancers combined (63%) compared with 61% for all other areas, except for Very remote areas which had the lowest survival rate (55%) (AIHW 2021b).

For more information, see Cancer in Australia 2021 and Cancer.

Burden of disease

Burden of disease refers to the quantified impact of a disease or injury on a population, which captures overall health loss, that is, years of healthy life lost through premature death or living with ill health.

In 2018, after adjusting for age, the total burden of disease and injury in Australia increased with increasing remoteness (AIHW 2021a). The total burden was lowest in Major cities (174 DALY per 1000 population) rising to 200 and 204 for Inner and Outer regional areas, respectively, and 244 DALY per 1000 population in Remote and very remote areas. This pattern was mostly driven by fatal burden (years of life lost due to premature death).

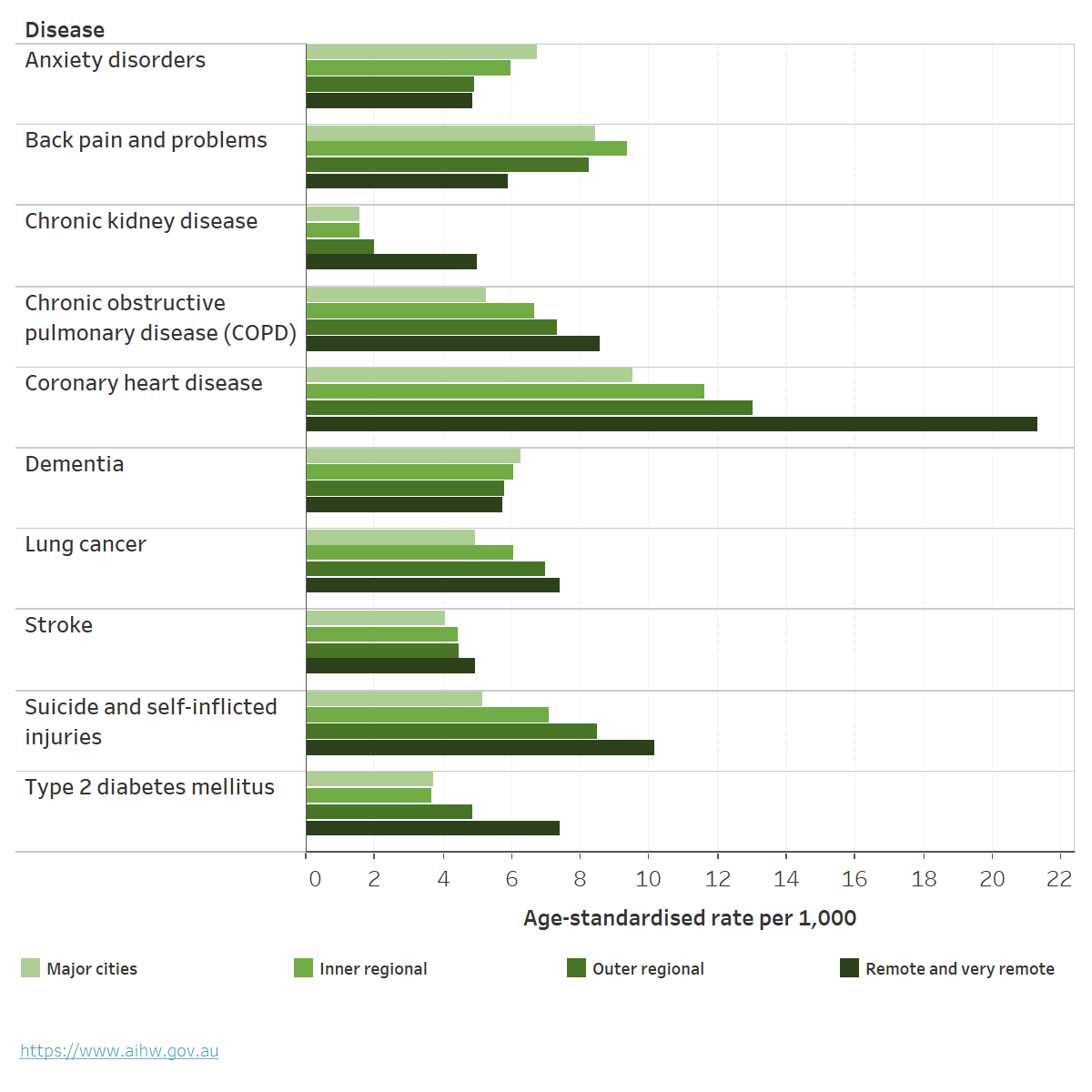

Figure 5 shows that for some chronic conditions, the burden of disease increased with increasing remoteness, such as coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, lung conditions and suicide and self-inflicted injuries. The burden of disease decreased with increasing remoteness for anxiety, back pain and dementia (Table S5; AIHW 2021a).

For more information, see Burden of disease.

Figure 5: Health burden for major diseases and injuries, by remoteness area, 2018

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW 2021a; Table S5.

Deaths

People living in rural and remote areas are more likely to die at a younger age than their counterparts in Major cities. They have higher mortality rates and higher rates of potentially avoidable deaths than those living in Major cities.

In 2021, age-standardised mortality rates increased as remoteness increased for males and females (Table 1; AIHW 2023h). Compared with all of Australia:

- People living in Inner or Outer regional areas had a mortality rate 1.1 times as high.

- People living in Remote areas had a mortality rate 1.2 times as high.

- People living in Very remote areas had a mortality rate 1.5 times as high.

- Males had a higher mortality rate than females in all remoteness areas.

For more information, see Deaths in Australia.

| Major cities | Inner regional | Outer regional | Remote | Very remote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at death (Males) | 80 | 79 | 77 | 73 | 67 |

| Age-standardised rate (deaths per 100,00) (Males) | 569 | 636 | 675 | 711 | 925 |

| Rate ratio (Males) | 0.95 | 1.06 | 1.13 | 1.19 | 1.55 |

| Median age at death (Females) | 85 | 84 | 83 | 79 | 69 |

| Age-standardised rate (deaths per 100,00) (Females) | 409 | 456 | 477 | 514 | 644 |

| Rate ratio (Females) | 0.96 | 1.07 | 1.12 | 1.20 | 1.51 |

Note: Rate ratios are calculated as the age-standardised rate for the geographic area of interest divided by the age-standardised rate for the reference group (all of Australia).

Source: AIHW 2023h.

Leading causes of death

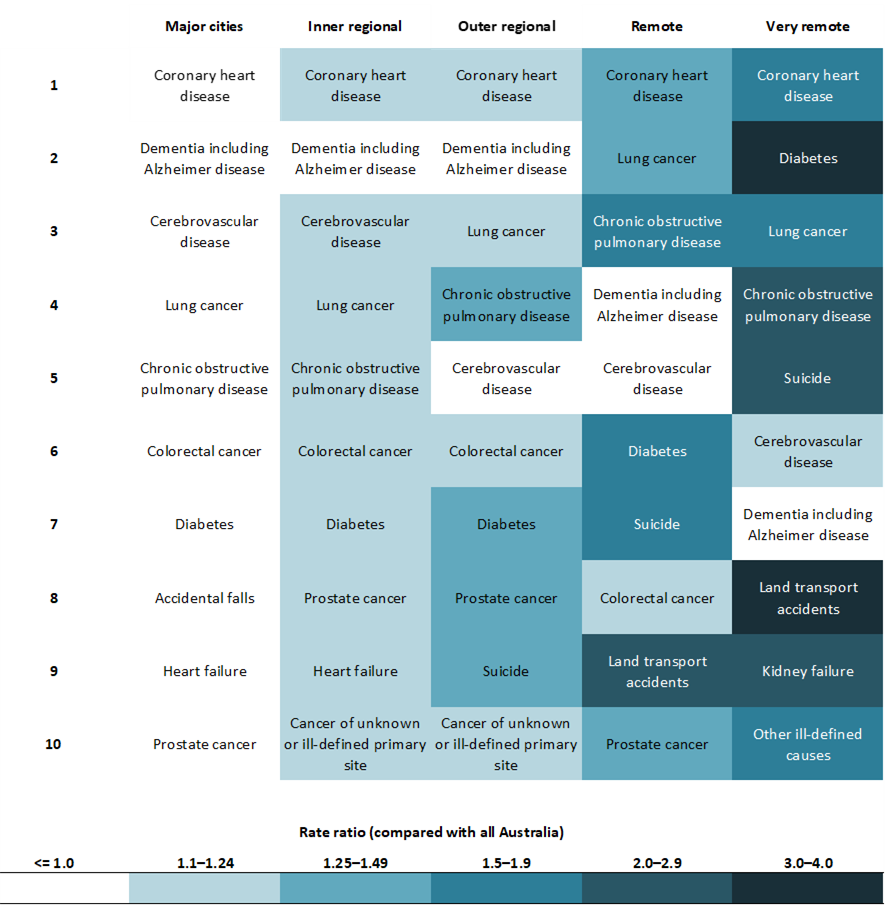

Between 2017–2021, when comparing mortality rates for Australia overall, the leading causes of death varied by remoteness area (Figure 6; AIHW 2023h).

- Coronary heart disease was the leading cause of death across all remoteness areas. Age-standardised rates were between 1.1 and 1.7 times higher outside of Major cities than for Australia overall.

- The top 7 causes of death were the same for Major cities, Inner regional and Outer regional areas.

- Land transport accidents were a leading cause of death in Remote and Very remote areas. The rate of dying due to land transport accidents was nearly 3 times as high for Remote areas and nearly 4 times as high for Very remote areas, compared with Australia overall (AIHW 2023h).

Figure 6: Leading cause of death by remoteness area, with comparison of mortality rates to Australia overall, 2017–2021

Notes

- Rates are age-standardised to the 2001 Australian standard population.

- Leading causes of death are listed in order of number of deaths in each remoteness area from 2017–2021.

- Boxes are coloured based on rate ratio comparing each region to Australia overall.

Source: AIHW 2023h; Table S4.

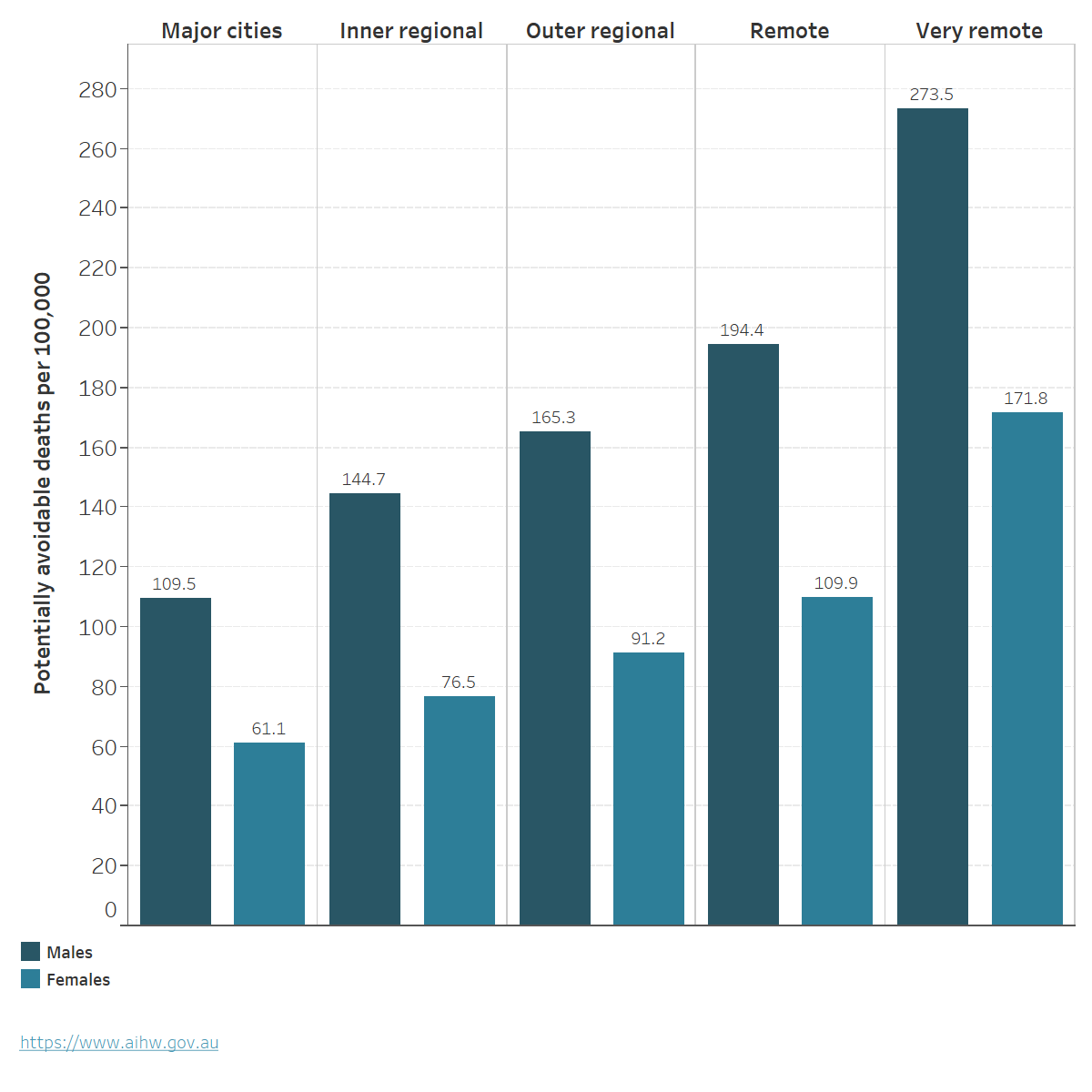

Potentially avoidable deaths

The rate of potentially avoidable deaths – deaths under the age of 75 from conditions that are potentially preventable through primary or hospital care, such as cancer screening and transport accidents – increased as remoteness increased. For information on examples and definitions of potentially avoidable deaths see Potentially avoidable deaths, 2022.

In 2021, 16% of all deaths in Australia were potentially avoidable (ABS 2023a). For males and females, the rate increased with increasing remoteness (Figure 7; Table S7). After adjusting for age and comparing with Major cities, the rates of potentially avoidable deaths were:

- 1.3 and 1.2 times as high in Inner regional areas for males and females

- 1.5 times as high in Outer regional areas for both males and females

- 2–3 times higher in Remote and Very remote areas (AIHW 2023h).

Figure 7: Potentially avoidable deaths by sex and remoteness area, 2021

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW 2023h; Table S7.

For more information, see Mortality Over Regions and Time (MORT) books

Life expectancy

Estimates of life expectancy at birth represent the average number of years that a newborn baby can expect to live, assuming current age-specific death rates are experienced through their lifetime. In 2020–2022, life expectancy at birth was lower for those living outside of metropolitan areas (greater capital city) (Table 2; ABS 2023d).

| Males | Females | Persons | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greater Sydney | 82.5 | 86.2 | 84.3 |

| Rest of NSW | 79.5 | 84.1 | 81.7 |

| Greater Melbourne | 82.3 | 86.0 | 84.1 |

| Rest of Vic. | 79.5 | 84.1 | 81.8 |

| Greater Brisbane | 81.2 | 85.3 | 83.2 |

| Rest of Qld | 80.3 | 84.8 | 82.5 |

| Greater Adelaide | 81.3 | 85.4 | 83.3 |

| Rest of SA | 80.1 | 84.3 | 82.2 |

| Greater Perth | 82.4 | 86.5 | 84.4 |

| Rest of WA | 79.4 | 83.7 | 81.5 |

| Greater Hobart | 80.6 | 85.1 | 82.8 |

| Rest of Tas. | 79.9 | 83.7 | 81.8 |

| Greater Darwin | 79.1 | 84.6 | 81.8 |

| Rest of NT | 71.6 | 75.8 | 73.7 |

Source: ABS 2023d.

Access to health care

People living in remote and very remote areas can face barriers to accessing and using health care, due to various challenges: geographic spread, low population density, limited infrastructure, and the higher costs of delivering rural and remote health care can limit the availability of services. The additional time and transportation costs to access health care services also means people in remote and very remote areas may delay access to preventive and primary health care and rely on hospital care to have their needs met (NRHA 2023).

Primary health care

Medicare claims data from 2022–23 show that the number of non-hospital non-referred attendances per person, such as general practitioner (GP) visits, were lowest in Remote communities (MM 6) and Very remote communities (MM 7) (4.2 and 3.4 per person respectively) (Table 3). However, bulk-billing rates were highest in Very remote communities (MM 7) (89%), lowest in Regional centres (MM 2) (75%) and similar across all other MMM areas (Table 3).

| Modified Monash (MM) category | Total number of GP Non-referred Attendances | Number of GP Non-referred Attendances per person | Number of Bulk-billed GP Non-referred Attendances | Per cent Bulk-billed GP Non-referred Attendances |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolitan areas (MM 1) | 122.1 million | 6.6 | 99 million | 80 |

| Regional centres (MM 2) | 14 million | 6.1 | 11 million | 75 |

| Large rural towns (MM 3) | 10.4 million | 6.3 | 8.2 million | 79 |

| Medium rural towns (MM 4) | 6.4 million | 6.4 | 5.1 million | 80 |

| Small rural towns (MM 5) | 11.1 million | 6.2 | 9 million | 81 |

| Remote communities (MM 6) | 1.2 million | 4.2 | 978,000 | 79 |

| Very remote communities (MM 7) | 706,000 | 3.4 | 628,000 | 89 |

Note: The number of GP non-referred attendances per person was calculated using the Estimated Resident Population at 30 June 2022.

Source: Department of Health and Aged Care 2023a.

Cancer Screening

Participation in bowel, breast and cervical cancer screening varies with remoteness:

- In 2020–2021, the bowel cancer screening participation rate for people aged 50–74 was highest for people living in Inner regional areas (43%) and lowest for people living in Very remote areas (25%) (AIHW 2023i).

- In 2020–2021, the breast cancer screening participation rate for females aged 50–74 was highest in Outer regional and Inner regional areas at 55% and 52%, respectively, and lowest for participants living in Very remote areas at 37% (AIHW 2023e).

- In 2018–2022, the cervical screening participation rate for females aged 25–74 years was similar but declined across remoteness areas, from 70% in Major cities to 65% in Outer regional areas and 60% in Very remote areas (AIHW 2023j).

For more information, see General practice, allied health and other primary care services and Cancer screening.

Health workforce

Australians living in rural, Remote and Very remote communities generally have poorer access to healthcare than people in Regional centres and Metropolitan areas, and may need to travel long distances or relocate to attend health services or receive specialised treatment (AIHW 2022a). The clinical FTE rate indicates the full-time equivalent number of health professionals working clinical hours relative to the population. In 2016–2021 the clinical FTE per 100,000 population was:

- highest in Metropolitan areas (MM 1) for many health professionals including specialists (all doctors other than GPs who require a referral from another doctor), occupational therapists, dentists, pharmacists, physiotherapists, psychologists.

- higher in Large rural towns (MM 3) compared with Metropolitan areas (MM 1) for optometrists, podiatrists and nurses and midwives.

- highest in Large rural towns (MM 3), Medium rural towns (MM 4), and Remote (MM 6) and Very remote (MM 7) communities for GPs.

- lowest in Small rural towns (MM 5), for all health professionals (including GPs) except for pharmacists. (Department of Health and Aged Care 2022) (Figure 8; Table S8).

Although the FTE rate for GPs increases with increasing remoteness, care should be taken in interpreting the data, as work arrangements in these areas have the potential to be more complicated (NRHA 2019). For example, there may be poor differentiation between general practice for on-call hours, activity for procedures and hospital work for GPs working in rural and remote areas, which affects the accuracy of statistics on GP supply and distribution (Walters et al. 2017).

For more information, see Health workforce.

Figure 8: Employed health professionals, clinical full-time equivalent (FTE) rate, by Modified Monash (MM) category

This chart shows the clinical FTE rate of health professionals including dentists, general practitioners, nurses and midwives, occupational therapists, optometrists, pharmacists, physiotherapists, podiatrists, psychologists and specialists by area of remoteness and year. In 2016–2021, the clinical FTE rate of most health professionals was highest in Metropolitan Areas (MM1) except optometrists, podiatrists, nurses and midwives and GPs. The clinical FTE rate for all health professionals was lowest in Small rural towns (MM5), except for pharmacists.

Notes:

- Calculations are based on the FTE clinical rate and report health practitioners working in clinical practice using the Estimated Resident Population of that year.

- FTE clinical rates are equal to the FTE number per 100,000 population, which is based on total weekly hours worked. For medical practitioners, the standard working week is 40 hours and for all other health practitioners it is 38 hours.

- Modified Monash (MM) category is derived from Modified Monash (MM) category of main job where available; otherwise, Modified Monash (MM) category of principal practice is used as a proxy.

- Numbers represent not only those in the labour force, but those employed and working in their registered profession.

Sources: ABS 2022a; Department of Health 2022a; Table S8.

Hospitalisations

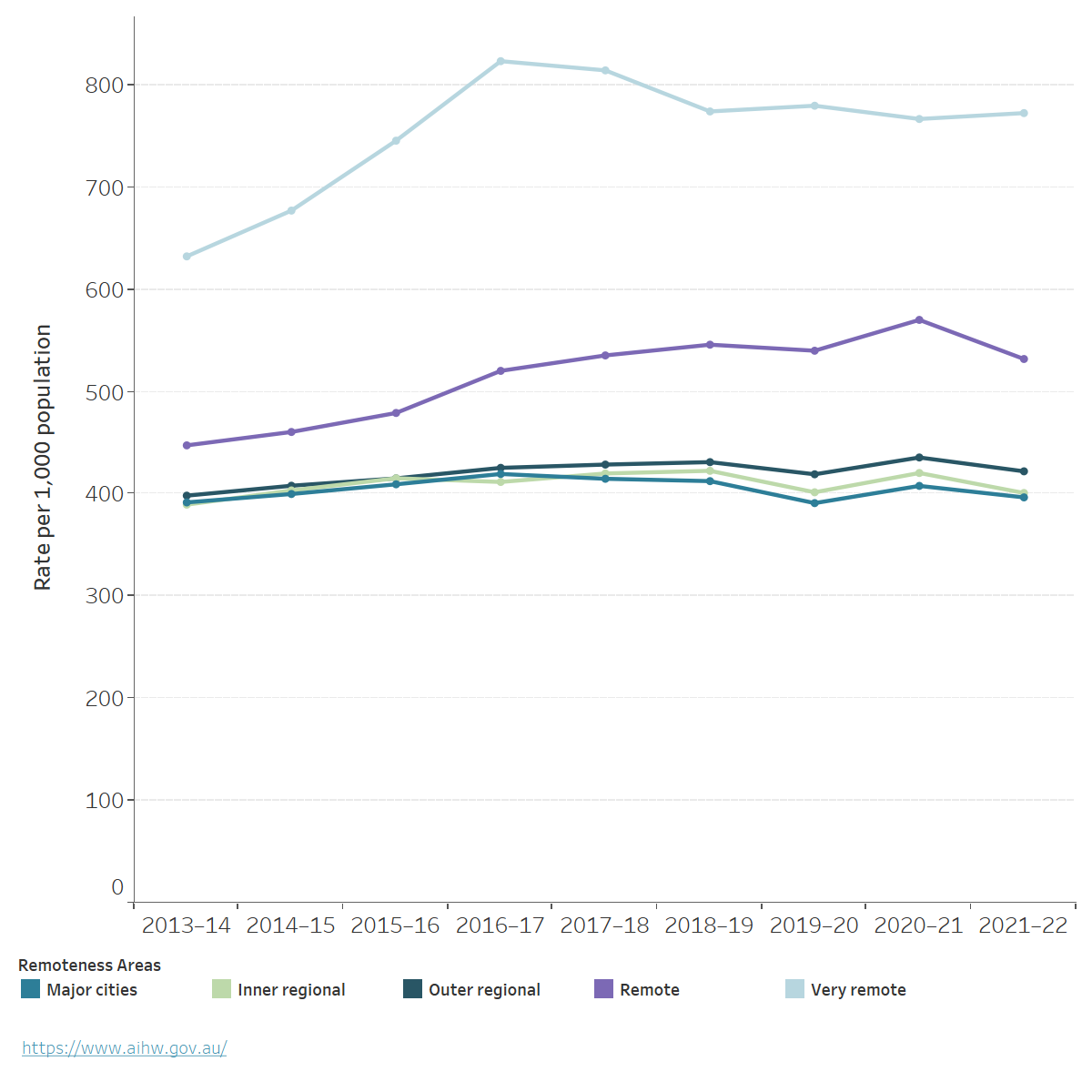

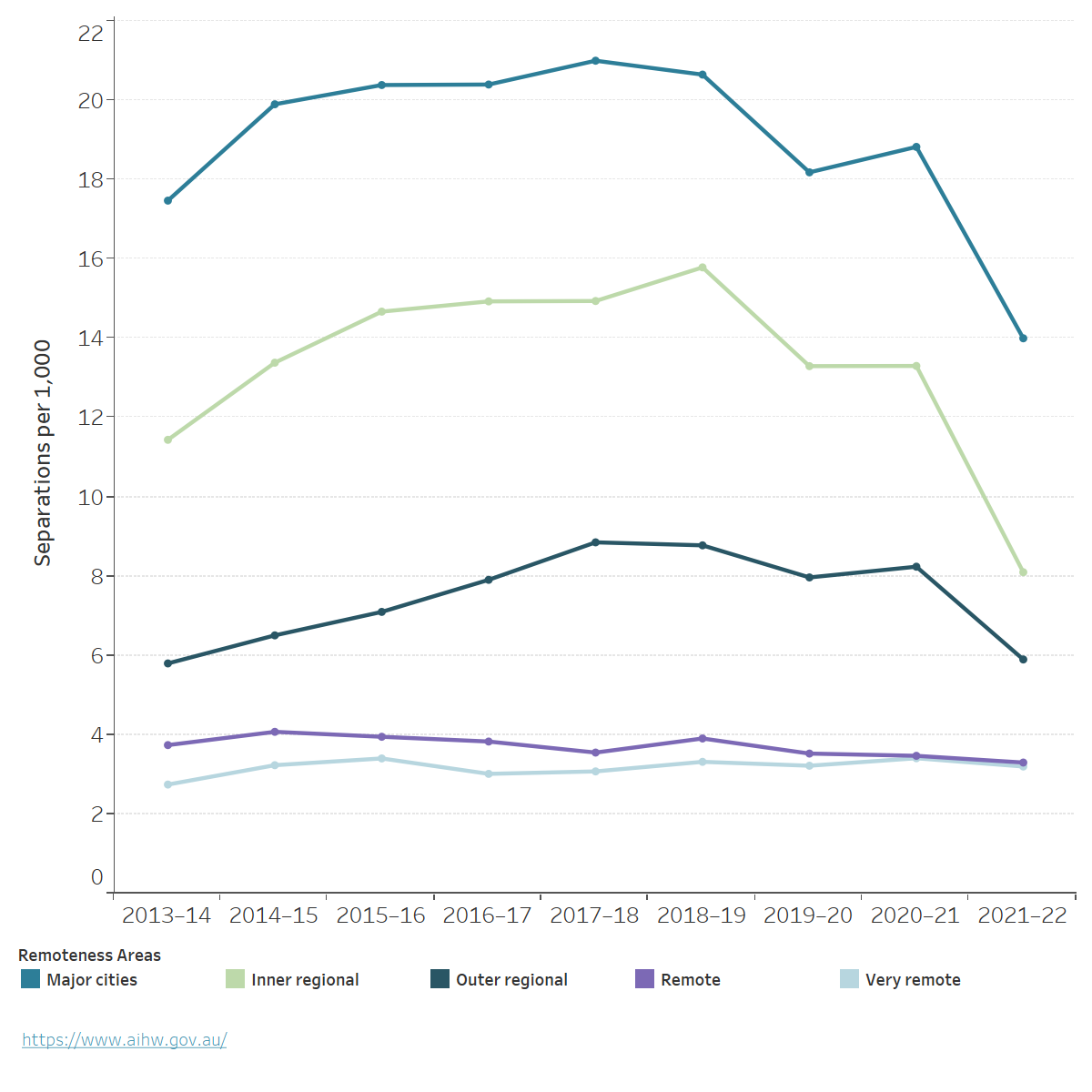

In 2021–22, the number of hospitalisations per 1,000 people was similar for Major cities and regional areas (AIHW 2023b). People living in Very remote areas were hospitalised at almost twice the rate as people living in Major cities and those in Remote areas at 1.3 times the rate, with no improvement since 2013–14 (Figure 9; AIHW 2023b).

Figure 9: Hospitalisations, by remoteness area of usual residence, public and private hospitals, 2013–14 to 2021–22

Notes:

- Separations per 1,000 population are reported as directly age-standardised rates based on Australian population as at 30 June of the year of interest, the Australian population as at 30 June 2001 was used as the reference population.

- Remoteness of area of usual residence is based on the patient's area of residence (provided at Statistical Area level 2)

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW 2023b; Table S9.

Overall, there was a decrease in the rate of all hospitalisations in 2021–22 across all remoteness areas except for Very remote areas, which could be due to the impact of COVID-19 on provision of healthcare services and reduced flow of patients seeking in-hospital care (AIHW 2023a).

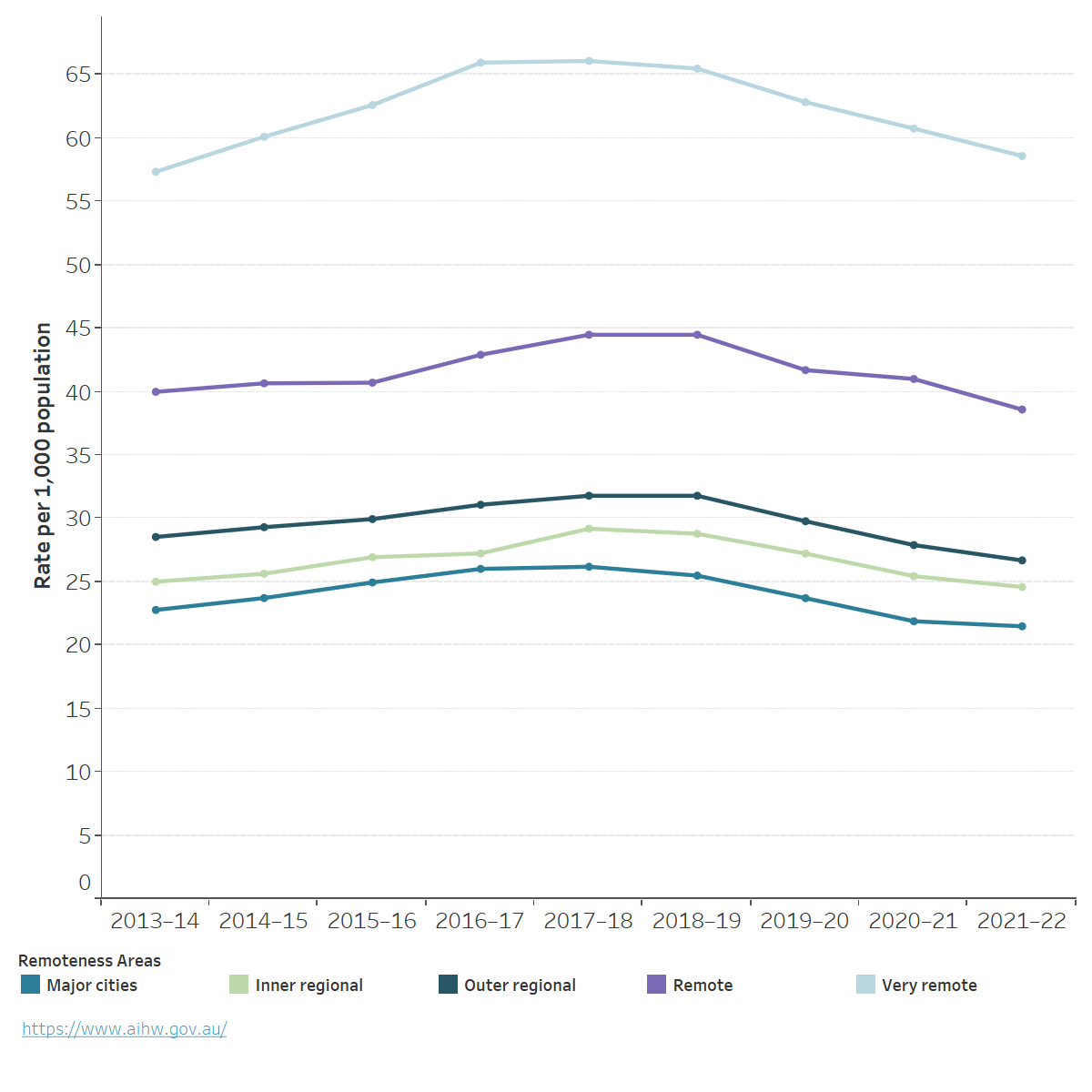

People in Major cities have higher rates of rehabilitation care hospitalisations compared with people living in other remoteness areas (Figure 10; Table S10; AIHW 2023c). In 2021-22, there were 14 hospitalisations per 1,000 population living in Major cities compared with 8 for Inner regional areas, 6 for Outer regional areas, 3 for both Remote and Very remote areas. In part, this may reflect the distribution of private hospitals across remoteness areas, as private hospitals accounted for 81% of rehabilitation care separations (AIHW 2023c).

For more information, see Hospitals.

Figure 10: Hospitalisations for rehabilitation care, by remoteness area of usual residence, public and private hospitals, 2013–14 to 2021–22

Notes:

1. Separations per 1,000 population are reported as directly age-standardised rates based on the Australian population as at 30 June of the year of interest. The Australian population as at 30 June 2001 was used as the reference population.

2. Separations for which care type was reported as Rehabilitation.

3. Remoteness of area of usual residence is based on patient's area of usual residence (provided as Statistical Area level 2).

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW 2023c; Table S10.

Potentially preventable hospitalisations

Potentially preventable hospitalisations (PPH) are for conditions where hospitalisation could have potentially been prevented through the provision of appropriate individualised preventative health interventions and early disease management, usually delivered in primary care and community-based settings. The rate of PPH increases with remoteness and is highest in Very remote and Remote areas (Figure 11; Table S11; AIHW 2023d).

When compared with Major cities, the rate of PPH in 2021–22 was:

- slightly higher in Inner regional and Outer regional areas (1.1 and 1.2 times as high, respectively)

- 2–3 times as high for people living in Remote and Very remote areas (AIHW 2023d).

Figure 11: Potentially preventable hospitalisations, by remoteness area of usual residence, all hospitals, 2013–14 to 2021–22

Notes

- Separations per 1,000 population are reported as directly age-standardised rates based on the Australian population as at 30 June of the year of interest. The Australian population as at 30 June 2001 was used as the reference population.

- Remoteness of area of usual residence is based on the patient's area of residence (provided as Statistical Area level 2 for most jurisdictions)

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW 2020, AIHW 2023d, Table S11.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on rural and remote health please see:

- Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2018

- Mortality Over Regions and Time (MORT) books

- Admitted patients

- Cancer statistics for small geographic areas

- National Rural Health Alliance

- Glossary

For more on this topic, visit Rural and remote Australians.

ABS (2021) Remoteness structure, ABS website, accessed 10 January 2022.

ABS (2022a) Household Income and Wealth, Australia, ABS website, accessed 25 January 2023.

ABS (2022b) Regional population by age and sex. Obtained from the ABS via data request on 28/09/2022, accessed 30 March 2023.

ABS (2023a) Causes of death, Australia, ABS website, accessed 12 March 2024.

ABS (2023b) Education and work, Australia, ABS website, accessed 21 December 2023

ABS (2023c) Labour force, Australia, Detailed, ABS website, accessed 20 December 2023.

ABS (2023d) Life expectancy, ABS website, accessed 21 December 2023.

ABS (2023e) Microdata and Tablebuilder: National Health Survey, AIHW analysis of detailed microdata, accessed 23 March 2024.

ABS (2023f) National Health Survey methodology, ABS website, accessed 23 March 2024.

ABS (2023g) Personal Safety, Australia, 2021–22, ABS website, accessed 29 February 2024.

ABS (2023h) Regional population by age and sex. Obtained from the ABS via data request on 29/09/2023, accessed 8 January 2024.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2019) Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 20 March 2022.

AIHW (2020) Disparities in potentially preventable hospitalisations across Australia: exploring the data [data set], aihw.gov.au, accessed 25 January 2023.

AIHW (2021a) Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2018, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 29 April 2022.

AIHW (2021b) Cancer in Australia 2021, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 20 March 2022.

AIHW (2022a) Health workforce, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 3 April 2023.

AIHW (2022b) Use of chronic disease management and allied health Medicare services, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 13 June 2023.

AIHW (2023a) Admitted patient activity, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 2 June 2023.

AIHW (2023b) Admitted patient care 3: Who used these admitted patient services? [data set], aihw.gov.au, accessed 31 May 2023.

AIHW (2023c) Admitted patient care 5: What services were provided? [data set], aihw.gov.au, accessed 31 May 2023.

AIHW (2023d) Admitted patient care 8: Safety and quality of health systems [data set], aihw.gov.au, accessed 31 May 2023.

AIHW (2023e) BreastScreen Australia monitoring report 2023, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 20 December 2023.

AIHW (2023f) Employment and unemployment, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 1 March 2024.

AIHW (2023g) Higher education, vocational education and training, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 1 March 2024.

AIHW (2023h) Mortality Over Regions and Time (MORT) books, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 11 July 2023.

AIHW (2023i) National Bowel Cancer Screening Program monitoring report 2023, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 20 December 2023.

AIHW (2023j) National Cervical Screening Program monitoring report 2023, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 20 December 2023.

AIHW (2023k) Profile of First Nations people, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 20 December 2023.

AIHW (2024a) National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–23, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 29 February 2024.

Department of Health (2021) Physical activity and exercise guidelines for all Australians, Department of Health, accessed 28 March 2024.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2022) Health workforce data tool [data set], health.gov.au, accessed 10 February 2023.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2023a) Medicare annual statistics – Modified Monash Model locations (2009-10 to 2022-23) [data set], health.gov.au, accessed 16 February 2024.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2023b) Modified Monash Model, Department of Health and Aged Care, Australian Government, accessed 29 February 2024.

Fox P and Boyce A (2014) ‘Cancer health inequality persists in regional and remote Australia’, Medical Journal of Australia, 201(8):445–446, doi:10.5694/mja14.01217.

Lamb S and Glover S (2014) Educational disadvantage and regional and rural schools, Victoria University, accessed 19 April 2022.

Mackey W (2019) More regional Australians are moving to the city to study. Few return when they’ve finished, Grattan Institute, accessed 19 April 2022.

NHRMC (National Health and Medical Research Council) (2013) Australian Dietary Guidelines, NHRMC website, accessed 28 March 2024.

NHRMC (2020) The Australian Alcohol Guidelines, NHRMC website, accessed 28 March 2024.

NRHA (National Rural Health Alliance) (2013) A snapshot of poverty in rural and regional Australia, NRHA, accessed 19 April 2022.

NRHA (2014) Income inequality experienced by the people of rural and remote Australia, NRHA, accessed 19 April 2022.

NRHA (2019) Medical practitioners in rural, regional and remote Australia, NRHA, accessed 5 March 2024.

NRHA (2023) Evidence base for additional investment in rural health in Australia, NRHA, accessed 18 March 2024.

Regional Education Expert Advisory Group (2019) National regional, rural and remote education strategy: final report, Department of Education, Australian Government, accessed 20 February 2022.

Walters L, McGrail MR, Carson DB, O’Sullivan BG, Russell DJ, Strasser RP, Hays RB and Kamien M (2017) ‘Where to next for rural general practice policy and research in Australia?’, Medical Journal of Australia, 207(2):56–58, doi:10.5694/mja17.00216.

This page was last updated 30 April 2024. All information on this page is the most recent available, as at that date.